- PHOTOS:

- Dec 16, 2008 - May 21, 2009

- Mar 17, 2008 - Dec 15, 2008

- Nov 01, 2007 - Mar 16, 2008

- Our SC35 Sailboat: PRUDENCE

- SELECTED BLOGS

- Jan'05: The Idea

- May'05: First Cruise - Belize

- Aug'05: Buying Ashiya

- Oct'05: School in St. Vincent

- Nov'05: Ocracoke on Ashiya

- Jul'06: Long Trip on Ashiya

- Oct'06: Prudence Comes Home

- Nov'07: First Night Offshore

- Nov'07: Offshore Take Two

- Nov'07: Gulf Stream Crossing

- Dec'07: Green Turtle Cay

- Dec'07: Lynyard Cay

- Dec'07: Warderick Wells Cay

- Jan'08: George Town

- Jan'08: Life without a Fridge

- Jan'08: Mayaguana Island

- Jan'08: Turks & Caicos

- Jan'08: Dominican Republic

- Jan'08: Down the Waterfalls

- Feb'08: Puerto Rico

- Feb'08: Starter Troubles

- Feb'08: Vieques

- Mar'08: Finally Sailing Again

- Mar'08: Trip So Far

- Mar'08: Hiking Culebra

- Mar'08: Kayak & Snorkel I

- Mar'08: Teak and Waterspouts

- Mar'08: Kayak & Snorkel II

- Mar'08: Bottom Cleaning

- Apr'08: Culebra Social Life

- Apr'08: Culebra Routine

- Apr'08: Culebra Beaches

- Apr'08: Culebrita

- Jun'08: Kayak & Snorkel III

- Jun'08: Kayak & Snorkel IV

- Jun'08: Manta Ray

- Jun'08: Sea Turtles

- Jul'08: Cost of Cruising

- Jul'08: Busy Week in Culebra

- Jul'08: Getting to Land

- Jul'08: Leatherback Boil

- Jul'08: Fish and Volcano Dust

- Aug'08: Teaching Algebra

- Sep'08: Culebra Card Club

- Oct'08: Kayak & Snorkel V

- Oct'08: Prep for Hurricane

- Oct'08: Hurricane Omar

- Oct'08: Fish and Sea Glass

- Oct'08: Waterspouts

- Dec'08: Hurricane Season Ends

- Dec'08: Culebra to St. Martin

- Jan'09: Antigua Part 1

- Feb'09: The Saints

- Feb'09: Visiting Dominica

- Mar'09: Antigua Part 2

- Apr'09: Antigua to Bermuda

- May'09: Bermuda to Norfolk

- FULL LIST of Blog Entries

15 July 2009

14 July 2009

15 June 2009

14 June 2009 | Annapolis, MD

13 June 2009

12 June 2009

11 June 2009

10 June 2009 | Little Creek Marina, Norfolk, VA, USA

04 June 2009 | Little Creek Marina, Norfolk, VA, USA

31 May 2009 | Little Creek Marina, Norfolk, VA, USA

29 May 2009 | Little Creek Marina, Norfolk, VA, USA

26 May 2009 | Little Creek Marina, Norfolk, VA, USA

25 May 2009 | Little Creek Marina, Norfolk, VA, USA

13 May 2009 | through 21-May-2009

13 May 2009 | through 21-May-2009

12 May 2009 | St George's Town, Bermuda

11 May 2009 | St George's Town, Bermuda

07 May 2009 | St George's Town, Bermuda

04 May 2009 | St George's Town, Bermuda

21 April 2009 | through 02-May-2009

A Lesson in Sailing to Windward

01 March 2008 | Vieques to Culebra, Puerto Rico

CURRENT LOCATION: Anchored in Ensenada Honda, off the town of Dewey, on the island of Culebra, Puerto Rico

18 18.245' N, 065 17.867' W

When I sit down to write a blog entry, I realize that I am dealing with a varied audience. Some readers are sailors, some are even fellow cruisers, but many readers have little or no knowledge of sailing. For those who are uninitiated to the experience of sailing a boat to windward in big seas, I shall attempt to give you an impression of what it is like. For those who have had the grave misfortune of having to push a boat to your destination in this manner, you may tell me if I got it right.

First, take a good long look at the lead photo. This is what it looks like to sail to windward. Trying to explain how it feels is going to be a bit tougher. Imagine what it is like to stand on the side of a steep hill, with one foot higher than the other. Now walk around in a small semi-circle so that you are facing the opposite direction, and the other foot is higher. Continue to complete the circle, noting how your footing changes with each step and you have to focus on keeping your balance. Being on a sailboat which is bashing to windward is like that, except that you are standing still and trying to remain upright while the 'hill' is moving. Add to this motion both a howling wind which is blowing past your ears such that conversation with a person only 5 feet away is difficult and a continuous fine spray of salt water which occasionally comes at you as though tossed from a bucket, and you almost have it. All that is left to include is the thundering sound of dropping a 100-gallon water balloon from a second story window onto a concrete sidewalk every few seconds, and you are there.

All things considered, though, it is impossible for me to communicate exactly what it is like to be on a boat which is traveling in this manner unless you have experienced it firsthand. In addition, it is rather difficult to communicate the details of our trip from Vieques to Culebra without using a litany of sailing terminology. So, for those of you readers who are less familiar with the language of sailing, please enjoy the sentiment I relate below between the unfamiliar words. Better still, do a Google search on any words you don't know. It is highly likely that I will be using them over and over again in future blog entries.

We started our day before the sun rose. We were busy shaking reefs out of the mainsail and the staysail (reefing was done on the previous trip to make the sails smaller). Today, we intended to SAIL the boat and we wanted to be able to put up all the canvas at our disposal. At the first sign of light, we tossed off the mooring line and fell off into the very light wind (~5-7 knots). Please take note, dear Reader, that I said nothing about starting the engine. It was a blissfully quiet departure from Green Beach, Vieques.

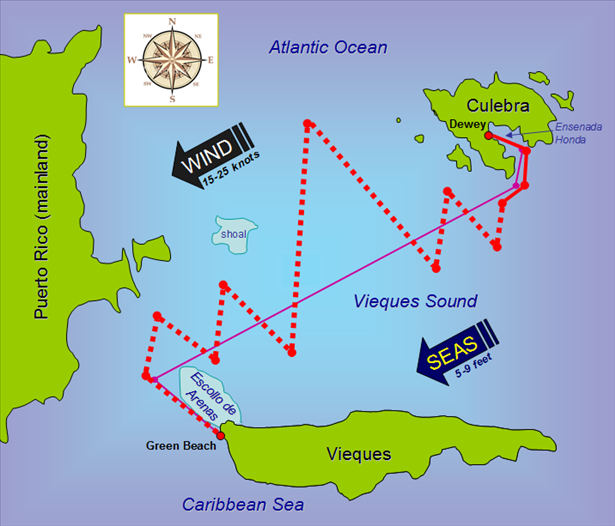

As you can see on the 'chart' below, our rhum line (shown in purple) was set to take us around an area called Escollo de Arenas. Since 'escollo' means trouble, and that is what we would be in if we tried to pass over these shoal waters, our path would divert us northwest for about 4 nautical miles before we turned to the northeast. The rhum line then runs 18 nautical miles to the southwest tip of Culebra, before finally turning us into the protected harbor of Ensenada Honda. Another 3 nautical miles would find us at anchor.

We finally got the boat moving in the light morning breeze which existed on the lee side of Vieques; however, once we got clear of land the winds rapidly picked up. For the first time since we left the Bahamas, we were on a beautiful beam reach. And, with winds picking up quickly to 18-knots, we were flying across the water at 7 knots or better. That is about as fast as our boat can travel through the water. It was absolutely exhilarating! It ended the moment we rounded Escollo de Arenas.

Since we had decided to sail, rather than motorsail, there was no way we could travel along the purple rhum line. The rhum line took us directly into the wind. Under sail alone, we can angle the boat only as close as 50 degrees to the wind. Any closer, and our sails start flapping and the boat comes to a stop. In addition to having to angle the boat so far from where we want to go, the waves and current we were facing have a nasty tendency to push the boat way from that path even farther.

Hence, you can see the red dotted-line path we took across Vieques Sound. Each change in direction, or tack, is accompanied by a flurry of activity. The helmsman must make the decision that a tack should take place (often with the help of opinions to that effect from the crew). The helmsman will shout the order, "Prepare to tack!" When sailing close-hauled, as we were the entire way across the sound, the main chore for the crew is to get the genoa across to the other side. Upon hearing the command from the helmsman, crew of Prudence readies the sheets (lines) for the genoa to come across. When the helmsman observes that the crew is ready, a confirmation is requested, "Ready to tack?" If, in fact they are ready, the crew responds, "Ready." The helmsman then falls off a bit in order to build up speed and looks for a good opening in the wave pattern for turning the boat. One doesn't want to hit a wave and stop the boat in the middle of this turn.

Once a suitable speed is obtained and an opening is spotted, the helmsman gives the notification, "Hard alee," and the bow of the boat is turned hard through the wind. The crew waits until the genoa flogs, then releases the sheet, pulling in on the opposite sheet. As the bow passes through the wind, the wind now helps to push the genoa through the space between the forestay and the innerstay (upon which our staysail is flown). Once it bursts through to the other side, it flaps loudly until the crew can put tension on that sheet, first pulling in by hand, then tensioning with the winch. It takes quite a few cranks on the winch handle to get the genoa in tight when one is sailing close-hauled. Meanwhile, the helmsman concentrates on getting the boat up-to-speed and as close as possible to the wind.

The crew, now breathing heavily from the exertion, will check to see if the staysail tended itself properly over to the other side. If not, a little manipulation of the sheet will usually coax the staysail boom to the correct position. Together, the helmsman and the crew will make adjustments to the position of the main by moving the car of the traveler. With our staysail funneling wind along the centerline, we can get slightly better performance from the main by shifting the traveler car slightly to windward of the centerline. Close-hauled sailing in big winds generally requires us both to manipulate the main due to the incredible amount of force at play.

The crew is now free to help watch the water for floating debris and other boat traffic, make notes of position in the log book and on the chart, and offer suggestions to the helmsman. The helmsman is free, in turn, to either heed or ignore the advice of the crew in their efforts to keep the boat speed up while keeping as close to the wind as possible (a delicate balancing act, I can assure you). Since the waves on the sound were often confused (bordering on chaotic), we opted to hand-steer on this day, rather than deploy our windvane steering, SUE.

After seven hours of being heeled over on alternate sides, with both toerails

spending plenty of time in the water, and pitching through the closely spaced waves, we finally closed-in upon our destination. The engine was turned on about one and a half nautical miles from land, and the solid red line shows the path we motored into Ensenada Honda. My 'chart' shows this as being deceptively easy, largely because I did not include the coral reefs.

The entry to Ensenada Honda is relatively small and fringed by coral reefs. The entrance is well marked, but the approach is one which will set your heart to beating at a rapid pace. We were motorsailing directly to windward with a full main and full staysail in 20+ knot winds and big seas as we approached the red and green buoys just off to our port side. Immediately on either side of each buoy waves were crashing on the reefs. It was a sight which brought fear to my heart and focused my mind. Our biggest decision at this point was how long we should keep up the mainsail.

Once we turned off of the wind, the main would provide a lot of power and move us to the entrance rather fast, perhaps too fast. On the other hand, although one does not even like to think about it, keeping the main up is a safety measure (just in case the engine fails). In theory, the main will provide enough power to keep the boat moving and give you steerage in this undesirable scenario. Our staysail can serve the same function, only with slightly less power delivered, which is good for a controlled entry and, hopefully would be sufficient in the unfortunate event of engine difficulties.

We kept the main up until we were about to turn off the wind and were poised to drop it when we were hailed on the radio, "Prudence, Prudence, Prudence, this is *****, over." (Note: I have elected to keep the name of the hailing vessel anonymous) Our friends on s/v ***** were anchored just inside the reef and happened to recognize us on our approach. Unfortunately, they could not have picked a worse time to interrupt us. Sheryl answered, thinking that they may have some valuable 'local knowledge' to which we should be privy, prior to entering.

As she was trying to make contact, we rapidly began to approach the spot for our turn. With reefs to one side, shoals to the other, and 3 large power boats approaching the entrance at planing speed, I began to get a bit nervous about having the full main up in these strong winds. Fortunately, I suppose, someone else 'stepped' on the transmission (speaking loudly and rapidly in Spanish) and Sheryl had to abandon the radio. We dropped the main and motored through the cut between the buoys with a little help from the staysail. We will never know if there was some local wisdom that we missed, because when s/v***** hailed again we simply exchanged information about sailing plans (they were off to St. Thomas in the morning).

We motored past them, bound for the anchorage at the northern end of Ensenada Honda, off the town of Dewey. We set our anchor in 25-feet of water, relatively close to the town dock. The position should serve us well as we prepare for guests later this month.

Our journey had taken a total of 10 hours, from slipping the mooring line to putting down the anchor, and had required nearly as many tacks. A mere 14% of that time was spent under motor (much better than our nearly 100% average, of late). However, in order to cover a rhum line distance of 25 nautical miles, we had to push our keel through 40 nautical miles of water. We were both well shaken and tired, but a with a new town to explore, only a few feet away across the water, we were motivated to action.

We dug Patience out of the sail locker and, after cleaning, assembling, and inflating, we added the Evinrude and puttered over to town. We bypassed the town dock in favor of the Dinghy Dock Bar & Restaurant. We were hungry, but it was only 5PM and the restaurant did not open until 6:30. We had a drink at the bar, watching Prudence to be certain that she stayed put. When we were finally relaxed with liquid libation and comfortable that the winds were settling and Prudence was going nowhere, we took a quick walk around town.

We checked out the two grocery stores and looked at the menu of a few restaurants. From what we have seen, there will be very little dining out for us in this town (at least at dinner time). The prices were a bit high for our liking (dinner for two would likely cost $30-40, without including any drinks). We can eat for a week (or at least a few days) on what that would purchase in the grocery stores, so we returned to the boat in the waning twilight to enjoy a delicious dinner direct from the galley.

Sleep soon followed, as we enjoyed the comfort of a smooth anchorage for the first time since Salinas (both Puerto Patillas and Green Beach presented a modicum of rolliness throughout the nighttime hours). I think we will be quite happy here, enjoying a bit of a vacation from moving the boat while we await the arrival of some familiar faces from stateside.

18 18.245' N, 065 17.867' W

When I sit down to write a blog entry, I realize that I am dealing with a varied audience. Some readers are sailors, some are even fellow cruisers, but many readers have little or no knowledge of sailing. For those who are uninitiated to the experience of sailing a boat to windward in big seas, I shall attempt to give you an impression of what it is like. For those who have had the grave misfortune of having to push a boat to your destination in this manner, you may tell me if I got it right.

First, take a good long look at the lead photo. This is what it looks like to sail to windward. Trying to explain how it feels is going to be a bit tougher. Imagine what it is like to stand on the side of a steep hill, with one foot higher than the other. Now walk around in a small semi-circle so that you are facing the opposite direction, and the other foot is higher. Continue to complete the circle, noting how your footing changes with each step and you have to focus on keeping your balance. Being on a sailboat which is bashing to windward is like that, except that you are standing still and trying to remain upright while the 'hill' is moving. Add to this motion both a howling wind which is blowing past your ears such that conversation with a person only 5 feet away is difficult and a continuous fine spray of salt water which occasionally comes at you as though tossed from a bucket, and you almost have it. All that is left to include is the thundering sound of dropping a 100-gallon water balloon from a second story window onto a concrete sidewalk every few seconds, and you are there.

All things considered, though, it is impossible for me to communicate exactly what it is like to be on a boat which is traveling in this manner unless you have experienced it firsthand. In addition, it is rather difficult to communicate the details of our trip from Vieques to Culebra without using a litany of sailing terminology. So, for those of you readers who are less familiar with the language of sailing, please enjoy the sentiment I relate below between the unfamiliar words. Better still, do a Google search on any words you don't know. It is highly likely that I will be using them over and over again in future blog entries.

We started our day before the sun rose. We were busy shaking reefs out of the mainsail and the staysail (reefing was done on the previous trip to make the sails smaller). Today, we intended to SAIL the boat and we wanted to be able to put up all the canvas at our disposal. At the first sign of light, we tossed off the mooring line and fell off into the very light wind (~5-7 knots). Please take note, dear Reader, that I said nothing about starting the engine. It was a blissfully quiet departure from Green Beach, Vieques.

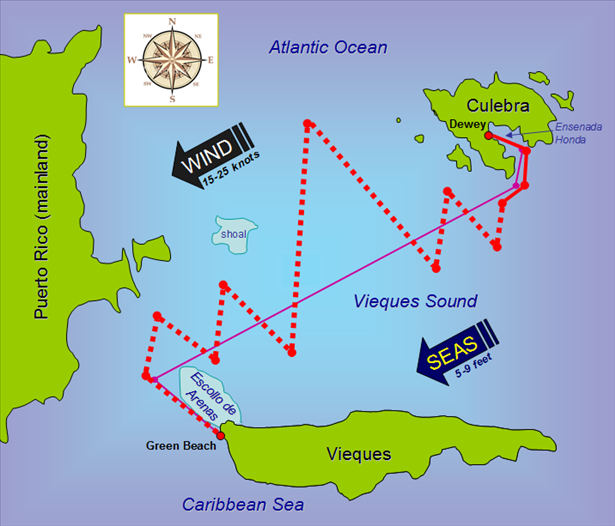

As you can see on the 'chart' below, our rhum line (shown in purple) was set to take us around an area called Escollo de Arenas. Since 'escollo' means trouble, and that is what we would be in if we tried to pass over these shoal waters, our path would divert us northwest for about 4 nautical miles before we turned to the northeast. The rhum line then runs 18 nautical miles to the southwest tip of Culebra, before finally turning us into the protected harbor of Ensenada Honda. Another 3 nautical miles would find us at anchor.

We finally got the boat moving in the light morning breeze which existed on the lee side of Vieques; however, once we got clear of land the winds rapidly picked up. For the first time since we left the Bahamas, we were on a beautiful beam reach. And, with winds picking up quickly to 18-knots, we were flying across the water at 7 knots or better. That is about as fast as our boat can travel through the water. It was absolutely exhilarating! It ended the moment we rounded Escollo de Arenas.

Since we had decided to sail, rather than motorsail, there was no way we could travel along the purple rhum line. The rhum line took us directly into the wind. Under sail alone, we can angle the boat only as close as 50 degrees to the wind. Any closer, and our sails start flapping and the boat comes to a stop. In addition to having to angle the boat so far from where we want to go, the waves and current we were facing have a nasty tendency to push the boat way from that path even farther.

Hence, you can see the red dotted-line path we took across Vieques Sound. Each change in direction, or tack, is accompanied by a flurry of activity. The helmsman must make the decision that a tack should take place (often with the help of opinions to that effect from the crew). The helmsman will shout the order, "Prepare to tack!" When sailing close-hauled, as we were the entire way across the sound, the main chore for the crew is to get the genoa across to the other side. Upon hearing the command from the helmsman, crew of Prudence readies the sheets (lines) for the genoa to come across. When the helmsman observes that the crew is ready, a confirmation is requested, "Ready to tack?" If, in fact they are ready, the crew responds, "Ready." The helmsman then falls off a bit in order to build up speed and looks for a good opening in the wave pattern for turning the boat. One doesn't want to hit a wave and stop the boat in the middle of this turn.

Once a suitable speed is obtained and an opening is spotted, the helmsman gives the notification, "Hard alee," and the bow of the boat is turned hard through the wind. The crew waits until the genoa flogs, then releases the sheet, pulling in on the opposite sheet. As the bow passes through the wind, the wind now helps to push the genoa through the space between the forestay and the innerstay (upon which our staysail is flown). Once it bursts through to the other side, it flaps loudly until the crew can put tension on that sheet, first pulling in by hand, then tensioning with the winch. It takes quite a few cranks on the winch handle to get the genoa in tight when one is sailing close-hauled. Meanwhile, the helmsman concentrates on getting the boat up-to-speed and as close as possible to the wind.

The crew, now breathing heavily from the exertion, will check to see if the staysail tended itself properly over to the other side. If not, a little manipulation of the sheet will usually coax the staysail boom to the correct position. Together, the helmsman and the crew will make adjustments to the position of the main by moving the car of the traveler. With our staysail funneling wind along the centerline, we can get slightly better performance from the main by shifting the traveler car slightly to windward of the centerline. Close-hauled sailing in big winds generally requires us both to manipulate the main due to the incredible amount of force at play.

The crew is now free to help watch the water for floating debris and other boat traffic, make notes of position in the log book and on the chart, and offer suggestions to the helmsman. The helmsman is free, in turn, to either heed or ignore the advice of the crew in their efforts to keep the boat speed up while keeping as close to the wind as possible (a delicate balancing act, I can assure you). Since the waves on the sound were often confused (bordering on chaotic), we opted to hand-steer on this day, rather than deploy our windvane steering, SUE.

After seven hours of being heeled over on alternate sides, with both toerails

spending plenty of time in the water, and pitching through the closely spaced waves, we finally closed-in upon our destination. The engine was turned on about one and a half nautical miles from land, and the solid red line shows the path we motored into Ensenada Honda. My 'chart' shows this as being deceptively easy, largely because I did not include the coral reefs.

The entry to Ensenada Honda is relatively small and fringed by coral reefs. The entrance is well marked, but the approach is one which will set your heart to beating at a rapid pace. We were motorsailing directly to windward with a full main and full staysail in 20+ knot winds and big seas as we approached the red and green buoys just off to our port side. Immediately on either side of each buoy waves were crashing on the reefs. It was a sight which brought fear to my heart and focused my mind. Our biggest decision at this point was how long we should keep up the mainsail.

Once we turned off of the wind, the main would provide a lot of power and move us to the entrance rather fast, perhaps too fast. On the other hand, although one does not even like to think about it, keeping the main up is a safety measure (just in case the engine fails). In theory, the main will provide enough power to keep the boat moving and give you steerage in this undesirable scenario. Our staysail can serve the same function, only with slightly less power delivered, which is good for a controlled entry and, hopefully would be sufficient in the unfortunate event of engine difficulties.

We kept the main up until we were about to turn off the wind and were poised to drop it when we were hailed on the radio, "Prudence, Prudence, Prudence, this is *****, over." (Note: I have elected to keep the name of the hailing vessel anonymous) Our friends on s/v ***** were anchored just inside the reef and happened to recognize us on our approach. Unfortunately, they could not have picked a worse time to interrupt us. Sheryl answered, thinking that they may have some valuable 'local knowledge' to which we should be privy, prior to entering.

As she was trying to make contact, we rapidly began to approach the spot for our turn. With reefs to one side, shoals to the other, and 3 large power boats approaching the entrance at planing speed, I began to get a bit nervous about having the full main up in these strong winds. Fortunately, I suppose, someone else 'stepped' on the transmission (speaking loudly and rapidly in Spanish) and Sheryl had to abandon the radio. We dropped the main and motored through the cut between the buoys with a little help from the staysail. We will never know if there was some local wisdom that we missed, because when s/v***** hailed again we simply exchanged information about sailing plans (they were off to St. Thomas in the morning).

We motored past them, bound for the anchorage at the northern end of Ensenada Honda, off the town of Dewey. We set our anchor in 25-feet of water, relatively close to the town dock. The position should serve us well as we prepare for guests later this month.

Our journey had taken a total of 10 hours, from slipping the mooring line to putting down the anchor, and had required nearly as many tacks. A mere 14% of that time was spent under motor (much better than our nearly 100% average, of late). However, in order to cover a rhum line distance of 25 nautical miles, we had to push our keel through 40 nautical miles of water. We were both well shaken and tired, but a with a new town to explore, only a few feet away across the water, we were motivated to action.

We dug Patience out of the sail locker and, after cleaning, assembling, and inflating, we added the Evinrude and puttered over to town. We bypassed the town dock in favor of the Dinghy Dock Bar & Restaurant. We were hungry, but it was only 5PM and the restaurant did not open until 6:30. We had a drink at the bar, watching Prudence to be certain that she stayed put. When we were finally relaxed with liquid libation and comfortable that the winds were settling and Prudence was going nowhere, we took a quick walk around town.

We checked out the two grocery stores and looked at the menu of a few restaurants. From what we have seen, there will be very little dining out for us in this town (at least at dinner time). The prices were a bit high for our liking (dinner for two would likely cost $30-40, without including any drinks). We can eat for a week (or at least a few days) on what that would purchase in the grocery stores, so we returned to the boat in the waning twilight to enjoy a delicious dinner direct from the galley.

Sleep soon followed, as we enjoyed the comfort of a smooth anchorage for the first time since Salinas (both Puerto Patillas and Green Beach presented a modicum of rolliness throughout the nighttime hours). I think we will be quite happy here, enjoying a bit of a vacation from moving the boat while we await the arrival of some familiar faces from stateside.

| Vessel Name: | Prudence |

| About: |

Gallery not available

- PHOTOS:

- Dec 16, 2008 - May 21, 2009

- Mar 17, 2008 - Dec 15, 2008

- Nov 01, 2007 - Mar 16, 2008

- Our SC35 Sailboat: PRUDENCE

- SELECTED BLOGS

- Jan'05: The Idea

- May'05: First Cruise - Belize

- Aug'05: Buying Ashiya

- Oct'05: School in St. Vincent

- Nov'05: Ocracoke on Ashiya

- Jul'06: Long Trip on Ashiya

- Oct'06: Prudence Comes Home

- Nov'07: First Night Offshore

- Nov'07: Offshore Take Two

- Nov'07: Gulf Stream Crossing

- Dec'07: Green Turtle Cay

- Dec'07: Lynyard Cay

- Dec'07: Warderick Wells Cay

- Jan'08: George Town

- Jan'08: Life without a Fridge

- Jan'08: Mayaguana Island

- Jan'08: Turks & Caicos

- Jan'08: Dominican Republic

- Jan'08: Down the Waterfalls

- Feb'08: Puerto Rico

- Feb'08: Starter Troubles

- Feb'08: Vieques

- Mar'08: Finally Sailing Again

- Mar'08: Trip So Far

- Mar'08: Hiking Culebra

- Mar'08: Kayak & Snorkel I

- Mar'08: Teak and Waterspouts

- Mar'08: Kayak & Snorkel II

- Mar'08: Bottom Cleaning

- Apr'08: Culebra Social Life

- Apr'08: Culebra Routine

- Apr'08: Culebra Beaches

- Apr'08: Culebrita

- Jun'08: Kayak & Snorkel III

- Jun'08: Kayak & Snorkel IV

- Jun'08: Manta Ray

- Jun'08: Sea Turtles

- Jul'08: Cost of Cruising

- Jul'08: Busy Week in Culebra

- Jul'08: Getting to Land

- Jul'08: Leatherback Boil

- Jul'08: Fish and Volcano Dust

- Aug'08: Teaching Algebra

- Sep'08: Culebra Card Club

- Oct'08: Kayak & Snorkel V

- Oct'08: Prep for Hurricane

- Oct'08: Hurricane Omar

- Oct'08: Fish and Sea Glass

- Oct'08: Waterspouts

- Dec'08: Hurricane Season Ends

- Dec'08: Culebra to St. Martin

- Jan'09: Antigua Part 1

- Feb'09: The Saints

- Feb'09: Visiting Dominica

- Mar'09: Antigua Part 2

- Apr'09: Antigua to Bermuda

- May'09: Bermuda to Norfolk

- FULL LIST of Blog Entries