- PHOTOS:

- Dec 16, 2008 - May 21, 2009

- Mar 17, 2008 - Dec 15, 2008

- Nov 01, 2007 - Mar 16, 2008

- Our SC35 Sailboat: PRUDENCE

- SELECTED BLOGS

- Jan'05: The Idea

- May'05: First Cruise - Belize

- Aug'05: Buying Ashiya

- Oct'05: School in St. Vincent

- Nov'05: Ocracoke on Ashiya

- Jul'06: Long Trip on Ashiya

- Oct'06: Prudence Comes Home

- Nov'07: First Night Offshore

- Nov'07: Offshore Take Two

- Nov'07: Gulf Stream Crossing

- Dec'07: Green Turtle Cay

- Dec'07: Lynyard Cay

- Dec'07: Warderick Wells Cay

- Jan'08: George Town

- Jan'08: Life without a Fridge

- Jan'08: Mayaguana Island

- Jan'08: Turks & Caicos

- Jan'08: Dominican Republic

- Jan'08: Down the Waterfalls

- Feb'08: Puerto Rico

- Feb'08: Starter Troubles

- Feb'08: Vieques

- Mar'08: Finally Sailing Again

- Mar'08: Trip So Far

- Mar'08: Hiking Culebra

- Mar'08: Kayak & Snorkel I

- Mar'08: Teak and Waterspouts

- Mar'08: Kayak & Snorkel II

- Mar'08: Bottom Cleaning

- Apr'08: Culebra Social Life

- Apr'08: Culebra Routine

- Apr'08: Culebra Beaches

- Apr'08: Culebrita

- Jun'08: Kayak & Snorkel III

- Jun'08: Kayak & Snorkel IV

- Jun'08: Manta Ray

- Jun'08: Sea Turtles

- Jul'08: Cost of Cruising

- Jul'08: Busy Week in Culebra

- Jul'08: Getting to Land

- Jul'08: Leatherback Boil

- Jul'08: Fish and Volcano Dust

- Aug'08: Teaching Algebra

- Sep'08: Culebra Card Club

- Oct'08: Kayak & Snorkel V

- Oct'08: Prep for Hurricane

- Oct'08: Hurricane Omar

- Oct'08: Fish and Sea Glass

- Oct'08: Waterspouts

- Dec'08: Hurricane Season Ends

- Dec'08: Culebra to St. Martin

- Jan'09: Antigua Part 1

- Feb'09: The Saints

- Feb'09: Visiting Dominica

- Mar'09: Antigua Part 2

- Apr'09: Antigua to Bermuda

- May'09: Bermuda to Norfolk

- FULL LIST of Blog Entries

15 July 2009

14 July 2009

15 June 2009

14 June 2009 | Annapolis, MD

13 June 2009

12 June 2009

11 June 2009

10 June 2009 | Little Creek Marina, Norfolk, VA, USA

04 June 2009 | Little Creek Marina, Norfolk, VA, USA

31 May 2009 | Little Creek Marina, Norfolk, VA, USA

29 May 2009 | Little Creek Marina, Norfolk, VA, USA

26 May 2009 | Little Creek Marina, Norfolk, VA, USA

25 May 2009 | Little Creek Marina, Norfolk, VA, USA

13 May 2009 | through 21-May-2009

13 May 2009 | through 21-May-2009

12 May 2009 | St George's Town, Bermuda

11 May 2009 | St George's Town, Bermuda

07 May 2009 | St George's Town, Bermuda

04 May 2009 | St George's Town, Bermuda

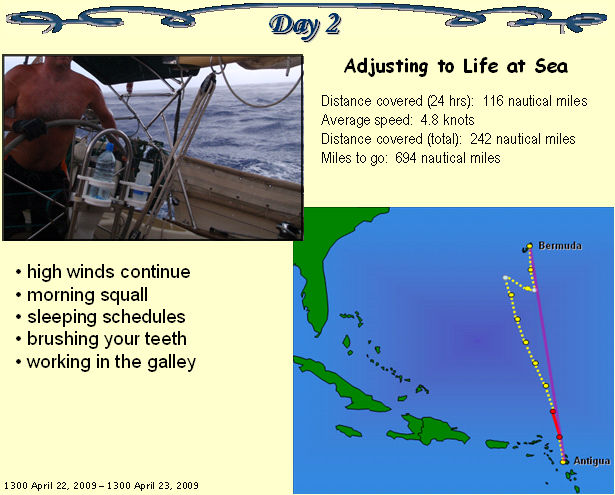

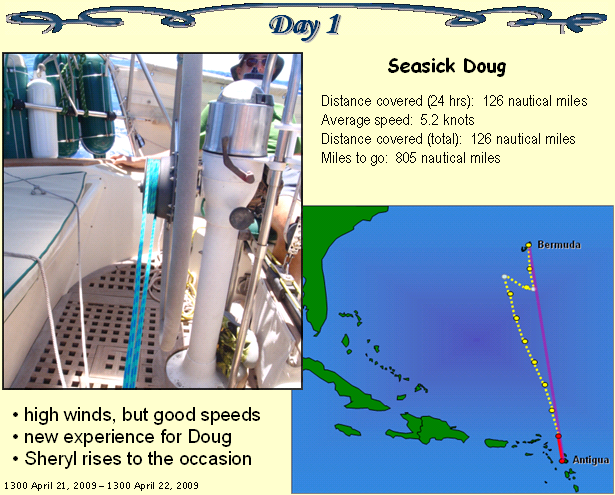

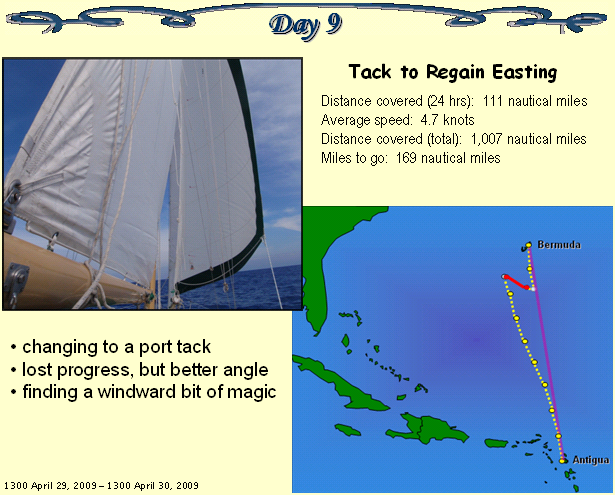

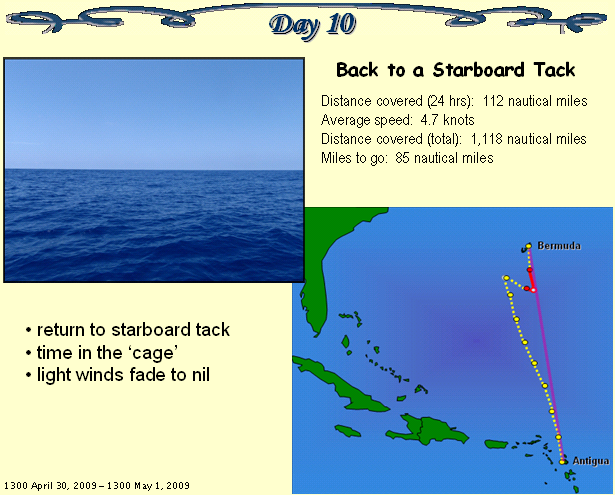

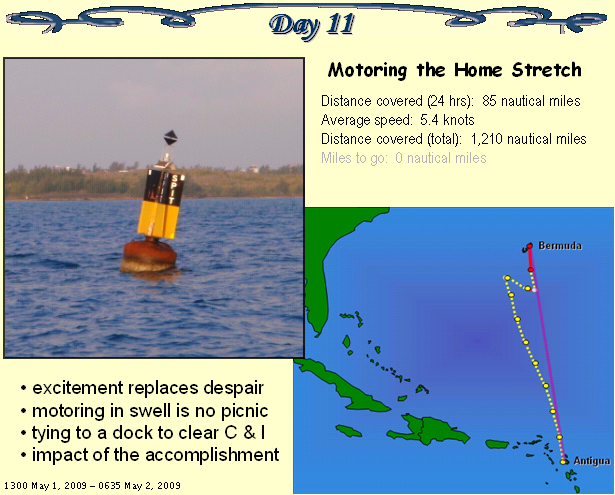

21 April 2009 | through 02-May-2009

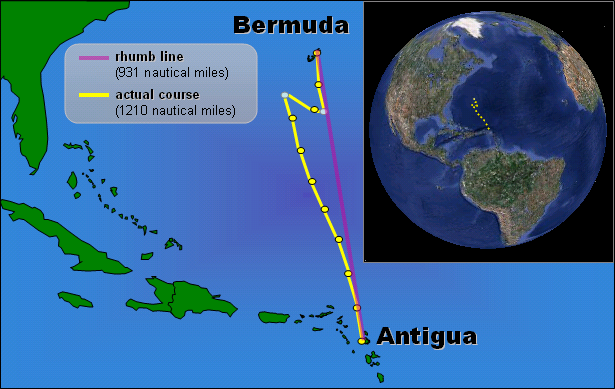

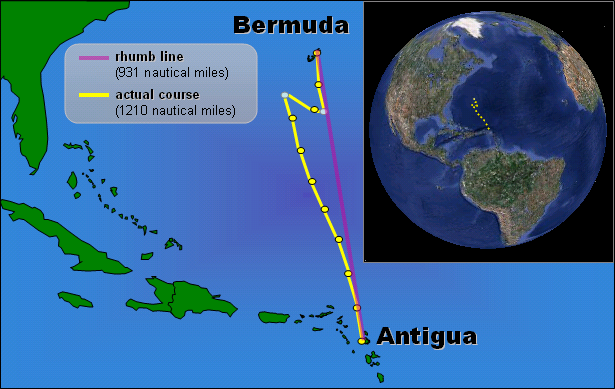

Passage from Antigua to Bermuda

21 April 2009 | through 02-May-2009

Prologue: Eleven days at sea. When we asked ourselves, 'Why go to Bermuda?', the answer was ... 'For the experience of the journey'. The destination, visiting Bermuda, was certainly secondary.

Sheryl, in particular, felt that our cruising experience was lacking in one regard ... a long offshore trip. Our longest to date had been just under three days. All of the cruising couples we have spoken to who are experienced offshore sailors say that everything changes after day three. It was our time to develop our own opinion on the matter.

During some more arduous portions of the trip, I rhetorically asked Sheryl, "Is this the experience you were looking for?" However, shortly after completing this journey, I asked the same question with less sarcasm in my voice. Her smile in return said it all.

Synopsis: We have just completed the passage from Antigua to Bermuda. It took 11 days and added over 1,200 nautical miles to our sailing bailiwick. We experienced everything ranging from big winds pushing us through big seas to struggling to make the boat move in calm conditions. In addition, a conniving current took its usual toll on our overall progress. Stuff broke, but we managed to effect repairs and continue onward. The biggest physical challenges were sleep deprivation and living in a cockeyed home with extreme increases in gravity occurring at random intervals. The biggest mental challenge was the extreme isolation, knowing that assistance on any matter from mechanical to medical was completely and utterly absent.

Cast: Aboard our 35-foot Southern Cross sailboat, Prudence, the following persons and machines contributed to a successful passage:

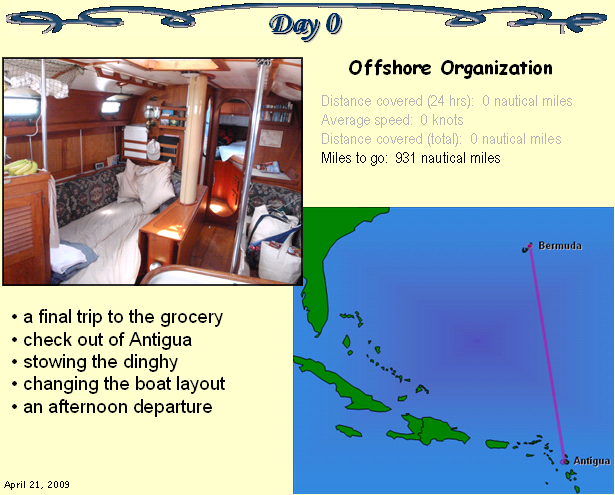

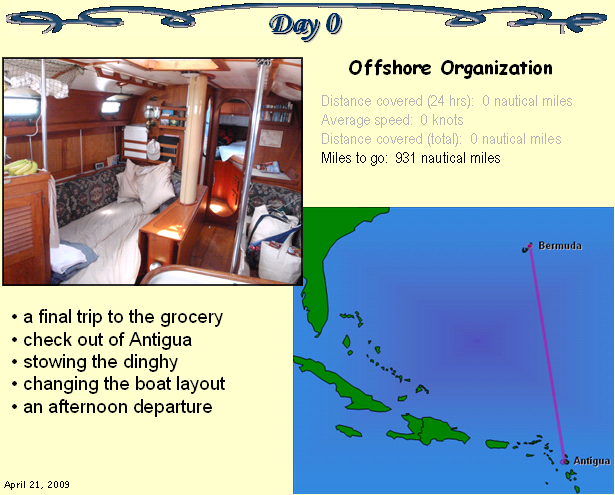

We woke on Tuesday, April 21st, our departure date, brimming with anticipation. Unlike a lot of our shorter journeys, there was no driver to make a first light departure, so we were able to enjoy breakfast before seeking resolution to the remaining items on our pre-departure checklist. The cereal had to compete with an active bunch of butterflies for space in my stomach. Getting busy getting ready was to be the best treatment for my mounting anxieties.

While Sheryl took our dinghy, Patience, to town to made a final trip to the grocery store to get fresh eggs and bread and then to check out with Customs and Immigration, I reorganized the cockpit locker contents and stowed other items in more offshore-friendly locations. Our v-berth is unsuitable for sleeping while underway. The motion of the boat that far forward can be likened to a ride on the Vomit Comit. Therefore, the space can be used for storage. Certain items can be laid out on top of the berth to be grabbed easily rather than having to be dug out of a locker while underway.

Upon Sheryl's return, we hauled the engine from the dinghy and the dinghy from the water. While I deflated and disassembled the dinghy, Sheryl re-organized some items in the cabin. Our appetites generally suffer while underway, and the degree of difficulty in food preparation increases exponentially. Consequently, we are doing all we can to make access to food simple. Quick cooking one-dish meals are planned and snacks will be readily available in a hammock hanging above the starboard settee.

Because the v-berth is such a bucking bronco when underway, we have packed our clothing in bags and secured them behind a lee cloth on the starboard settee. Digging out that sweatshirt I haven't worn in over a year and a half might have been a pain to accomplish in a couple of days. Now it will not require an hour in the forward area of the boat. That job is already done.

On previous passages, our inflatable kayaks were stored between the table and the port settee, making a narrow place in which to wedge oneself into a somewhat cozy sleeping berth. Because we sold the kayaks, and because this was to be such a long passage, we decided to open the berth into its sleeping orientation. Because most of the trip would be on a starboard tack, this should provide a spacious and comfortable sleeping space on the low side of the boat for the off-watch person. We dubbed this area 'The Nest.'

We double and triple checked everything on deck and below. Items needed to be secure yet accessible when needed. We took down the Antigua courtesy flag and started the engine. By 1PM, we had the anchor off the bottom of Mosquito Cove and were underway.

Since sailing our boat will now be a 24-hours a day - seven days a week operation, we have decided that each new day will start at 1300 AST. Therefore, please be aware that each 'day' described below starts and ends at the mid-day hour of 1300 hours.

The engine was turned off less than 1 hour after it was started. Shortly after that, SUE was engaged to steer the boat. Last week, Sheryl took the time to replace all of the steering lines on SUE with new rope. The new line was working well and would eventually pay great dividends toward our individual energy levels over the days to come.

Although the anxiety level was high on the days leading up to departure, I feel like a weight has been lifted off of my shoulders. Now, the decision point has passed. We are committed to this endeavor. That is not to say that I am no longer anxious, a certain baseline of anxiousness accompanies me anytime we are underway. I simply feel ready to take on this challenge and face my fears.

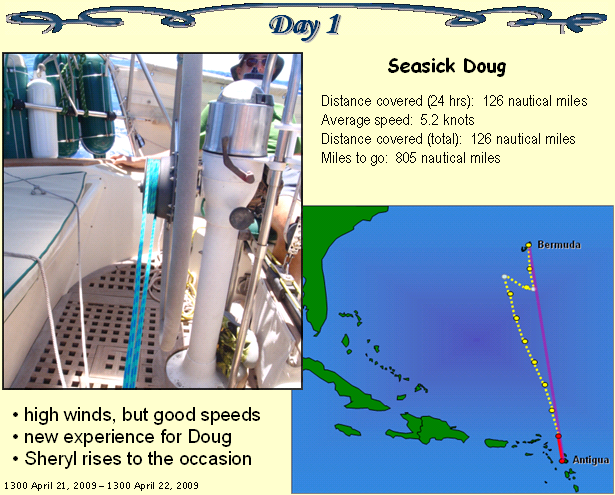

In our past experiences with extended passages, the weather forecast is generally reasonably accurate for the first day or two. We elected to depart at a time where the trades were going to be blowing pretty strong (15-20 knots). We knew, however, that the wind direction would put us on a beam reach and we could make good speeds even with sails reefed (which we prefer to do at night). Getting a couple of days of good progress in the beginning would be important to our morale and would get us totally clear of these pesky islands. The idea here is that lots of sea room will allow us to take any orientation we needed to be comfortable in the event of really, really strong winds and high seas.

Because we chose to depart in somewhat boisterous conditions, the motion of the boat was fairly drastic. Sheryl has suffered from seasickness ever since our first extended offshore passage, back in November 2007. Since then, she has found medication and techniques to manage this malady. It is not entirely eradicated, but it is subdued enough to allow her to function. When these moderated symptoms hit her on this trip, I could tell. She bravely shrugged them off, stating, "I just hope that what everyone says about seasickness going away after a few days is true. I look forward to being able to spend time below or even read a book later this week."

I have never suffered from sea sickness. I do get the occasional queasy feeling when trying to do chartwork below in rough conditions, but never the full-blown symptoms I have observed in others. This time it got to me. As the morning sun rose and we headed toward the completion of our first 24 hours underway, I found that my breakfast was not settling well. I will spare you the graphic details and simply state that I was under the weather for a spell.

Sheryl, still suffering from her own sea-induced sensations, rose to the occasion and took care of me ... selflessly granting me a little extra sleep time, going below so that I would not have to, and gently encouraging me to eat (even if only to nibble on a few saltines). That, my friends, is true love.

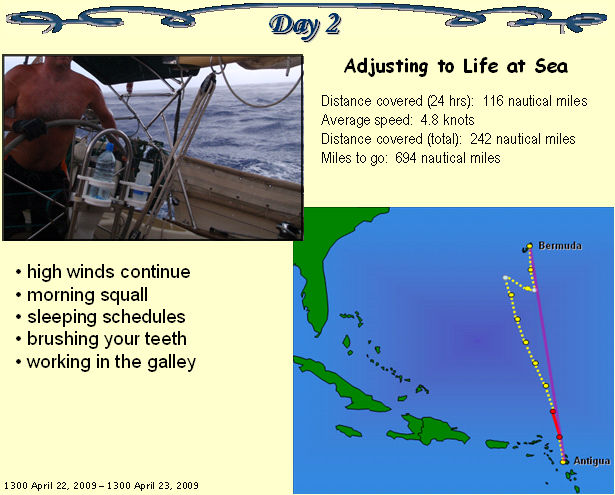

The morning hours brought us a squall. Each squall has its own characteristics, but when we spot these things on the horizon, we immediately think of increasing winds. In actuality, this squall we passed through brought both extremes. First, the winds died. We drifted in 0 knots of wind. Because SUE doesn't know what to do with zero knots of wind, I took the helm. Then, just before the rain started, the winds picked up to 20 knots in an instant. Water soon joined the onslaught from the cloud above and visibility dove down to near nothing. The situation is not fun, and I simply hope that we never meet another boat while sailing through a squall.

Fortunately, squalls usually pass after only a few minutes, and this one was no exception. As we passed out through another section of diminished winds, we watched it move on. Eventually, the winds built back to normal levels and the sun returned to dry out our well-soaked cockpit.

Both Sheryl and I are feeling better today, the effects of sea sickness are waning. We are beginning to acclimate to life underway. It is a matter of accepting the circumstances, though, not necessarily one of enjoying them.

First and foremost, let's talk about sleep. On our previous passages, this was always our biggest struggle, for me especially. I simply could not sleep well when underway. After one or two nights at sea, I would arrive at our destination thoroughly exhausted. When I extrapolated this to the length of our current passage, I worried that I might simply parish from the fatigue.

As it turns out, though, I fell into a pattern of sleeping fairly early into the voyage. Perhaps it was knowing that I just had to do it. Or, maybe it was because sleep was the only way to escape the sensations of seasickness. Regardless, it was good.

Unfortunately, one never quite gets enough sleep while underway. With only two of us having to cover a 24-hour watch, there is only so much time for uninterrupted sleep. Although we have tried other schedules, we decided that for this trip we would work 3-hour shifts. We start shiftwork at 1600 hours (4PM) and alternate watches every three hours until 1000 (10AM). Each day we switch shifts, one day Sheryl will start at 4PM and the next I will. This gives us both an opportunity to enjoy events like sunsets and sunrises. During the daylight hours from 10AM-4PM, we operate under a slightly less regimented plan where we simply take our even share of those hours, based on the day's whim.

Considering that schedule, what it boils down to is this. For two people who have grown quite accustomed to a full night's sleep (without even the interruption of a morning alarm clock), we are getting less than 3 hours of continuous sleep at any one interval. It is like hearing a snippet of a song you really, really like. You long to hear the whole thing. We crave a continuous, uninterrupted, night's sleep. Unfortunately, it will be a long time yet before we can satiate that craving.

In this world of modified schedules, other things change. You don't realize how much of your daily routine revolves around subtle cues, like going to sleep at night and waking up in the morning. Those, for me, are triggers to brush my teeth. Currently, I am brushing my teeth at least six times a day.

Meals also lack the normal temporal regularity. I find that I eat underway only when I am really, really hungry. Part of this is because anxiety affects me as an appetite suppressant, and as stated previously: I am always anxious while underway. The other part is that making food is a real chore. Our galley has several wonderful features which help, but it is still a chore.

Imagine yourself standing in the galley above. You are hungry and you want to make something as simple as a bowl of cereal and a cup of coffee. The coffee is instant, so first you need to start some water heating in the kettle. Because the boat is heeled to the port side and bouncing over waves, you have to hang on to the stainless steel bar in front of the stove with one hand to keep from being tossed over into the navigation station (this happened once to Sheryl, and it was not fun). You must hold on at ALL TIMES, otherwise you will fall.

So you pick up the kettle with one hand, but do not have a free hand to turn the faucet. Never fear, we have a solution. You set the kettle back down and loop the rope hanging in front of the stove behind your back and clip it to the other side. With the rope holding your weight, you have both hands free. You pick up the kettle again and turn the water faucet. Unfortunately, only a trickle comes out because you have forgotten to turn on the water pump (we leave it off in case a leak develops in the system and all our fresh water gets pumped into the bilge).

So, you set the kettle back down. Unhook the rope while holding on with the other hand and ease yourself over to the panel above the navigation station. Once the switch for the water pump is turned on, you climb back up to the galley and secure yourself once again with the rope. Now you can finally fill that kettle with water.

O.K., time to light the stove. But wait, the LP switch is off (as a safety precaution, a switch controls a solenoid which shuts off the flow of propane gas into the boat; again, we keep this off when not in use in case a leak develops in the system). So, you are going to have to go back to the panel in the navigation station.

The stove tilts from port to starboard on what is called a gimbal, preventing the heeling of the boat from effecting your cooking; however, you are also experiencing some occasional pitching motion. To be safe, you lock the kettle full of water on the stove with the use of fiddles. These little bars sit on each side of the pot to prevent fore/aft motion and lock to the stove with the use of a thumb screw.

Once the kettle is secure, you repeat the dance down to the nav station and flip the LP switch. While you are there, you also turn off the water pump (just out of habit), then back up to the galley and re-attach the rope. Now light a burner, loosen the fiddle, move the kettle to the burner, and tighten another fiddle. Whew, all that just to boil water.

Now you need to round up the supplies. Cereal and instant coffee are stored in the well set into our table. So you unhook the rope again and use handholds to work your way over to the table. You pop the lid on the well and take out what you need. Meanwhile, the lid slides sideways onto the sleeping berth. You'll be putting these things away later, so you just leave it there.

With a box of cereal and a jar of coffee crystals cradled awkwardly in one arm, you handhold your way back to the galley and place the items on the counter. You have to lie them down so that the lip on the counter will hold them in place, otherwise they will topple over and tumble into the nav station.

You secure yourself with the rope and get out a bowl and spoon, placing them on the counter. We have a couple of silicone hot pads which stick to the counter pretty well. Placing the bowl on one keeps it from sliding down upon the box of cereal and jar of coffee. You put the spoon in the bowl. You also get out a travel coffee mug with a lid and wedge it into the corner on its side.

Since we do not have refrigeration, you will be using instant milk for your cereal. The Tupperware container of powdered milk is in the cupboard behind the stove. As you reach for it, the boat lurches into a wave and the spoon is thrown out of the bowl and tumbles over to the floor of the nav station. You abandon the process of getting the milk and do the unhook, hold, re-hook routine to retrieve the spoon. Then give it a quick rinse in the sink and place it on the silicone mat next to the bowl.

Finally, you can reach for the milk. You open the lid and set it on the counter, it promptly slides down to join the box of cereal and jar of coffee to your far right. You pick up the coffee mug and take off its lid (which also slides down to join the pile of things collecting at the far right edge of the counter). With the mug wedged into the crook of your left arm and the powdered milk held in your left hand, you carefully scoop spoonfuls into the mug. On the third scoop a gust of wind blows through the open companionway and the front of your shirt is covered in milk powder.

Once five scoops have made it successfully into the mug, you are ready to add water. When you turn the faucet, only a trickle comes out. Damn, you turned off the water pressure switch. You try to wedge the coffee mug into an upright position in the low corner of the counter so you can free your hands up to make the now familiar trip over to the panel in the nav station.

While you are away from the galley, the kettle starts to whistle. No problem, you can turn off the gas right here at the panel. Once roped in back at the stove, you make sure to turn off the burner (we have nearly blown ourselves up a few times by forgetting this simple step). Fortunately, the mug with powdered milk is still secure. You'll have to remember that spot for wedging the mug upright in the future. You add water, stir, cap it with the lid and return it to its position.

Open the box of cereal and pour flakes into the bowl. A few land on the counter and slide to the right. You pick them up and eat them straightaway, your hunger has truly grown by this time. You pick up the coffee mug and pour milk onto the flakes. At first, some milk dribbles onto the counter, because gravity is working at an angle today. But, you correct and get most of it where it belongs. You keep the amount low in the bowl, though, because you don't want it shloshing over the low side.

You leave a little milk in the coffee mug to take the edge off the strong cup you are about to prepare. While ordinarily you would put only one scoop of instant in a cup, this has been such a tribulation that you cannot see yourself making a second one. Therefore you make this one a double. Again, you hold the mug in the crook of your arm ready to receive the scoops. Unfortunately, the second scoop is caught by another gust of wind and instant coffee joins the powdered milk on the front of your shirt.

You wedge the mug back into position, unscrew the fiddle, and lift the kettle to pour hot water into the mug. This time you are careful to mind the tilted forces of gravity and no hot water escapes its intended destination. Kettle re-secured, coffee stirred, and you have yourself a meal.

Ordinarily, you would take your food out to the cockpit to eat, but the last time you did that with a bowl of cereal in windy conditions, soggy flakes flew out of your bowl. This morning you simply eat your breakfast standing tied to the stove in a tilted kitchen. When you are done eating, and finished washing your dishes, don't forget to turn off the water pump.

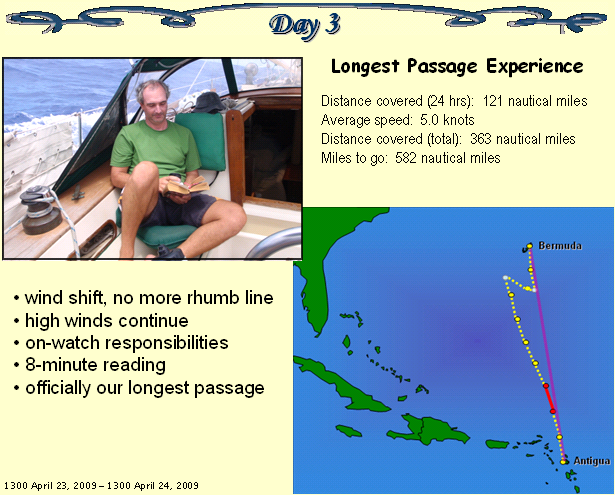

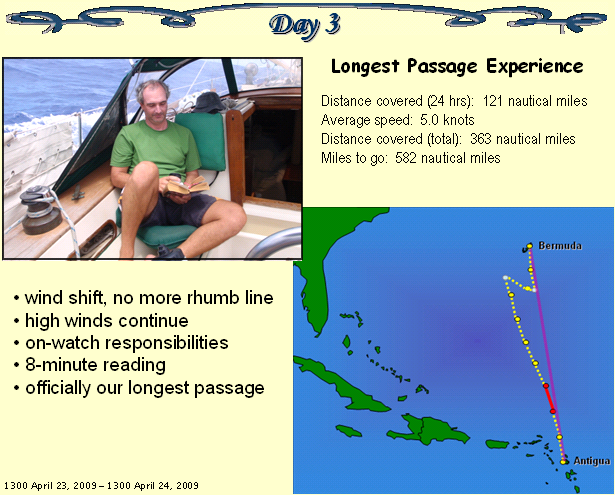

This morning I had the sunrise shift (4AM - 7AM). The sun rose behind a long line of squalls.

I spent the remainder of my shift hoping that they would not drift our way. Fortunately, they passed by our stern just as I was waking Sheryl with the 15-minute warning that it was soon to be her turn at watch.

Throughout the day, the winds have subtly shifted to the north. The beam reach we enjoyed during the first two days out first became a close reach, then we had to tighten up the sails to go close hauled. Regardless, by the end of the day we were drifting to the west of our rhumb line. No worries, though. We should get winds from other directions as we go north, so we'll work our way back to the east when the conditions are more favorable. For now, we'll simply let SUE keep us as close to the wind as possible while still making good progress in a generally northward direction.

Since SUE does the bulk of the work by steering the boat, on watch our only chores are monitoring our course, making minor changes to SUE, and managing sail trim. Oh and, most importantly, keeping a lookout for other boats.

I had expected that our boat sightings would become few and far between once we left the islands behind. I was wrong. Today there were 5 boat sightings, and one required that we tack to avoid getting too close. Since the cargo ships we are seeing are HUGE and could run over us without ever even knowing we were there, we take great care to keep a safe distance away from them. My personal safety zone at sea has a radius of 2 miles. If another boat approaches that circle on a course to cross my path, I prefer to change direction.

On previous passages, I have always watched the clock and done a visual scan of the horizon every ten minutes or so to check for boat traffic. On this trip, I am growing bored with this practice. So, I have started reading during daylight hours. In order to help me avoid getting lost in the paperback and forgetting my responsibilities while on watch, I have brought my small travel alarm clock out to the cockpit. I used to have to travel a lot with my job, and this cheap little clock has seen a lot of miles. Recently, though, it has simply been gathering dust.

The clock has an alarm with a sleep function. I set the time once and hit the sleep button every time a 'Beep-Beep-Beep' sounds. After eight minutes, the alarm sounds again. I read in 8-minute intervals, stand and turn a 360-degree sweep to scan the horizon, and return to my book. The daytime shifts are passing by much quicker now.

Sheryl has also been able to read. Her seasickness symptoms are gone. She, however, prefers not to be bothered with the 'Beep-Beep-Beep' of the alarm clock. She seems to have no trouble keeping a regular schedule of horizon scans without the aid of such technology.

Today it is official, completing a third day at sea makes this our longest passage ever.

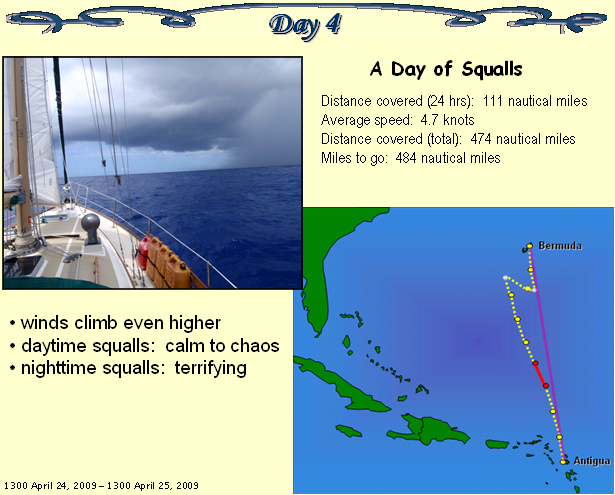

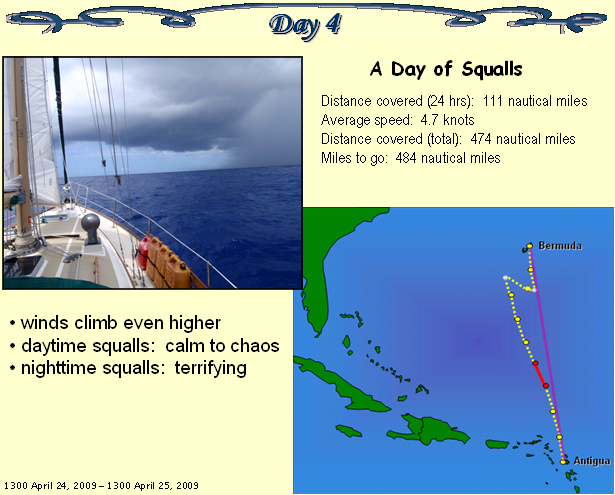

Late on Day 3 we successfully dodged a line of squalls. Today we were not so lucky. Just as the 1300 hour rolled around, a line of major squalls marched our way. Each one presented a similar pattern. First the wind dropped and we helplessly sat there in calm water watching this thing come toward us.

Once it neared, the winds suddenly went up to somewhere between 20 and 30 knots. The first one had winds in the low 20's. The second peaked out just over 30 knots. By the time we sat in calm water watching a third one headed our way, I did not want to see what kind of wind it would bring. We turned on the engine and tried to outrun it.

This turned out to be a waste of precious diesel fuel. We still caught the edge of the squall, and it had maximum winds near 30 knots. We shut the engine off after only 30 minutes of run time.

It is unsettling enough to run through these storms in daylight. At night, they are nothing short of terrifying. Although we are sailing near the time of the new moon and it is extremely dark at night, the starlight gives reasonable visibility to the dark-adapted eye. I could see this big squall coming from quite a distance away.

I woke Sheryl to help me pull in the genoa before it hit. When it did it was the worst one yet. This time, I let SUE keep the helm, and I was glad that I did. While I was tucked up under the dodger, max winds reached the mid 30's. SUE managed them better than I could have, keeping us extremely close to the wind and thereby subtly depowering the sails.

Once you are within the squall, the darkness is eerily close. What is bright grey during the daytime is a blanket of blackness at night. It is as though the boat has been transported to hell. My only solace is the fact that it will end soon. They always end, eventually.

By the time Day 4 was drawing to a close, we had lost count of the number of squalls we had survived. Interestingly, each time we passed through a squall, the winds on the other side seemed just a little bit stronger. By the time the clock read 1300, we were dealing with 25 knot sustained winds and no more squalls on the horizon. Conditions were sort of like an unending squall, though with good visibility.

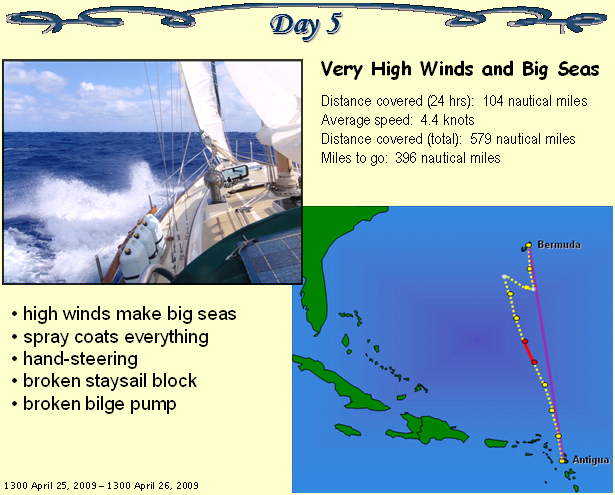

The continuous high winds (20-25 knots, with gusts over 30) caused the seas to build. Fortunately, with enough forward speed, Prudence does a great job of cutting through the waves. And, with this much wind, we were able to generate that speed with only the staysail and a single-reefed main.

Dancing through these waves causes a lot of spray in the air. Soon everything was coated with salt, including us. We started keeping the boards in the companionway in an effort to keep the salt-laden air from drifting down below. Still, it seemed, that via our own trips in and out the floor and all the surfaces we touched below became slick with salty residue.

Doing a 360-degree scan of the horizon takes longer now, because of the big waves. You have to time the scan of each section such that there aren't any nearby waves to blocking your view of the horizon. Then your progress is halted when the boat falls down into the valley between waves. You have to wait to get close to the top of the next wave to continue your scan.

It is amazing to watch and feel the boat move over these giant waves. For the most part they slide past and we simply go up and down. Sometimes, though, a wave will break at just the wrong time. If it hits the forward portion of the boat, the concussion sounds like a bomb has gone off and our speed will momentarily slow. If it hits the quarter, it can spin the back end in a sickening motion which leaves you wondering where your stomach wondered off to. In either case, a portion of the wave often lifts into the air and lands on deck and in the cockpit. Sitting under the dodger, we are saved from the soaking. The empty helm seat routinely gets splashed. Thank goodness for SUE.

As the day progressed, the conditions worsened. SUE was starting to whiplash the helm every time we fell off a steep wave. Concerned that something would eventually break, we switched to OTTO. His hydraulic arm keeps continuous pressure on the rudder post, stopping the dreaded whiplash action. We have plenty of power to run OTTO during daylight hours when the solar panels are generating juice, but we cannot keep him on all night. Our tricolor navigation light at the top of the mast is a true power hog (compared to all of the LED lighting we use elsewhere on the boat). We debated about adding another battery to the house bank while in Antigua, but the cost of their AGM batteries made us decide to forgo the luxury of more electrical storage capacity. We don't need it at anchor, and only rarely does the situation arise when we wish we had more power underway.

For the first time on this trip, we were going to have to steer the boat ourselves. Just as the sun was setting Sheryl took her position at the helm.

Only moments later, a loud bang was heard from the direction of the foredeck and a continuous 'whap-whap-whap' sound followed. The block from the staysail outhaul had broken.

I unclipped my tether from the cockpit and clipped it to the jackline, sliding it forward behind me as I went to secure the flapping sail. Fortunately, no damage (other than the destroyed block) had occurred. We dropped the sail and I tried once to re-rig something which would work for the night, but I couldn't get the foot of the sail tight enough. I lashed the sail with sail ties and would address the problem later, during daylight hours. It was a good thing this had happened before it became totally dark. Going forward in these conditions is scary enough as it is.

For the night, we unrolled a hankerchief-sized scrap of genoa (O.K. maybe a little larger than that, but not by much) and we were moving through the waves again at reasonable speeds. Sheryl went back to the helm, and I went below to try to get some sleep before the start of my shift at 10PM.

After I took my place at the helm, I heard Sheryl's voice drift up from the companionway. "I think we have a problem, but not a serious one." As she was taking off her salt-encrusted foul weather gear, she heard the bilge pump activate. We believe that we are taking on some water whenever the starboard side of the boat is soaked with a boarding wave. The amount is small, but it does accumulate in the bilge over time. It is really nothing to worry about, though, and we plan to address the issue when conditions settle a bit.

Sheryl looked into the bilge and observed that the water level did not go down. That is something to worry about. Fortunately, we have a manual bilge pump installed and another large capacity hand pump with long hoses which can be used in the event of an emergency; however one does not even like to think along those lines when one is over 400 miles from the nearest point of land. From the cockpit, standing at the helm, I pumped the manual bilge to lower the water level below the float switch and tried not to think negative thoughts.

With the crappy weather conditions, having to hand steer through the dark night, the recent explosion of the block on the staysail, and now learning that our electric bilge pump was out of order, it seemed as though things were beginning to fall apart. And we are only half the way to our destination.

It was a long night of hand steering, but I kept thinking that maybe by sunrise the winds would settle. Then we could focus on repairs. Unfortunately, when daylight finally returned we had to focus on repairs under the same weather conditions. Nothing had changed.

The bilge pump was my first priority. We disconnected the uptake hose and blew through. Water bubbled in the bilge. We turned on the pump and there was suction, but it felt a bit anemic. Fortunately, we are prepared for this. The summer before we departed, Sheryl had the full-time job of purchasing spare parts. We turned on the computer and the inventory list told us where to look. Under the starboard side of the v-berth, nestled next to the holding tank, was both a rebuild kit and a brand new bilge pump. I plan to install the new one now and rebuild the old one for a backup later (when we are at anchor).

The installation went smoothly, considering the boat motion, and before long we were flipping the switch to test our new bilge pump. It purred like a kitten. Unfortunately, the water level still did not go down. It was then that I noticed the flattened uptake hose. It must be clogged. We disconnected and blew through again, still bubbles getting through. O.K., time for a new hose. We consulted the inventory list again and I soon emerged from the bouncing v-berth with 30-feet of hose. We threaded it down into the bilge and connected it to the new pump. This time when the switch was thrown, the water level went down. Yay team!

After a single night of hand-steering, we knew that we needed to address SUE's whiplash issues. There were no signs that conditions were going to improve before this coming nightfall. Sheryl worked to tighten her new steering lines such that there was absolutely no slack in the system. We also tried applying a little bit of the binnacle brake (which we use to hold the wheel in one place) to put a little more resistance in the system. The combination of the two worked. SUE was back in business.

We are now quite firmly into the horse latitudes. However, big winds and big waves continue unabated. Sheryl suggests that the horse latitudes must be named as such because we are galloping along like an out of control colt. We wear our harnesses and tethers all the time we are in the cockpit now (not just at night), as the fear of getting bucked off is just to frightening to imagine.

There is one more fix I have yet to attend to, and I was hoping that conditions would settle before I would go back on deck. As our supply of daylight hours were rapidly dwindling, I went forward to put a new block on the staysail. This turned out to be an easy fix, despite the mechanical bull-like conditions. I tightened up the outhaul and made ready to raise the sail. Now, if only the winds would relax a little to make raising the sail easier.

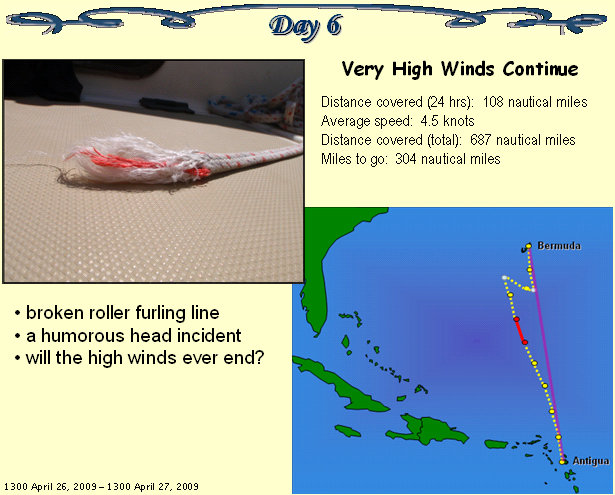

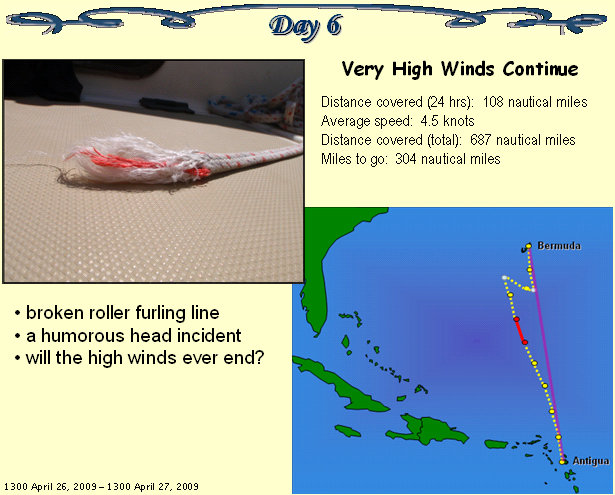

Just as one thing is fixed, another fails. And, again, it happens immediately before sunset. Launched with another boom, this 'whap-whap-whap' had a much deeper tone and caused the entire boat to shake. The furling line had chafed through and the entire genoa had unrolled in 25 knots of wind. It was Sheryl's turn to go forward.

Fortunately, where the line broke left plenty of furling line in tact to be used to roll up the genny. Unfortunately, Sheryl would have to re-rap the length of line on the bow of the boat in less-than-ideal conditions. As I watched my babe bounce up and down, wrestling with line, I tried to keep the boat slowed and the genoa under control. With just the right tension on the sheet, I could keep a little air in the sail, but spill the rest out the top of the sail. I think Sheryl only got hit once in the face with a flapping sheet while I was figuring this out.

Soon she had walked the furling line back to the cockpit and I was ready to roll it in. I don't usually use the winch for this, but then again, I don't usually have the full sail up in 25 knots of wind. The relative silence which followed was absolute bliss. We returned to our favorite sail configuration of the trip, staysail with a single-reefed main.

The nighttime hours teased us with a few brief periods of wind in the lower 20s and a peek at some high teens (which we have not seen for days). Unfortunately, daybreak brought a return to the 25-30 knot apparent wind numbers and the waves seemed taller than ever.

Everything is challenging under these conditions. When the boat drops off a wave, there is a decrease in gravity, followed by a surge of g-forces you wouldn't believe. Add to this the fact that the force of this extreme gravity is sideways and you encounter issues you could never imagine if you hadn't experienced it. Take for instance a recent trip I made to the head. Even the most manly of men will sit to pee under these conditions, and I am no exception. As I sat there, with my shoulder wedged against the counter to keep from sliding off, I noted that that particular spot on my shoulder is getting sore from repeated use in this circumstance. Days of bracing myself there were leaving a bruise.

Our toilet paper resides on a dowel rod delivery device mounted just inside the door beneath the sink in the head. I have to shift my knees aside to open this door, putting additional strain on my shoulder-bracing sore spot. As I am trying to unroll a few squares, we fall off a wave and the roll is bumped from its holder. The roll falls into the space beneath the sink and the dowel rod falls to the floor. As I am reaching around on the floor with my hand feeling around and trying to locate dowel rod, another even larger wave sends a shocking g-force increase through the boat. I slide sideways on the seat and hear a thump behind me as the hinges of the seat have slid off and the lid to the toilet falls to the floor.

I decide to leave everything in disarray until I can gather myself together. Once I am standing, I replace the toilet paper and its dowel. I pick up the toilet lid and put it back on the hinges before pushing the seat sideways to hold it all in place again.

Now it is time to wash my hands. Did I mention that we use a foot pump to deliver water in the head (saves the walk back to the panel in the nav station to turn on the water pump)? Imagine trying to hold your hands beneath the faucet while standing on one foot and pumping with the other in these conditions. This is why we have grown to love instant hand sanitizer. It also helps save on water.

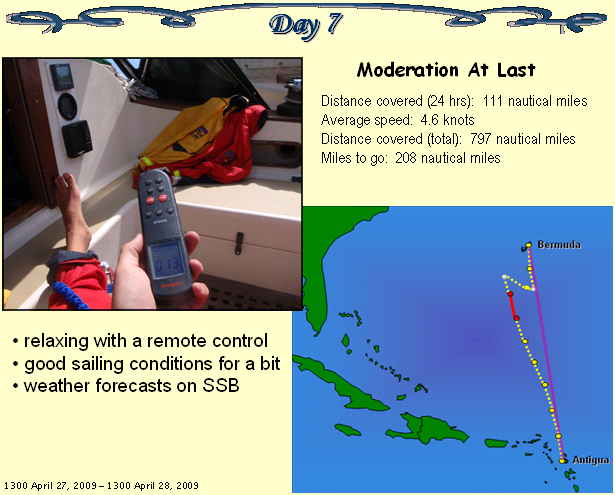

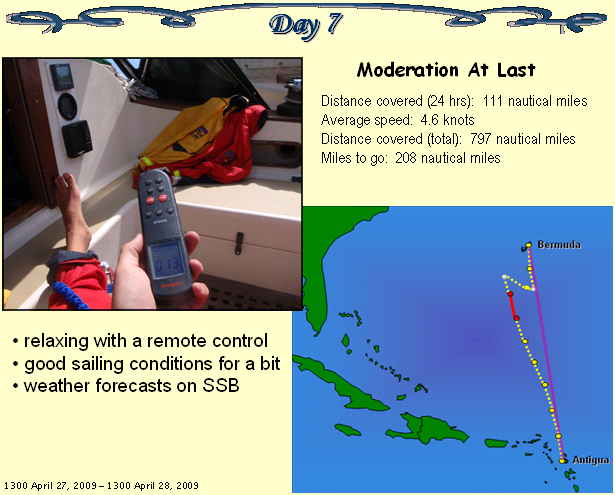

Not too long after the clock turned 1300 we finally saw some smaller numbers on the wind indicator panel. This time it was not just a tease, this was real and true moderation. We were able to roll out a full genoa. I actually took the helm for a while just for fun!! With fifteen knots of wind the sailing was just lovely.

Eventually, I decided to give the steering task back to our automated crew. With the sun high in the sky, I decided to give OTTO a go. One of the things I have missed ever since we left a land-based lifestyle behind is holding a remote control in my hands. OTTO gave me my fix out there in the middle of the Atlantic.

With the remote control for OTTO in hand, I can sit comfortably on my sport-a-seat cushion and take in all the action like the couch potato I truly am. I can see the instruments (speed, position, wind strength and direction), and I can see the sails. By pushing a button, I can change our heading in 1-degree increments, in an effort to get as close to the wind as possible while still maintaining speed. How cool is that?

Just to give SUE fair acknowledgement in this regard, she too has remote controls (of sorts). They are just not as slick-looking. To control SUE, you pull on one of two lines. This line 'clicks' a gear on a swiveling table that supports the position of the wind vane. Each click results in 3-degrees of change in heading. I have extended the length of these lines so that I can sit anywhere in the cockpit and pull the control cords.

Fun time was over when Sheryl poked her head out the companionway and said, "Come look at this." She had taken apart some of the cabinet in the galley and discovered the source of our leak. A hose had partially slid down off of the deck scupper and when large amounts of water went down the scupper a small amount leaked in and ran along the hull to the bilge. Since it was Sheryl's turn on watch, and my arms are longer anyway, I would take the task of repairing this problem.

I had to round up some more spare hose and a few hose clamps, and the area I was working in was hard to reach, but I eventually got it all together and we are certain that this will cure the water accumulation in the bilge.

Today was the first time I was able to get a weather forecast out here at sea. NOAA weather is broadcast at certain times of the day on specific high frequency channels. NMN is the call sign for this automated audio signal, pronounced November-Mike-November. Sheryl and I just call him Mike. Through our SSB receiver I have been trying to listen to Mike each day, but he just wasn't coming in strong enough to hear. Today I got him, reasonably clear enough to make sense of the general overall weather picture.

I record the forecasts on a small digital recorder and download them onto the computer. Here I can play them back slowly, pause, and jump to specific times in the recording. I do this and make notes, then take them to Sheryl and share the weather information I have gathered. Over several days, we begin to get a handle on weather conditions across the north Atlantic and have a good idea of what we should expect. Today the word is moderation going forward. Winds should remain out of the northeast. This will keep us on our current course increasing our westward distance from our rhumb line.

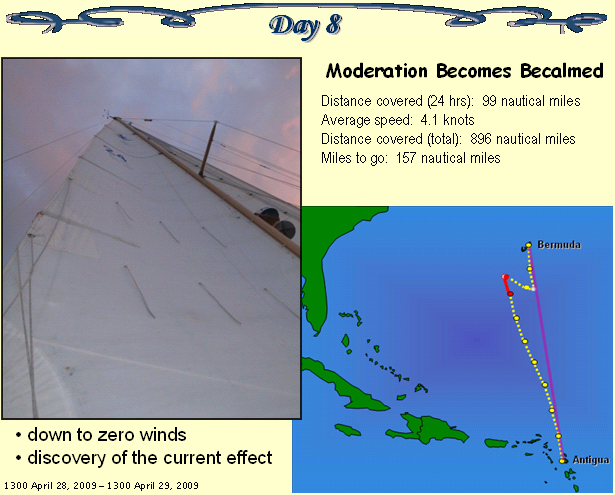

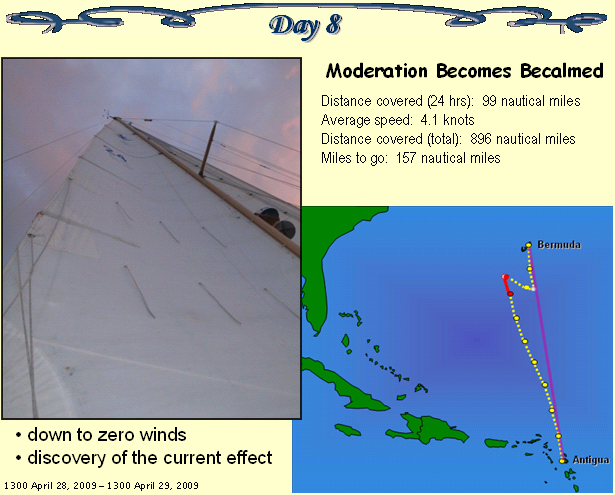

Well, Mike told us to expect it, and he was right, the moderation continued. We have raised full sail, and still this is not enough to keep the boat moving.

For a few hours we sit becalmed. The sails swing around slightly, but are of little use. At least there is no swell. It is here that we discover another reason that we have not been able to stick to our rhumb line. There is a current. In fact, there is a HUGE current. We are drifting to the west-northwest at over 2 knots!

We consider turning on the engine and motoring in the direction of Bermuda. With 200 miles to go, we are safely within the range of our fuel supplies. But neither of us wants to listen to the engine drone on for the next two days. So we wait, we enjoy dinner (which was exceptionally easy to prepare in the current conditions). We try to recall that we were suffering with big winds and big seas only a short time ago.

Eventually, a little wind reaches us and we can make the boat move along its continuing course as close to the wind as possible. Throughout the night, we experience light winds alternating with times where we are becalmed and drift with the current. It is a frustrating way to spend the night.

Frustrations and fatigue are beginning to show themselves more readily. Sheryl and I are, at times, a little short with each other. We vent at the only available person, the one we love the most. "I'm sorry," is quick to follow, but it still feels wrong when your hurting spills over onto someone else in this way. Sometimes this sailing life really sucks.

With morning light comes a change. A line of showers passes over and on the other side we find wind. Apparent winds in the mid to high teens eventually have us rolling in a portion of the genoa.

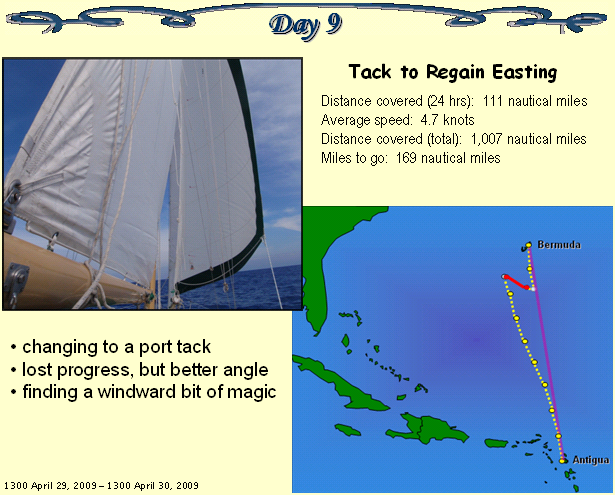

Mike came in well again today. We had been considering skipping Bermuda and heading directly to the United States, especially since we are now over a hundred miles west of our rhumb line. However, the fronts passing over the east coast this weekend have made us shy of pursuing that option. Instead, we have decided to commit to Bermuda as our destination by tacking to the east.

So, once again we are headed east, trying to get as close to the wind as possible (sound familiar?).

It feels odd to be on a port tack after over a week on a starboard tack. We had gotten used to our world at that angle ...

... and now it has all changed. With the lighter winds, our angle of heel is not quite as extreme on this side but it is still noticeable. Working in the galley no longer requires the rope, instead you lean your body against the stainless steel bar. I stand in a different spot and lean on something new to struggle into and out of my foul weather gear. And our sleeping berth has you leaning on the table side rather than the seat back side.

The wind direction has us sailing slightly south of east. Over time we are losing a bit of distance from Bermuda; however, we should arrive at a position where we can sail directly to Bermuda when we tack back to the north.

I have worked hard getting the sails tuned optimally, and Sheryl has gotten SUE clicked to the position where she is right on the edge of keeping the sails full vs. luffing. Tell-tales are streaming aft and we are making over four knots of eastward progress with only 8-12 knots of apparent wind.

At some point in the evening, this balance strikes some sort of magical state. All of the sudden we are pointing effectively only 30 degrees off the apparent wind! To understand the magnitude of this event, we generally can point only 40 degrees off the wind on our best days. I don't understand what is happening here, but I am afraid to touch anything in the event that I might disrupt the magic.

We exchange shifts through the nighttime hours and the magic remains. We continue to touch nothing until the early morning hours present us with a big ship. Its outline on the horizon is narrow (that is a bad sign, because we are looking at the boat head on and not broadside). It is coming right at us. We have to tack to avoid allowing the vessel into our proximity zone.

The ship passes and we return to our port tack, but the magic never comes back. With the sun shining brightly, I abandon SUE for OTTO and return to the remote control approach of milking out all of the eastward progress I can without going too far south.

Our clock rolls past 1300 and we are still on a port tack. Mike has suggested that the winds may shift slightly south today. That is the good news. The bad news ... further moderation is expected.

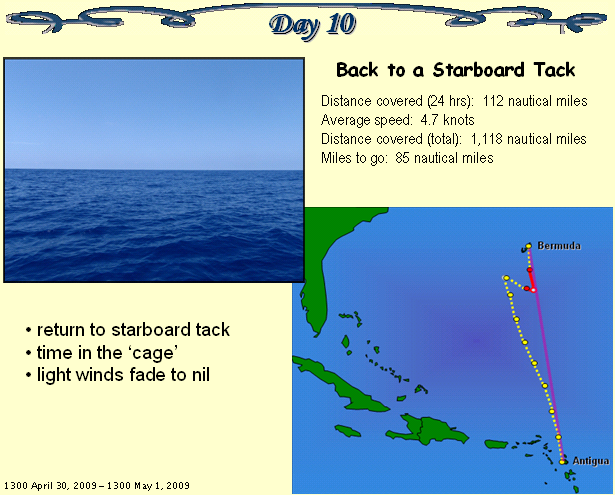

The time has come to go back to a starboard tack. We make the tack at the beginning of the 1600 hour shift change.

I try in vain to reclaim that close-to-the-wind magic of the previous evening, to no avail. In fact, I cannot even seem to get SUE to keep us on a consistent heading. Something weird is going on. We both struggle with it on each of our shifts throughout the night, constantly adjusting SUE with click after click, just to keep on course.

When my shift starts at 0400 hours, I have had enough. I abandon SUE for hand steering. Once again I am in the cage. We call being behind the helm 'in the cage' because you are surrounded by stainless steel bars. The stern pulpit and bimini were there when we purchased our Southern Cross. We added solar panels above the bimini which added a few more bars to support that weight. It is a comforting feeling in rough weather to know that you are secure within the cage. It also provides many hand holds when you are standing at the helm, one hand on the wheel and one on stainless.

I think I have figured out what was causing us problems. It is that strange cross-current. It is taking the edge off of the weather helm. SUE relies heavily on just a hint of weather helm to help her steer the boat. When the sun is up and the solar panels are charging again, I give the boat over to OTTO. All he needs is a compass heading and he happily steers us onward.

We are starting to notice the change in climate with this far northward position. It is comfortable enough in the cockpit wearing shorts as long as the sun is out. When the sun goes behind a cloud, it is a bit chilly.

We have merged with our original rhumb line about 100 nautical miles south of Bermuda. However, as the end of Day 10 draws to a close at 1300, the winds are fading fast. The moderation Mike predicted is upon us. Just before the 1300 hour strikes, the wind drops to less than 5 knots. The flat calm of the water suggests that it will not return anytime soon.

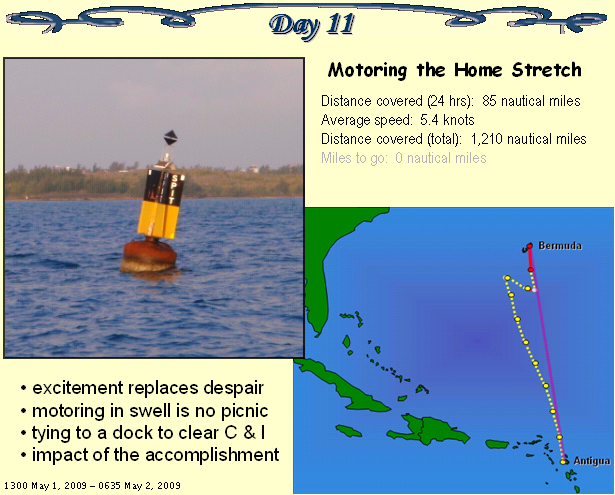

We started this day by starting the engine. We are not inclined to wait what could amount to a few more days for the winds to return. We will not have a Day 12. We should arrive in Bermuda before the clock strikes 1300 again.

The final distance is covered in under 20 hours. During this time, we continue our shift schedule through the nighttime hours. Sheryl is so excited she cannot sleep. Even the noise of a diesel engine running only a few feet away cannot keep me from getting a few hours of shuteye. I need my rest for the stressful task of bringing Prudence up to a dock.

We contact Bermuda Harbour Radio when we are 20 nautical miles out. All mariners must report their positions to this station. They serve as traffic controllers for the waters of Bermuda. Sheryl is greeted by a friendly voice with a British accent. We had sent a form with all of our information ahead via e-mail, and this makes the process quite simple. They immediately recognize the name of the boat, and check a few items on the form for accuracy. We don't have to play 20 questions like the boats who have not submitted this form. The data is collected to aid in any search and rescue efforts the authorities might be called upon to undertake.

We indicate that we plan to arrive off the entrance to St. George's Harbour at first light. Bermuda Harbour Radio asks us to call them back at that time. We slow the engine speed to give us a 4-knot velocity and time our arrival with that of the sun.

The flat waters from early evening have become quite lumpy. There is still no wind to fill the sails and stabilize the boat so we spend the last 5 hours or so wallowing uncomfortably in the swell as we motor onward. Regardless, spirits are high. We are almost there!

First light reveals land for the first time in 10 days. We contact Bermuda Harbour Radio as we reach the SPIT buoy and are given permission to enter the town cut.

After so long at sea, it is amazing to be this close to land, yet still not off the boat. We can smell the scent of pine trees in the air. It is decidedly not a Caribbean-type smell. We have come a long way.

Bermuda Harbour Radio gives us directions to the Customs and Immigration dock. I am happy that the winds are light. Happier still when we round the corner to Ordinance Island and find that the dock is empty. We are the first ones here.

The dock is positioned in a narrow dead end waterway. Because there is no traffic at this hour, I decide that it would be best to turn the boat around now and dock facing out. With several early risers on shore watching, I execute a perfect three-point turn (using the prop walk to assist me in the process). Onlookers must think I know what I am doing. It is a good thing that conditions are so perfect (calm winds and no traffic), otherwise they might get an entirely different show.

Two gentlemen wait on the dock to take our lines, and I am relieved to have us safely tied off at the dock.

They are exceptionally friendly here as we receive a warm Bermudian welcome. Captain Sheryl gathers her paperwork and proceeds into the Customs office. Meanwhile, I sit on the dock and stare into the clear water below. I can't believe we are here. We sailed our boat over a thousand miles from Antigua to Bermuda. Wow!

A catamaran came into the dock just after we did, so once we are cleared with the officials, we need to get off the dock and around this other boat. With Sheryl at the helm, the gentle winds push us back slightly and she expertly navigates us out of the narrow channel. It is only a few short yards to the anchorage. With a splash our big CQR drops below the surface once again. Even though it is only 8AM, it is time for a celebratory splash of scotch.

CURRENT LOCATION: Anchored in St George's Harbour, Bermuda

32 22.748' N, 064 40.405' W

Sheryl, in particular, felt that our cruising experience was lacking in one regard ... a long offshore trip. Our longest to date had been just under three days. All of the cruising couples we have spoken to who are experienced offshore sailors say that everything changes after day three. It was our time to develop our own opinion on the matter.

During some more arduous portions of the trip, I rhetorically asked Sheryl, "Is this the experience you were looking for?" However, shortly after completing this journey, I asked the same question with less sarcasm in my voice. Her smile in return said it all.

Synopsis: We have just completed the passage from Antigua to Bermuda. It took 11 days and added over 1,200 nautical miles to our sailing bailiwick. We experienced everything ranging from big winds pushing us through big seas to struggling to make the boat move in calm conditions. In addition, a conniving current took its usual toll on our overall progress. Stuff broke, but we managed to effect repairs and continue onward. The biggest physical challenges were sleep deprivation and living in a cockeyed home with extreme increases in gravity occurring at random intervals. The biggest mental challenge was the extreme isolation, knowing that assistance on any matter from mechanical to medical was completely and utterly absent.

Cast: Aboard our 35-foot Southern Cross sailboat, Prudence, the following persons and machines contributed to a successful passage:

Doug - listed first only because I am the first-person author of this blogDaily blogs: Each day of the trip is detailed below. Please enjoy the central theme as well as the overarching tale of a long, long journey (both of geography and of self-discovery):

Sheryl - my lovely wife, and the only person in the world with whom I would want to share this experience

SUE - wind-directed/water-powered steering system

OTTO - compass-directed/electric-powered steering system

We woke on Tuesday, April 21st, our departure date, brimming with anticipation. Unlike a lot of our shorter journeys, there was no driver to make a first light departure, so we were able to enjoy breakfast before seeking resolution to the remaining items on our pre-departure checklist. The cereal had to compete with an active bunch of butterflies for space in my stomach. Getting busy getting ready was to be the best treatment for my mounting anxieties.

While Sheryl took our dinghy, Patience, to town to made a final trip to the grocery store to get fresh eggs and bread and then to check out with Customs and Immigration, I reorganized the cockpit locker contents and stowed other items in more offshore-friendly locations. Our v-berth is unsuitable for sleeping while underway. The motion of the boat that far forward can be likened to a ride on the Vomit Comit. Therefore, the space can be used for storage. Certain items can be laid out on top of the berth to be grabbed easily rather than having to be dug out of a locker while underway.

Upon Sheryl's return, we hauled the engine from the dinghy and the dinghy from the water. While I deflated and disassembled the dinghy, Sheryl re-organized some items in the cabin. Our appetites generally suffer while underway, and the degree of difficulty in food preparation increases exponentially. Consequently, we are doing all we can to make access to food simple. Quick cooking one-dish meals are planned and snacks will be readily available in a hammock hanging above the starboard settee.

Because the v-berth is such a bucking bronco when underway, we have packed our clothing in bags and secured them behind a lee cloth on the starboard settee. Digging out that sweatshirt I haven't worn in over a year and a half might have been a pain to accomplish in a couple of days. Now it will not require an hour in the forward area of the boat. That job is already done.

On previous passages, our inflatable kayaks were stored between the table and the port settee, making a narrow place in which to wedge oneself into a somewhat cozy sleeping berth. Because we sold the kayaks, and because this was to be such a long passage, we decided to open the berth into its sleeping orientation. Because most of the trip would be on a starboard tack, this should provide a spacious and comfortable sleeping space on the low side of the boat for the off-watch person. We dubbed this area 'The Nest.'

We double and triple checked everything on deck and below. Items needed to be secure yet accessible when needed. We took down the Antigua courtesy flag and started the engine. By 1PM, we had the anchor off the bottom of Mosquito Cove and were underway.

Since sailing our boat will now be a 24-hours a day - seven days a week operation, we have decided that each new day will start at 1300 AST. Therefore, please be aware that each 'day' described below starts and ends at the mid-day hour of 1300 hours.

The engine was turned off less than 1 hour after it was started. Shortly after that, SUE was engaged to steer the boat. Last week, Sheryl took the time to replace all of the steering lines on SUE with new rope. The new line was working well and would eventually pay great dividends toward our individual energy levels over the days to come.

Although the anxiety level was high on the days leading up to departure, I feel like a weight has been lifted off of my shoulders. Now, the decision point has passed. We are committed to this endeavor. That is not to say that I am no longer anxious, a certain baseline of anxiousness accompanies me anytime we are underway. I simply feel ready to take on this challenge and face my fears.

In our past experiences with extended passages, the weather forecast is generally reasonably accurate for the first day or two. We elected to depart at a time where the trades were going to be blowing pretty strong (15-20 knots). We knew, however, that the wind direction would put us on a beam reach and we could make good speeds even with sails reefed (which we prefer to do at night). Getting a couple of days of good progress in the beginning would be important to our morale and would get us totally clear of these pesky islands. The idea here is that lots of sea room will allow us to take any orientation we needed to be comfortable in the event of really, really strong winds and high seas.

Because we chose to depart in somewhat boisterous conditions, the motion of the boat was fairly drastic. Sheryl has suffered from seasickness ever since our first extended offshore passage, back in November 2007. Since then, she has found medication and techniques to manage this malady. It is not entirely eradicated, but it is subdued enough to allow her to function. When these moderated symptoms hit her on this trip, I could tell. She bravely shrugged them off, stating, "I just hope that what everyone says about seasickness going away after a few days is true. I look forward to being able to spend time below or even read a book later this week."

I have never suffered from sea sickness. I do get the occasional queasy feeling when trying to do chartwork below in rough conditions, but never the full-blown symptoms I have observed in others. This time it got to me. As the morning sun rose and we headed toward the completion of our first 24 hours underway, I found that my breakfast was not settling well. I will spare you the graphic details and simply state that I was under the weather for a spell.

Sheryl, still suffering from her own sea-induced sensations, rose to the occasion and took care of me ... selflessly granting me a little extra sleep time, going below so that I would not have to, and gently encouraging me to eat (even if only to nibble on a few saltines). That, my friends, is true love.

The morning hours brought us a squall. Each squall has its own characteristics, but when we spot these things on the horizon, we immediately think of increasing winds. In actuality, this squall we passed through brought both extremes. First, the winds died. We drifted in 0 knots of wind. Because SUE doesn't know what to do with zero knots of wind, I took the helm. Then, just before the rain started, the winds picked up to 20 knots in an instant. Water soon joined the onslaught from the cloud above and visibility dove down to near nothing. The situation is not fun, and I simply hope that we never meet another boat while sailing through a squall.

Fortunately, squalls usually pass after only a few minutes, and this one was no exception. As we passed out through another section of diminished winds, we watched it move on. Eventually, the winds built back to normal levels and the sun returned to dry out our well-soaked cockpit.

Both Sheryl and I are feeling better today, the effects of sea sickness are waning. We are beginning to acclimate to life underway. It is a matter of accepting the circumstances, though, not necessarily one of enjoying them.

First and foremost, let's talk about sleep. On our previous passages, this was always our biggest struggle, for me especially. I simply could not sleep well when underway. After one or two nights at sea, I would arrive at our destination thoroughly exhausted. When I extrapolated this to the length of our current passage, I worried that I might simply parish from the fatigue.

As it turns out, though, I fell into a pattern of sleeping fairly early into the voyage. Perhaps it was knowing that I just had to do it. Or, maybe it was because sleep was the only way to escape the sensations of seasickness. Regardless, it was good.

Unfortunately, one never quite gets enough sleep while underway. With only two of us having to cover a 24-hour watch, there is only so much time for uninterrupted sleep. Although we have tried other schedules, we decided that for this trip we would work 3-hour shifts. We start shiftwork at 1600 hours (4PM) and alternate watches every three hours until 1000 (10AM). Each day we switch shifts, one day Sheryl will start at 4PM and the next I will. This gives us both an opportunity to enjoy events like sunsets and sunrises. During the daylight hours from 10AM-4PM, we operate under a slightly less regimented plan where we simply take our even share of those hours, based on the day's whim.

Considering that schedule, what it boils down to is this. For two people who have grown quite accustomed to a full night's sleep (without even the interruption of a morning alarm clock), we are getting less than 3 hours of continuous sleep at any one interval. It is like hearing a snippet of a song you really, really like. You long to hear the whole thing. We crave a continuous, uninterrupted, night's sleep. Unfortunately, it will be a long time yet before we can satiate that craving.

In this world of modified schedules, other things change. You don't realize how much of your daily routine revolves around subtle cues, like going to sleep at night and waking up in the morning. Those, for me, are triggers to brush my teeth. Currently, I am brushing my teeth at least six times a day.

Meals also lack the normal temporal regularity. I find that I eat underway only when I am really, really hungry. Part of this is because anxiety affects me as an appetite suppressant, and as stated previously: I am always anxious while underway. The other part is that making food is a real chore. Our galley has several wonderful features which help, but it is still a chore.

Imagine yourself standing in the galley above. You are hungry and you want to make something as simple as a bowl of cereal and a cup of coffee. The coffee is instant, so first you need to start some water heating in the kettle. Because the boat is heeled to the port side and bouncing over waves, you have to hang on to the stainless steel bar in front of the stove with one hand to keep from being tossed over into the navigation station (this happened once to Sheryl, and it was not fun). You must hold on at ALL TIMES, otherwise you will fall.

So you pick up the kettle with one hand, but do not have a free hand to turn the faucet. Never fear, we have a solution. You set the kettle back down and loop the rope hanging in front of the stove behind your back and clip it to the other side. With the rope holding your weight, you have both hands free. You pick up the kettle again and turn the water faucet. Unfortunately, only a trickle comes out because you have forgotten to turn on the water pump (we leave it off in case a leak develops in the system and all our fresh water gets pumped into the bilge).

So, you set the kettle back down. Unhook the rope while holding on with the other hand and ease yourself over to the panel above the navigation station. Once the switch for the water pump is turned on, you climb back up to the galley and secure yourself once again with the rope. Now you can finally fill that kettle with water.

O.K., time to light the stove. But wait, the LP switch is off (as a safety precaution, a switch controls a solenoid which shuts off the flow of propane gas into the boat; again, we keep this off when not in use in case a leak develops in the system). So, you are going to have to go back to the panel in the navigation station.

The stove tilts from port to starboard on what is called a gimbal, preventing the heeling of the boat from effecting your cooking; however, you are also experiencing some occasional pitching motion. To be safe, you lock the kettle full of water on the stove with the use of fiddles. These little bars sit on each side of the pot to prevent fore/aft motion and lock to the stove with the use of a thumb screw.

Once the kettle is secure, you repeat the dance down to the nav station and flip the LP switch. While you are there, you also turn off the water pump (just out of habit), then back up to the galley and re-attach the rope. Now light a burner, loosen the fiddle, move the kettle to the burner, and tighten another fiddle. Whew, all that just to boil water.

Now you need to round up the supplies. Cereal and instant coffee are stored in the well set into our table. So you unhook the rope again and use handholds to work your way over to the table. You pop the lid on the well and take out what you need. Meanwhile, the lid slides sideways onto the sleeping berth. You'll be putting these things away later, so you just leave it there.

With a box of cereal and a jar of coffee crystals cradled awkwardly in one arm, you handhold your way back to the galley and place the items on the counter. You have to lie them down so that the lip on the counter will hold them in place, otherwise they will topple over and tumble into the nav station.

You secure yourself with the rope and get out a bowl and spoon, placing them on the counter. We have a couple of silicone hot pads which stick to the counter pretty well. Placing the bowl on one keeps it from sliding down upon the box of cereal and jar of coffee. You put the spoon in the bowl. You also get out a travel coffee mug with a lid and wedge it into the corner on its side.

Since we do not have refrigeration, you will be using instant milk for your cereal. The Tupperware container of powdered milk is in the cupboard behind the stove. As you reach for it, the boat lurches into a wave and the spoon is thrown out of the bowl and tumbles over to the floor of the nav station. You abandon the process of getting the milk and do the unhook, hold, re-hook routine to retrieve the spoon. Then give it a quick rinse in the sink and place it on the silicone mat next to the bowl.

Finally, you can reach for the milk. You open the lid and set it on the counter, it promptly slides down to join the box of cereal and jar of coffee to your far right. You pick up the coffee mug and take off its lid (which also slides down to join the pile of things collecting at the far right edge of the counter). With the mug wedged into the crook of your left arm and the powdered milk held in your left hand, you carefully scoop spoonfuls into the mug. On the third scoop a gust of wind blows through the open companionway and the front of your shirt is covered in milk powder.

Once five scoops have made it successfully into the mug, you are ready to add water. When you turn the faucet, only a trickle comes out. Damn, you turned off the water pressure switch. You try to wedge the coffee mug into an upright position in the low corner of the counter so you can free your hands up to make the now familiar trip over to the panel in the nav station.

While you are away from the galley, the kettle starts to whistle. No problem, you can turn off the gas right here at the panel. Once roped in back at the stove, you make sure to turn off the burner (we have nearly blown ourselves up a few times by forgetting this simple step). Fortunately, the mug with powdered milk is still secure. You'll have to remember that spot for wedging the mug upright in the future. You add water, stir, cap it with the lid and return it to its position.

Open the box of cereal and pour flakes into the bowl. A few land on the counter and slide to the right. You pick them up and eat them straightaway, your hunger has truly grown by this time. You pick up the coffee mug and pour milk onto the flakes. At first, some milk dribbles onto the counter, because gravity is working at an angle today. But, you correct and get most of it where it belongs. You keep the amount low in the bowl, though, because you don't want it shloshing over the low side.

You leave a little milk in the coffee mug to take the edge off the strong cup you are about to prepare. While ordinarily you would put only one scoop of instant in a cup, this has been such a tribulation that you cannot see yourself making a second one. Therefore you make this one a double. Again, you hold the mug in the crook of your arm ready to receive the scoops. Unfortunately, the second scoop is caught by another gust of wind and instant coffee joins the powdered milk on the front of your shirt.

You wedge the mug back into position, unscrew the fiddle, and lift the kettle to pour hot water into the mug. This time you are careful to mind the tilted forces of gravity and no hot water escapes its intended destination. Kettle re-secured, coffee stirred, and you have yourself a meal.

Ordinarily, you would take your food out to the cockpit to eat, but the last time you did that with a bowl of cereal in windy conditions, soggy flakes flew out of your bowl. This morning you simply eat your breakfast standing tied to the stove in a tilted kitchen. When you are done eating, and finished washing your dishes, don't forget to turn off the water pump.

This morning I had the sunrise shift (4AM - 7AM). The sun rose behind a long line of squalls.

I spent the remainder of my shift hoping that they would not drift our way. Fortunately, they passed by our stern just as I was waking Sheryl with the 15-minute warning that it was soon to be her turn at watch.

Throughout the day, the winds have subtly shifted to the north. The beam reach we enjoyed during the first two days out first became a close reach, then we had to tighten up the sails to go close hauled. Regardless, by the end of the day we were drifting to the west of our rhumb line. No worries, though. We should get winds from other directions as we go north, so we'll work our way back to the east when the conditions are more favorable. For now, we'll simply let SUE keep us as close to the wind as possible while still making good progress in a generally northward direction.

Since SUE does the bulk of the work by steering the boat, on watch our only chores are monitoring our course, making minor changes to SUE, and managing sail trim. Oh and, most importantly, keeping a lookout for other boats.

I had expected that our boat sightings would become few and far between once we left the islands behind. I was wrong. Today there were 5 boat sightings, and one required that we tack to avoid getting too close. Since the cargo ships we are seeing are HUGE and could run over us without ever even knowing we were there, we take great care to keep a safe distance away from them. My personal safety zone at sea has a radius of 2 miles. If another boat approaches that circle on a course to cross my path, I prefer to change direction.

On previous passages, I have always watched the clock and done a visual scan of the horizon every ten minutes or so to check for boat traffic. On this trip, I am growing bored with this practice. So, I have started reading during daylight hours. In order to help me avoid getting lost in the paperback and forgetting my responsibilities while on watch, I have brought my small travel alarm clock out to the cockpit. I used to have to travel a lot with my job, and this cheap little clock has seen a lot of miles. Recently, though, it has simply been gathering dust.

The clock has an alarm with a sleep function. I set the time once and hit the sleep button every time a 'Beep-Beep-Beep' sounds. After eight minutes, the alarm sounds again. I read in 8-minute intervals, stand and turn a 360-degree sweep to scan the horizon, and return to my book. The daytime shifts are passing by much quicker now.

Sheryl has also been able to read. Her seasickness symptoms are gone. She, however, prefers not to be bothered with the 'Beep-Beep-Beep' of the alarm clock. She seems to have no trouble keeping a regular schedule of horizon scans without the aid of such technology.

Today it is official, completing a third day at sea makes this our longest passage ever.

Late on Day 3 we successfully dodged a line of squalls. Today we were not so lucky. Just as the 1300 hour rolled around, a line of major squalls marched our way. Each one presented a similar pattern. First the wind dropped and we helplessly sat there in calm water watching this thing come toward us.

Once it neared, the winds suddenly went up to somewhere between 20 and 30 knots. The first one had winds in the low 20's. The second peaked out just over 30 knots. By the time we sat in calm water watching a third one headed our way, I did not want to see what kind of wind it would bring. We turned on the engine and tried to outrun it.

This turned out to be a waste of precious diesel fuel. We still caught the edge of the squall, and it had maximum winds near 30 knots. We shut the engine off after only 30 minutes of run time.

It is unsettling enough to run through these storms in daylight. At night, they are nothing short of terrifying. Although we are sailing near the time of the new moon and it is extremely dark at night, the starlight gives reasonable visibility to the dark-adapted eye. I could see this big squall coming from quite a distance away.

I woke Sheryl to help me pull in the genoa before it hit. When it did it was the worst one yet. This time, I let SUE keep the helm, and I was glad that I did. While I was tucked up under the dodger, max winds reached the mid 30's. SUE managed them better than I could have, keeping us extremely close to the wind and thereby subtly depowering the sails.

Once you are within the squall, the darkness is eerily close. What is bright grey during the daytime is a blanket of blackness at night. It is as though the boat has been transported to hell. My only solace is the fact that it will end soon. They always end, eventually.

By the time Day 4 was drawing to a close, we had lost count of the number of squalls we had survived. Interestingly, each time we passed through a squall, the winds on the other side seemed just a little bit stronger. By the time the clock read 1300, we were dealing with 25 knot sustained winds and no more squalls on the horizon. Conditions were sort of like an unending squall, though with good visibility.

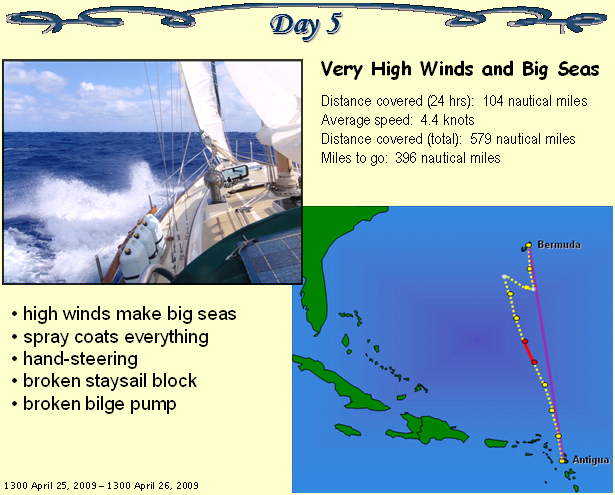

The continuous high winds (20-25 knots, with gusts over 30) caused the seas to build. Fortunately, with enough forward speed, Prudence does a great job of cutting through the waves. And, with this much wind, we were able to generate that speed with only the staysail and a single-reefed main.

Dancing through these waves causes a lot of spray in the air. Soon everything was coated with salt, including us. We started keeping the boards in the companionway in an effort to keep the salt-laden air from drifting down below. Still, it seemed, that via our own trips in and out the floor and all the surfaces we touched below became slick with salty residue.

Doing a 360-degree scan of the horizon takes longer now, because of the big waves. You have to time the scan of each section such that there aren't any nearby waves to blocking your view of the horizon. Then your progress is halted when the boat falls down into the valley between waves. You have to wait to get close to the top of the next wave to continue your scan.

It is amazing to watch and feel the boat move over these giant waves. For the most part they slide past and we simply go up and down. Sometimes, though, a wave will break at just the wrong time. If it hits the forward portion of the boat, the concussion sounds like a bomb has gone off and our speed will momentarily slow. If it hits the quarter, it can spin the back end in a sickening motion which leaves you wondering where your stomach wondered off to. In either case, a portion of the wave often lifts into the air and lands on deck and in the cockpit. Sitting under the dodger, we are saved from the soaking. The empty helm seat routinely gets splashed. Thank goodness for SUE.

As the day progressed, the conditions worsened. SUE was starting to whiplash the helm every time we fell off a steep wave. Concerned that something would eventually break, we switched to OTTO. His hydraulic arm keeps continuous pressure on the rudder post, stopping the dreaded whiplash action. We have plenty of power to run OTTO during daylight hours when the solar panels are generating juice, but we cannot keep him on all night. Our tricolor navigation light at the top of the mast is a true power hog (compared to all of the LED lighting we use elsewhere on the boat). We debated about adding another battery to the house bank while in Antigua, but the cost of their AGM batteries made us decide to forgo the luxury of more electrical storage capacity. We don't need it at anchor, and only rarely does the situation arise when we wish we had more power underway.

For the first time on this trip, we were going to have to steer the boat ourselves. Just as the sun was setting Sheryl took her position at the helm.

Only moments later, a loud bang was heard from the direction of the foredeck and a continuous 'whap-whap-whap' sound followed. The block from the staysail outhaul had broken.

I unclipped my tether from the cockpit and clipped it to the jackline, sliding it forward behind me as I went to secure the flapping sail. Fortunately, no damage (other than the destroyed block) had occurred. We dropped the sail and I tried once to re-rig something which would work for the night, but I couldn't get the foot of the sail tight enough. I lashed the sail with sail ties and would address the problem later, during daylight hours. It was a good thing this had happened before it became totally dark. Going forward in these conditions is scary enough as it is.