- PHOTOS:

- Dec 16, 2008 - May 21, 2009

- Mar 17, 2008 - Dec 15, 2008

- Nov 01, 2007 - Mar 16, 2008

- Our SC35 Sailboat: PRUDENCE

- SELECTED BLOGS

- Jan'05: The Idea

- May'05: First Cruise - Belize

- Aug'05: Buying Ashiya

- Oct'05: School in St. Vincent

- Nov'05: Ocracoke on Ashiya

- Jul'06: Long Trip on Ashiya

- Oct'06: Prudence Comes Home

- Nov'07: First Night Offshore

- Nov'07: Offshore Take Two

- Nov'07: Gulf Stream Crossing

- Dec'07: Green Turtle Cay

- Dec'07: Lynyard Cay

- Dec'07: Warderick Wells Cay

- Jan'08: George Town

- Jan'08: Life without a Fridge

- Jan'08: Mayaguana Island

- Jan'08: Turks & Caicos

- Jan'08: Dominican Republic

- Jan'08: Down the Waterfalls

- Feb'08: Puerto Rico

- Feb'08: Starter Troubles

- Feb'08: Vieques

- Mar'08: Finally Sailing Again

- Mar'08: Trip So Far

- Mar'08: Hiking Culebra

- Mar'08: Kayak & Snorkel I

- Mar'08: Teak and Waterspouts

- Mar'08: Kayak & Snorkel II

- Mar'08: Bottom Cleaning

- Apr'08: Culebra Social Life

- Apr'08: Culebra Routine

- Apr'08: Culebra Beaches

- Apr'08: Culebrita

- Jun'08: Kayak & Snorkel III

- Jun'08: Kayak & Snorkel IV

- Jun'08: Manta Ray

- Jun'08: Sea Turtles

- Jul'08: Cost of Cruising

- Jul'08: Busy Week in Culebra

- Jul'08: Getting to Land

- Jul'08: Leatherback Boil

- Jul'08: Fish and Volcano Dust

- Aug'08: Teaching Algebra

- Sep'08: Culebra Card Club

- Oct'08: Kayak & Snorkel V

- Oct'08: Prep for Hurricane

- Oct'08: Hurricane Omar

- Oct'08: Fish and Sea Glass

- Oct'08: Waterspouts

- Dec'08: Hurricane Season Ends

- Dec'08: Culebra to St. Martin

- Jan'09: Antigua Part 1

- Feb'09: The Saints

- Feb'09: Visiting Dominica

- Mar'09: Antigua Part 2

- Apr'09: Antigua to Bermuda

- May'09: Bermuda to Norfolk

- FULL LIST of Blog Entries

15 July 2009

14 July 2009

15 June 2009

14 June 2009 | Annapolis, MD

13 June 2009

12 June 2009

11 June 2009

10 June 2009 | Little Creek Marina, Norfolk, VA, USA

04 June 2009 | Little Creek Marina, Norfolk, VA, USA

31 May 2009 | Little Creek Marina, Norfolk, VA, USA

29 May 2009 | Little Creek Marina, Norfolk, VA, USA

26 May 2009 | Little Creek Marina, Norfolk, VA, USA

25 May 2009 | Little Creek Marina, Norfolk, VA, USA

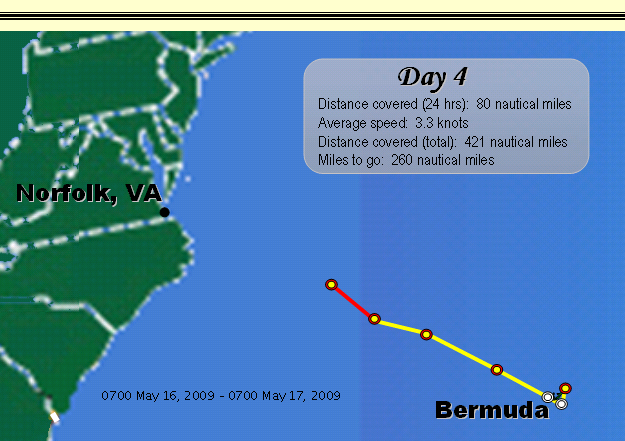

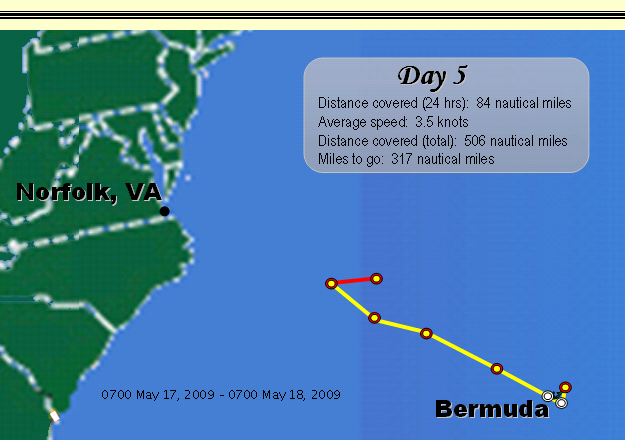

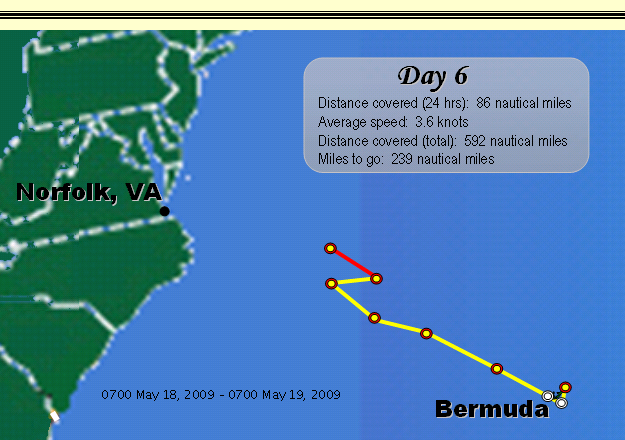

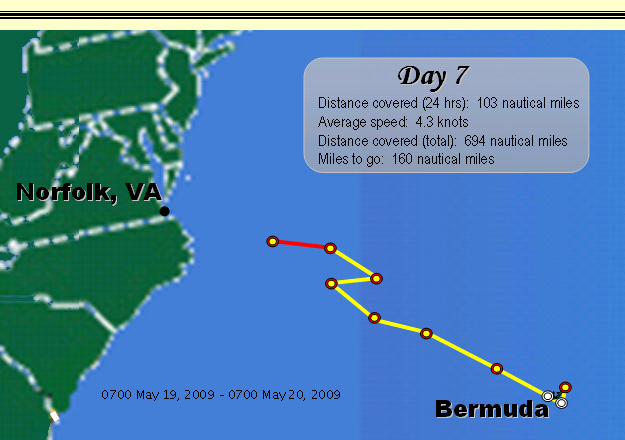

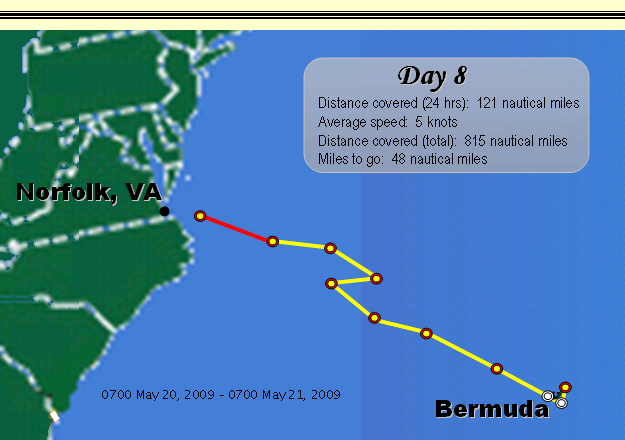

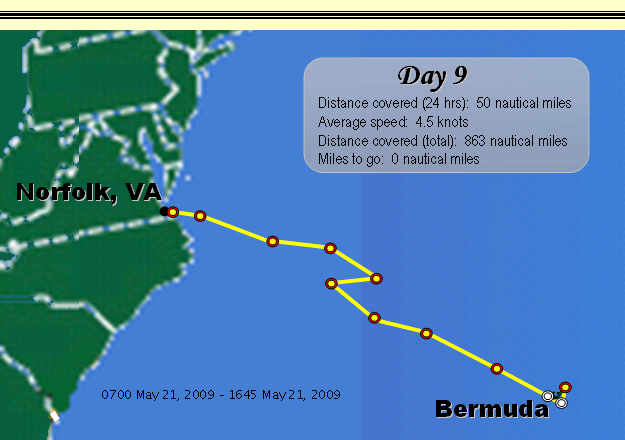

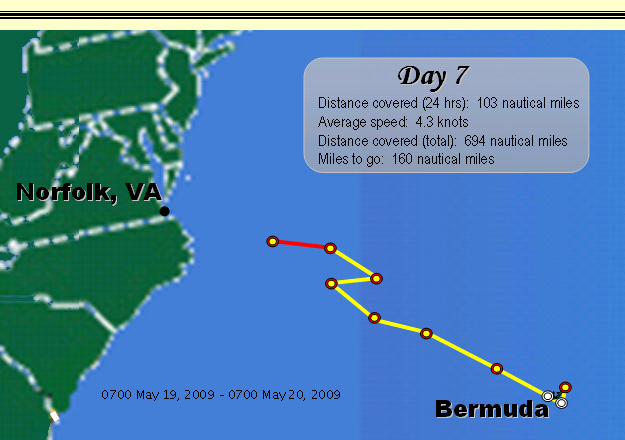

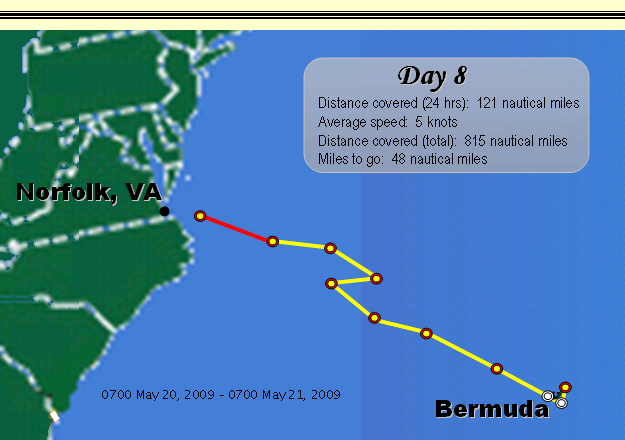

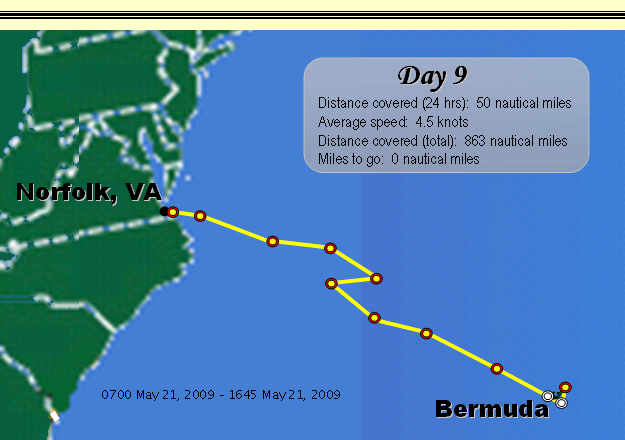

13 May 2009 | through 21-May-2009

13 May 2009 | through 21-May-2009

12 May 2009 | St George's Town, Bermuda

11 May 2009 | St George's Town, Bermuda

07 May 2009 | St George's Town, Bermuda

04 May 2009 | St George's Town, Bermuda

21 April 2009 | through 02-May-2009

Passage from Bermuda to Norfolk: Part 1

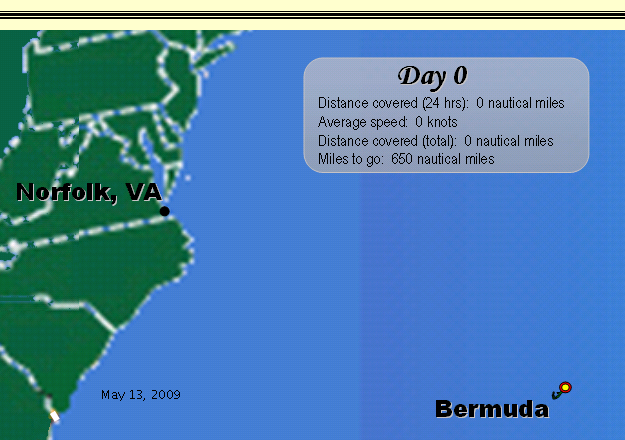

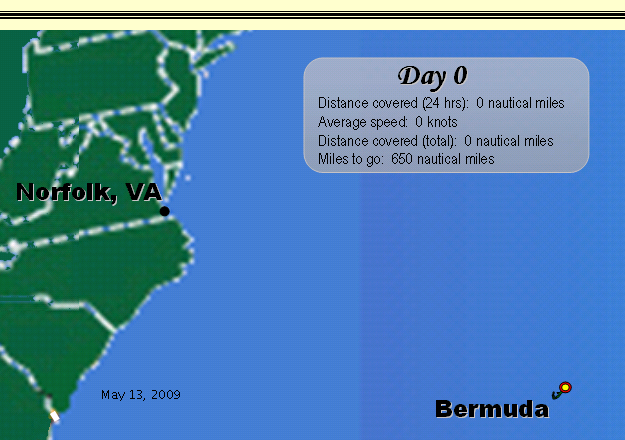

13 May 2009 | through 21-May-2009

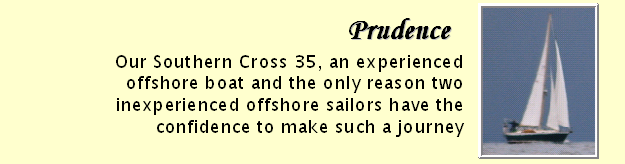

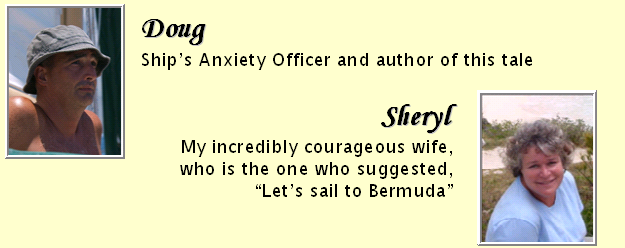

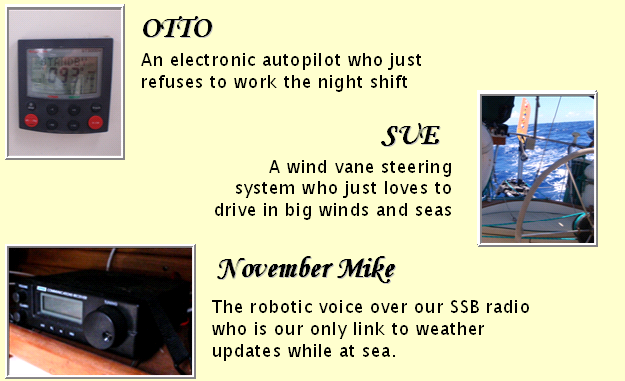

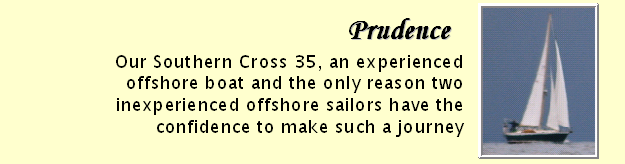

This is the story of a journey from Bermuda to Norfolk on a 35-foot sailboat. Characters and crew aboard were:

The Race is about to begin. The competitive nature of the journey between the east coast of the United States and Bermuda under sail has a rich history, or so I have heard. Not being an aficionado of sailboat racing (or any sort of racing, for that matter), I draw that conclusion from what I have stumbled across in my reading of sailing magazines over these past few years.

I would pick up a copy of SAIL magazine and rapidly skip past any of the articles describing tips and tricks to help you win your next local event on the water, in favor of an article describing the dire circumstances of some casual sailors. One article I recall described a fellow out for a day sail who tucked down below to discover the floorboard hatches to the bilge were floating (a loosened stuffing box turned out to be the cause), or another where a couple on a boat just off a dock suddenly lost steerage because a long handled scrubby brush had become entangled in the cable to the steering quadrant. These articles always ended with a 'Lessons Learned' section which I found most enlightening. Better I learn from their mistakes than make them myself. On the counter end of the educational motivation spectrum, though, I had little time and energy for cataloging the details for wringing that extra half-knot of speed out of my boat. Too bad, for it may have been of some use to me on this particular trip.

This Race, of our own design, is a direct product of our selection of weather windows. We will not be facing any other boats in this challenge, instead we will be up against Mother Nature herself. Our long-term weather outlook shows a fairly strong cold front will pass off the coast just as we are arriving at the Gulf Stream. With this type of passing weather system, winds generally go from southwesterly to northerly in very rapid succession, and this one was predicted to be no exception to that rule. Our task is to get the boat past the Gulf Stream before the winds switch to a northerly direction. The Stream flows north, and the circumstance of wind against current is to be avoided at all costs. It causes large square-shaped waves. Not good for folks on a small boat.

The timing is such that we need to maintain a 5-knot overall average to cross the Stream before doomsday on Monday. This is certainly doable, but will require steady winds from the right direction. And, based on our analysis, winds should stay better than 10 knots (more often in the realm of 15-20) ranging anywhere from northeast to southwest, which is perfect for our northwesterly course.

So, with anxiety mounting, we make the commitment to depart by checking out with Customs and Immigration on Tuesday afternoon. Aboard Patience, Sheryl battled some big, pointy waves in the harbor which have been stirred up by two days of strong southwesterly winds. She presented herself with papers for departure in hand and, perhaps prompted by her somewhat sodden appearance, the officials asked, "Have you checked the weather forecast?" There is nothing quite as effective as that particular question to squash your confidence and make you doubt your decision. To her credit, Sheryl didn't tell me about that exchange until several days into our journey. No need to add to my already monumental anxiety. She simply responded to their inquiry in the affirmative and went on about the business of making our departure from Bermuda official.

The forecast had called for a decrease in wind strength and a shift to the north this evening. These are the conditions under which we wished to depart. Unfortunately, there was no sign of those conditions when Sheryl returned from her final Bermudian errands. I balanced aboard the dinghy on sharp waves as I lifted the outboard engine up to Sheryl who was standing ready at the stern rail mount. Just as we were hauling the dinghy from the water, the chop in the harbor began to subside. By the time I had the dinghy stowed and the cockpit locker completely repacked (a process which takes about an hour), the water surrounding the boat had become a mill pond.

As darkness descended upon us, a gentle wind pushed us around our anchor until the bow was pointing north. We both breathed a heavy sigh of relief. We briefly considered a nighttime departure, which would give us a 9-hour edge in the Race, but a quick look at the chart and all the shallow reefs surrounding the islands of Bermuda was all it took to put that idea to rest. Speaking of rest, we savored the final evening of togetherness and uninterrupted sleep. At least as much as our nervousness regarding the nautical miles before us would allow.

First light on Wednesday morning brought with it the welcome sound of several other anchor chains being returned to their respective lockers. We did not know where these other boats were bound for, but we took solace in the fact that others obviously concurred with our opinion that this was a good day to be under way. The mere sight of others getting the jump on us, so to speak, spurred us to action even more quickly than our own eagerness to begin the Race otherwise would have.

We quickly rearranged the boat into our version of 'offshore-mode', and started the engine. While I removed the snubber from the anchor rode, Sheryl called Bermuda Harbour Radio on the VHF and requested permission to navigate the Town Cut. A light drizzle began to fall. We received the O.K. to exit the harbor and I labored to lift our chain and anchor aboard. I was drenched with sweat within my foul weather gear and with rain on the exterior as I returned to the cockpit. Sheryl later indicated that the sight of me brought to mind the proverbial drowned rodent.

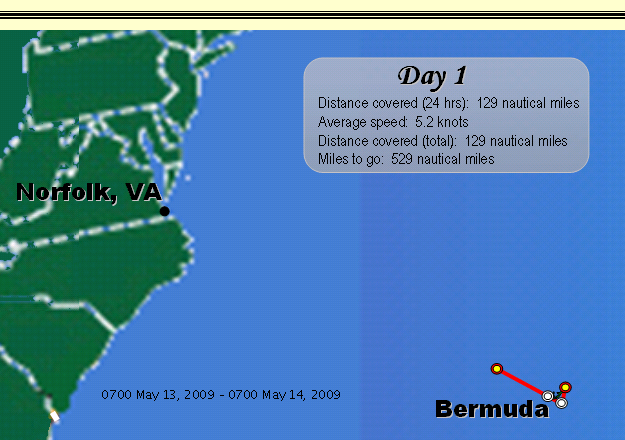

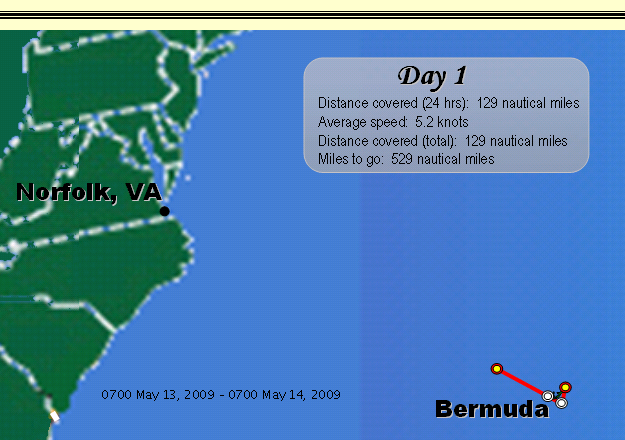

By approximately 7AM, we were out through the Town Cut and rounding the SPIT buoy. Therefore, we decided to measure each of our days on this trip with the start/end time of Oh-700. This day was turning out to be a fine day for sailing, but less than agreeable from other weather perspectives. It was drizzling and somewhat foggy (although visibility was such that we could still clearly spot a cruise ship over 2-nautical miles ahead, thank goodness). Eventually, the rain ceased, but the cockpit and its inhabitants remained damp under a sky which was a solid blanket of grey clouds.

The engine was silenced within an hour of its start time, and we struggled to find the correct sail arrangement for the conditions. As we navigated a semi-circle around the southwest corner of Bermuda, we surmised that land effects were the likely culprits causing these variable winds. Just a few more hours and we wouldn't have to worry about those pesky land effects again for several days.

Early afternoon found us on a rhumb line which extended over 600 nautical miles to Norfolk. But our focus was on a region of the Atlantic that was slightly over 100 nautical miles closer, the Gulf Stream, our finish line for the Race. Once we were on the rhumb line, we made good progress toward our destination. Despite this fact, my anxiety was at an all time high. I had to make a very conscious effort not to clench my teeth, a nervous habit of mine. My dentist has suggested that the pressure is causing tiny stress fractures to form in my precious pearly whites (and that was before we left to go cruising). Try as I might, I still occasionally discover my chompers mashed together without my even knowing it. Due to this dreadful habit, my teeth actually ached for three days after our arrival in Bermuda.

Late in the day I started noticing the first signs of seasickness. Unfamiliar to me until just a few weeks ago (at the start of our previous passage), the nausea, headache and general malaise settled in even before nightfall. I suppose that my body has learned this response to the motion of the ocean supplied in combination with the elevated adrenaline which accompanies a perpetual state of anxiety. I took some of Sheryl's medication to help me cope (seasickness meds not anti-anxiety drugs, although some valium would have been warranted).

Strangely enough, reading, for me, helps to relieve the symptoms of seasickness. For Sheryl, it is an activity which can only be pursued once such symptoms have subsided. Perhaps it is the escapist nature of losing myself in a book which transports me away from the stresses (both physical and mental) of my surroundings that allows this modicum of relief. Regardless, I am grateful.

I spent my downtime in the cozy sleeping settee in the salon, which we have dubbed the Nest, enjoying a book by Bill Bryson (one of my favorite authors). Sheryl spied this gem in a book exchange at the visitor's information center in St. George's Town. For a time, I am not on a boat in the Atlantic, I am in England with Bill. When on watch, I continue to read but with frequent interruptions which tend to make the escape more difficult. I let SUE steer the boat while I am reminded by my new kitchen timer to check the horizon for boat traffic approximately every 10 minutes.

The onset of darkness brings an end to my reading while on watch, but the kitchen timer continues to aid the regularity of my horizon scans. When I purchased this item in Bermuda, I elected to go with the old fashioned spring mechanism over an electronic timer, largely for the sake of it holding up to a potential dousing with salt water (it only has to last this one trip, then I will be through with long passages forever). The downside to this non-electric gizmo is the lack of any lighting. I cannot see where the 10-minute mark is when I twist it in the dark.

Initially, used the red LED flashlight we keep in the cockpit to illuminate the dial, but quickly learned to simply listen to the subtle clicks made by the clockwork mechanism as I twisted. Six clicks was equal to 10 minutes. So, I spent the first of many dark 3-hour shifts to come as follows: click ... click ... click ... click ... click ... click ... wait ... ding ... standup ... turn a 360-degree pirouette while looking at the horizon for any signs of light... turn back the other way in order to unwrap your safety harness tether (double checking for any lights) ... sit back down ... and repeat.

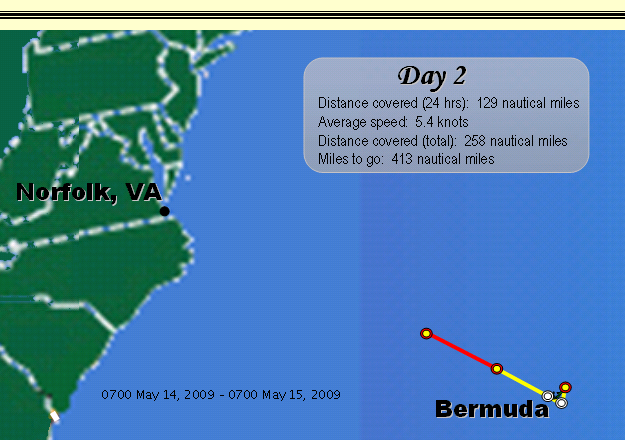

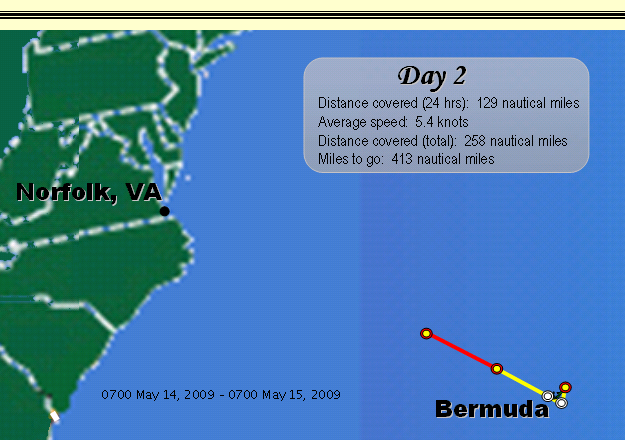

It was obvious from the start that this day would be much sunnier than the last. Despite the good general weather conditions, we were having trouble adapting to the sailing conditions. The winds had shifted around to our stern and were forcing us to run in order to maintain course and speed along our rhumb line. Although we had the good fortune while in the tropics to experience an occasional broad reach, by and large the wind was always forward of the beam. This was the first time for us to attempt to run before the wind in a long, long time.

When the wind is behind you, the sailing experience is entirely different. The wind you are creating by moving forward is subtracted from the actual wind, meaning that much greater speeds are realized with lower apparent wind. Although you may be going 5 to 6 knots, you do not feel the wind on your face as you do when sailing close hauled or on a reach. Initially, we tried to go wing-on-wing. This had worked wonders for us back in the Neuse River. Unfortunately, ocean swell and running wing-on-wing in light air are mutually exclusive. No matter how I tried, waves would kick us around and cause one or the other sail to flog or back.

With winds becoming lighter, we discussed the option of digging our cruising spinnaker out of the cockpit locker, and were eventually driven to it by the incessant flapping of the genoa as we fell off of waves. I don't know whether it was the residual seasickness or the fact that I simply had not yet found my sea legs, but as I took the bag containing this big sail forward I knew something just didn't feel right.

The cruising spinnaker is a large sail made of very light material. Ours is contained within a sock. You lift the sock into place first, then raise sock to deploy the sail. As I dug this long, crinkling snake out of its bag, it spilled across the foredeck. Once underfoot, the material is as slippery as grease making the process of untangling the lines in a rolly seaway a difficult proposition. Two long lines must be isolated: the sheet and the control line which raises and lowers the sock. I attached the tack to the bow and led what I thought was an unencumbered sheet back to Sheryl in the cockpit. I went forward to connect the spinnaker halyard to the head of the sail and instructed Sheryl to raise it. It all looked good as a tube full of sail stretched from the bow to the top of the mast. I held the control line in my hand and started to gently pull.

The sock revealed the forward portion of the sail first and the crinkling sound got louder rather quickly. We were seeing 8-9 knots of apparent wind which, in retrospect, may be a little too much for flying our spinnaker. As the tack emerged from the sock, it became apparent that my control line was tangled slightly with the sheet. If I proceeded to reveal more sail, things would get ugly very quickly. With the snake now whipping its fan-like tail about 10 feet off the port side of the boat, I decided that maybe we should bring it down to untangle the lines.

I shouted back to Sheryl, in an effort to be heard over the boisterous sail, "Drop it!" My volume had suggested more urgency than intended and she very quickly lowered the silky fan-tailed snake. Portions plopped directly into the water before I could gather them on board.

With my heart beating loudly in my chest, I was thankful that I hadn't let too much of the sail out of the sock before noticing the problem. I also decided that one try was enough. With these winds, perhaps a different downwind technique was called for. I disconnected the head and tack, gathered up the lines, and stuffed it all back into its bag.

Next, we would try poling out the genoa (probably the technique we should have attempted first). Our whisker pole is mounted on the forward portion of the mast. It is connected to the mast at the top, where it runs along a track to lower it into place. The other end has a hook and pin which allow it to attach to the clew of the sail. When mounted on the mast, this pin also holds the pole in place. I discovered, much to my dismay, that it was held very firmly in place. Due largely to the fact that this pin has not been pulled in nearly two years, it was frozen.

Never fear, though, I have a solution. PB Blaster should take care of the problem; however, it often requires a little bit of soaking time. I suppose we can try it again tomorrow.

Strike two for building speed downwind was all I had the energy for. I felt an overwhelming level of defeat. I saw our hopes of winning the Race dwindling. Then Sheryl and a pod of dolphins came to my rescue.

For the rest of the afternoon, evening and nighttime hours, we were left with the option of sailing on as broad a reach as possible (until the genny luffed or we slowed down too much). In this manner we would slowly drift northward of our rhumb line, then gybe for a short southwest tack to correct back to the rhumb line. Note that we didn't want to stray too far north because the forecast suggested winds in coming days were to be from the southwest. Too much northing now would set us up for a potential head-to-wind scenario, right at the time we would be dashing for the finish line.

Unfortunately, I discovered in a short test run of the gybe-to-correct approach that there would be an 80 degree 'exclusion zone' where the wind would be too far aft to sail at required speeds. Amazing when you think of it. With light winds there is approximately 100 degrees of the head-to-wind arc which cannot be sailed. Add another 80 degrees of inefficient sailing speeds and you have half of the available sailing directions which are off limits. Sheryl will confirm the fact that I was wearing my frustration with the entire notion of travel by sail on my sleeve this afternoon. I give her all the credit in the world for continuing to support and encourage me when I was exuding pessimism from every pore.

The first contributors to my salvation came in the form of aquatic mammals. We have never seen them this far offshore, and (as always) their presence was a welcome sight. Dolphins are reputed to bring luck, and they have often appeared when we most needed them. In my case especially, this day was certainly no exception. I was at the helm when I spotted the first dorsal fin, and given my mood over the day's progress to our goal something occurred which was completely unexpected. A smile came to my face.

When my shift was complete, Sheryl took over for her late afternoon 1600-1900 hour shift. From my perch in the Nest below, I could feel that she was making good progress (you can hear the water rushing along the hull just inches away). I emerged to discover that during her 3-hr shift she rocketed along at an average speed of 6.9 knots! Sheryl often pushes the boat to go faster than I do; however, in our experience this is an unprecedented speed for such a long period of time. Especially with only 5-8 knots of apparent wind. Even though she had sacrificed a little more northing than I might have, she moved us 19 nautical miles closer to our goal. Spirits moved up another notch.

Thus, this became our rules for the night. Keep up the speed while sacrificing as little ground from the rhumb line as possible. An hour here and an hour there of southwesterly correction gybes brought us back to the magic line. The approach required us to hand steer, as SUE just couldn't keep us in the delicate alignment required with these levels of following light winds and still substantial waves. It made for a long night, but allowed us to complete Day 2 with enough distance made good to keep us in the running relative to the Race.

The unfortunate consequence was the path we took through the seas. The boat had a tendency to corkscrew off the waves. The motion can be described as a sort of unregulated roll with intermittent periods of rapid whiplash from port to starboard, but Sheryl said it best when she suggested that it felt as though Prudence was a wet dishrag and the sea was trying to wring her out.

We have grown accustomed to all sorts of motion at sea, and although we don't necessarily like it we somehow manage to tolerate it. These whiplash rolls were, to put it simply, beyond tolerance. Sleeping was impossible, because you were whipped awake every few minutes. Combine these frustrations with several shifts of hand steering and you arrive at morning's first light with two tired bodies on a boat in the middle of a big blue ocean.

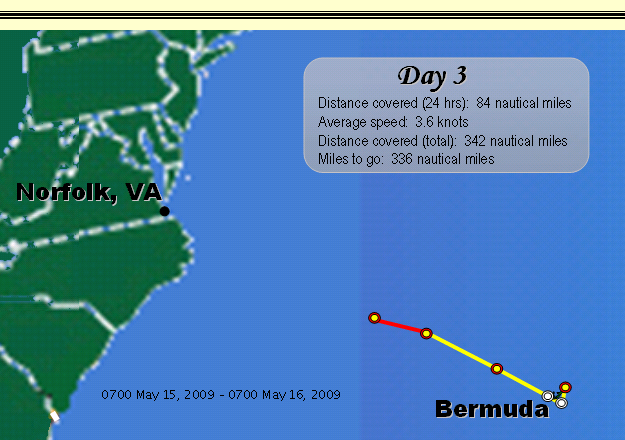

It was to be a day with a lot of sunshine, and the first thing we did when that beautiful golden orb appeared above the horizon was tilt the solar panels and turn the helm over to OTTO. It was also to be a day where we broke the limits of the 80 degree exclusion zone. Take two on downwind sailing techniques:

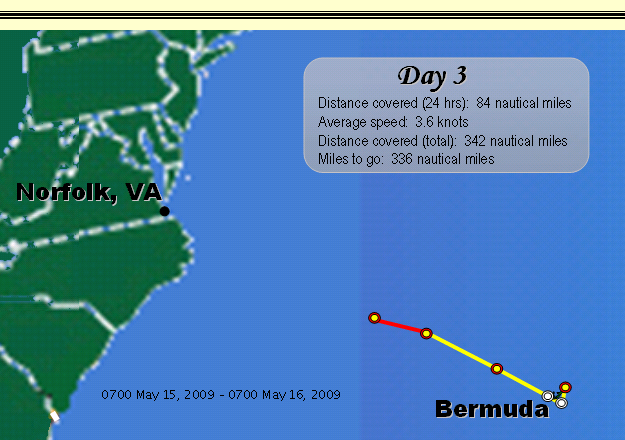

The first technique we used was a wing-on-wing approach. Today, the whisker pole pin worked free quite easily and we decided to run the staysail out with the pole and a preventer. With the corkscrew whiplash action still in effect, keeping the genny full of wind would have been next to impossible. On the opposite side of the boat was the main driver, a full main extended out as far as it would go with a sturdy preventer in place for safety sake.

This configuration kept us moving nicely directly along our rhumb line. Our speeds were a little short of our goal (appx 4.5 knots) but with 240 nautical miles to go before encountering the Gulf Stream, our hopes of winning the Race were still alive.

Unfortunately, winds continued to decline throughout the day. Our perseverance over the last 24 hours, and that visit from the dolphins, had bolstered my confidence and I was ready to, yet again, try the cruising spinnaker.

This time I took the snake out of the bag in the cockpit and organized all the lines before wrestling it up to the forward portion of the deck. And the patient approach paid off. This time the giant sail came to life just as it should.

The late afternoon and evening hours found us ghosting along proudly on 2-3 knots of apparent wind, making just over 3 knots of forward speed. Although this is nowhere near what we need to win the Race, it did move us along at a time where we otherwise would have been bobbing on the ocean's surface listening to the other sails slap back and forth in barely existent winds.

By sundown we needed to make a decision. If we had any hope of continuing in the Race, we needed to run the engine until the winds returned. With fuel supplies limited, we needed to carefully consider any use of the engine at this still early stage of the journey. In the end, November Mike (NOAA weather's automated voice) contributed greatly to the ultimate decision.

Mike indicated that the bad weather on Monday would now be starting as early as Sunday night. Phrases like 'North to northeast winds 25-35 knots' and 'seas up to 16 feet in the gulf stream' are fairly convincing. We admitted defeat and stood down in our efforts toward making it through the Gulf Stream before the bad weather hit. The Race had been lost.

Instead, we would wait until the weather passed to enter the Gulf Stream. Mike's long-term predictions suggest that conditions on Tuesday or Wednesday may be suitable. So, what to do until then? Well, the first and most obvious answer to us was that there would be no more worries about making the boat go as fast as possible.

In actuality, foregoing the Race turned out to be a great relief for a couple of tired cruisers. We would be spending a couple extra days at sea, but we should be able to make them more comfortable days. We started by putting away the spinnaker (before sunset) and putting the boat on a comfortable westerly broad reach. Yes, for those of you sailors playing along at home, the winds had started to shift from southeast to south.

We sailed through the night with SUE steering the boat through light winds with full main and staysail (no genoa). Both sails were sheeted down hard so that they were more quiet when we got tossed by the waves, and the result was an environment which was much more conducive to sleep. With 5 knots of wind or less we ghosted along at just a little over 2 knots of speed in a direction which was not exactly aligned with the holy rhumb line, but for once we didn't care. We have lots of time to kill between here and the Gulf Stream.

This morning the winds filled in slightly and came around a little to the west of south. We can now steer the rhumb line and are probably going a little too fast. No problem, we'll just put a reef in the main and slow our forward progress. I sort of like this approach to sailing: go slow.

With another exceptionally sunny day on hand (not a cloud in the sky), OTTO took the helm early in the morning, and we were free to read or write during our watches. With, of course, the regular 10-minute interruptions for the all-important horizon scans.

Generally when we are underway, I scribble cryptic notes in a notebook and sort them out later when I write the blog sitting safely in port. Today the conditions are such that I have plugged the computer in and am sitting in the cockpit. The sun is warming my face, powering my computer, and generating enough juice to give OTTO the energy to steer the boat. Life is good.

I am midway through writing about Day 2 when we are visited by another pod of dolphins. This one is smaller. Perhaps these fellows are just a few emissaries from the group to tell us that we made the right decision. I can imagine them saying, "Good idea to abandon that Race notion, mates. Stay here with us a while longer and enjoy this wide and wonderful ocean." Then, with a smile and a G'day, they were off (yes, in my mind dolphins speak with an Australian accent).

My morning shift is about to end and it is time for the midday broadcast from November Mike. Hopefully, I'll find time in the future to continue writing at sea. Getting the experience down in complete sentences as quickly as possible is sure to paint you a more colorful picture of life out here away from land.

Winds fill in overnight. We had forgotten what double-digit numbers looked like on the 'windicator'. We maintain a single reef in the main and fly the staysail with no genoa in order to keep our speeds down. Slow and steady may not win the race, but we hope it will get Prudence and crew home safely.

I awoke for my 0400-0700 shift and Sheryl suggested that we were experiencing a northward flowing current. Evidence to support this presumption was a deviation in our GPS trail while the magnetic compass indicated that we remained on course. We decided to watch it for one more shift and make a decision about what to do in daylight hours.

As I sat there in the morning's slowly dawning light, I had plenty of time to think about it. We were still 100 nautical miles from where I thought we would encounter the Gulf Stream. Yet, we kept drifting ever more northward without a corresponding change in compass heading. We were definitely sliding sideways. Perhaps it was a branch of the Stream or an eddy?

When Sheryl returned to the cockpit at 0700, we decided that we wanted no part of any northward flowing current considering the anticipated north winds to come. Therefore, we tacked back on a reciprocal course. Initially, we could not even manage that course because the flow continued to push us northward.

Sheryl got the bright idea of taking a water temperature reading. Our depth sounder is actually a triducer. In addition to depth, it also measures speed through the water and water temperature. Since we use GPS positioning to monitor our speed and depth soundings fade after about 35 fathoms, we generally leave the triducer off on long passages to conserve power. When we switched it on here the water temperature read just over 73 degrees F.

Several hours later, our northward drift had diminished and we saw water temperatures drop to just below 70 degrees F. Whatever it was, that current was slightly warmer than the surrounding waters, a tell-tale sign of Stream-like activity. Puzzling, though, so far offshore. Having escaped the clutches of current, at least for the time being, we tried to decide what to do here 250 nautical miles off the US coast.

Heaving-to is a popular way to stall for time on a sailboat. It essentially means pitting the sails and rudder against each other in such a manner that the boat no longer makes forward progress and instead slides slowly to leeward. Generally one backs the headsail against a trimmed main and turns the rudder to windward in order to stall the boat. We were worried about laying our genoa up against the staysail stay for a prolonged period of time (our limited offshore experience has taught us the destructive power of chafe). Therefore, we decided to try to heave to with a backed staysail and a reefed main.

The first attempt left us forereaching. This is when there is still some small forward momentum in the boat. It oscillates slightly up to windward, stalls, then falls back to a pathetic impression of sailing, and repeats over and over. Although this does achieve the desired effect of slowing the boat, the wave conditions were not good for keeping on this way. Heaving-to results in a slick of flat water to windward. This tends to break up waves and make for a comfortable ride. Forereaching still leaves a slick, albeit an anemic one, trailing more or less behind the boat. Without the protection from the wave action we were experiencing this day, the bow was occasionally taking a plunge below the tips of the waves (something which it never does when we are underway).

We tried to convert the forereaching into a proper heave-to. We added a little genoa (but not so much to make contact with the staysail stay), we reduced the main by putting in a second reef, but all were to no avail. We simply couldn't get balanced in a way which would make us comfortable for the next 48-hours while the bad weather passed through.

So, we rolled up the genoa, left that second reef in the main and started sailing slowly. One of our favorite stall techniques is simply sailing slowly and pacing, if necessary. We were at liberty to choose a point of sail which was most comfortable in the ever-growing winds and seas, so we struck out first in a southeasterly direction on a close reach, then changed to a broad reach which carried us to the northeast.

Like a prowling panther, Prudence bore us patiently along, ready to pounce on the Gulf Stream when the timing was right. I wish I could say that the humans aboard were demonstrating such poise. We were getting tired and very ready to go home.

It is Monday and it is far enough out that the bad weather carried by an approaching cold front has yet to reach us. We started the traditional work-week still in stalling mode. The broad reach from last night had been a comfortable point of sail; however, it had carried us close to 300 nautical miles offshore and we simply did not want to go any further a field. Therefore, we gybed the stern through the wind and adjusted our double-reefed main and staysail to carry us slowly toward our next waypoint.

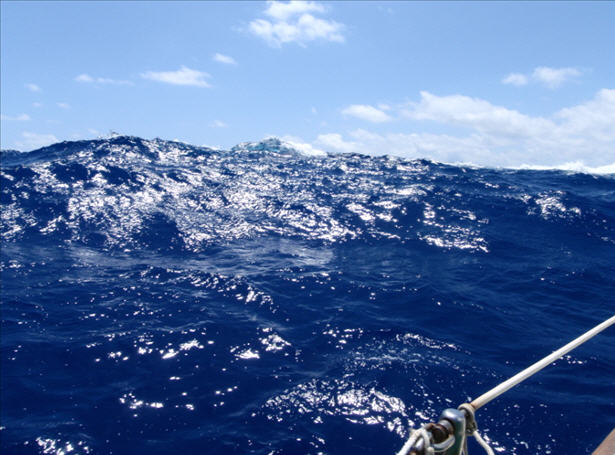

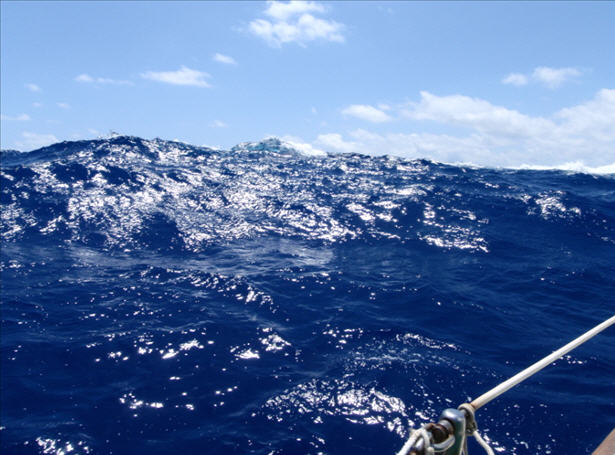

Sailing on a close reach through gigantic seas we are lost amidst walls of water when we slide down into the valleys. At an average speed of 3 knots, Prudence climbs slowly over a blue mountain range tipped with frothy white foam. She picks her way over one wave at a time turning a terrifying visual display into a gently gliding series of ups and downs. I suppose that this is what they mean when they use the words "sea-kindly" to describe a vessel.

I am back at the computer today. Writing in real-time allows for much more descriptive prose. We are currently getting enough sun between the scattered clouds to not only power OTTO, but to generate a surplus of electricity for my computer. In fact, this is our longest journey ever without starting the engine. Boat traffic on this trip has been such that we have not needed the assurance of diesel-driven maneuverability to avoid close proximity to big ships. It is good to know that we are solar sufficient while underway, as the pattern of power consumption is different on passage. Having experienced numerous occasions of living for over a month at anchor without an engine start, we knew that we were just fine under those conditions. We can proudly state that, to date, we have never had to start our engine simply to spin the alternator.

Other than the diversions offered by reading, sleeping, or the occasional opportunity for time at the keyboard, our lives are ruled by the clock. The 24-hour day is divided into 3-hour shifts, and each shift is divided into ten-minute increments. Rather than become frustrated with our lack of progress in terms of distance to our goal or get bored with the monotony of it all, we try to focus only so far as getting to the end of our shift, or sometimes just making it to the next 'ding' of the ten-minute cycle.

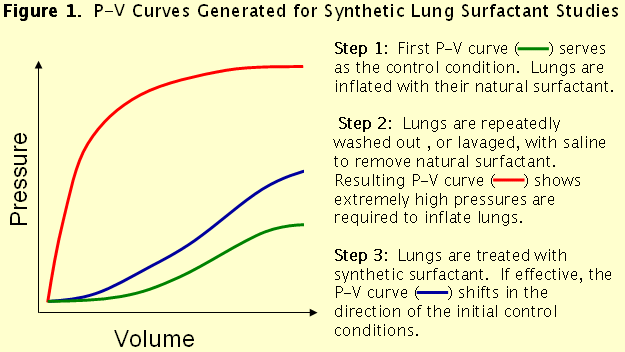

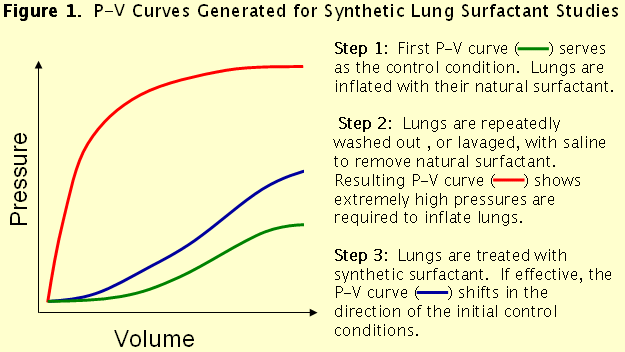

I recall a time from my young adulthood where I was similarly ruled by a proverbial stopwatch. I was in college and had secured a position working in a cooperative program with a local pharmaceutical company. It was a respiratory pharmacology lab interested in developing a cure for Respiratory Distress Syndrome (RDS). Although RDS can also occur in adults, the main victims are babies delivered prematurely. A substance in the lungs known as surfactant is not produced until the later phases of gestation. This substance is crucial for breathing. Essentially, it lines the small air sacs in the lungs and breaks the surface tension such that they can more easily fill with air. In the absence of surfactant, infants must be placed on a respirator (something which itself can be damaging to such fragile young lungs).

The lab utilized animal models for testing artificial surfactants, so before I go on, let me first indicate that I will not be responding to any e-mail which challenges the use of animals in research. I have had enough discussions with PETA-type people to last a lifetime. Save to say that the rats I worked with were born and raised for the sole purpose of research, were treated to clean and comfortable housing conditions, handled with care and respect, dispatched in the most humane manner possible, and sacrificed only when necessary to answer important questions in an effort to eventually save human lives.

My mornings at the lab would start with a cup of coffee and surgery. One cup was all I could afford because I needed steady hands to remove a pair of lungs from a rat, intact. The tiniest cut or puncture of the very delicate lung tissue and I would have to start over. Leaky lungs would not work for this experiment. Once the lungs and trachea were isolated, a tube was connected which ran to a carefully calibrated syringe pump and a manometer (capable of accurately measuring tiny changes in pressure).

The lungs were placed in a bath of isolated saline, warmed to body temperature, to simulate the in vivo environment. Then P-V curves were generated by measuring pressure changes while lungs were inflated at a constant rate by a known volume of air delivered through the syringe pump. (see Figure 1)

In addition to the carefully timed pressure measurements while the lungs were inflated, between each inflation the lungs had to be placed in a vacuum jar to remove all air from the lungs (simulating an infant's initial breathing situation). We called this 'degassing' the tissue. Although only three curves are shown in the figure above, many repeats of the inflate, degas, lavage, inflate cycle were required to ensure that all of the surfactant had been removed and that the lungs were ready to test the synthetic substance. So, the better part of an entire workday was ruled by the 'ding' of a timer, much like my current circumstances.

In any case, I took this seemingly tangential break from the main story line to illustrate a point. We are left with a lot of time to think while floating along on our tiny 35-foot island surrounded by an infinite landscape of blue. Often memories surface that allow you take stock of your life. In the larger perspective, what we are is the sum of the experiences which quickly become memories. Soon this moment, this passage, even the overall interlude into the cruising lifestyle will be but a collection of memories. I suppose I should cherish the experience whilst I am within it. Wait, I just heard a 'ding', it's time to scan the horizon for the seven millionth time.

Today I drank my last ginger beer. I have tried a wide variety of local ginger-flavored sodas available in specific parts of the United States and down island, and in my opinion Barritts Bermuda Stone Ginger Beer is one of the best I have encountered. The flavor is quite excellent, I must say. In addition, it was available in diet, something you don't often get to select. I have discovered that the ginger and spice flavor is enhanced by enjoying the beverage at room temperature. (Perhaps we won't even bother turning on the refrigerator when the boat is once again plugged into shore power.) I purchased a six-pack before we departed Bermuda. It is a not-so-subtle reminder that 6 days have passed and we are still a long way from our destination.

Although the day had been reasonably enjoyable, our night would be a different story. We had been waiting all day for the winds to shift to the north, indicating the arrival of the expected cold front. This is the bad weather which arrived over the Gulf Stream last night and has been the source of our delays.

The front finally reached us in the form of a long line of dark clouds. The line stretched from horizon to horizon and was dotted with grey shower activity. Interestingly, as we approached it (or, rather it approached us), there was an open space between two large showers. The clouds above were continuous, forming a giant arch of ominous black cloud supported by grey columns of rain.

As we passed directly though the center of the arch I looked left, right, and above. It was a surreal experience, almost like sailing through a big doorway. Very shortly we would learn that we had just crossed the threshold into hell.

Beneath the arch, the seas became confused. It was like putting a dog dish on one of those old electric vibrating football games (not that I have ever done that). In addition to the crazy dancing waters, the winds all but died. Sheryl came up on deck just as I was rolling out the genoa. The additional sail got us moving again, but was only required for a few minutes. Soon 5 knots became 10, 10 became 20, and 20 became 30. As the sun set, we started what was to be a 15-hour journey through the aquatic equivalent of an inferno.

One of the trends which we have been observing with each passing night is the later and later arrival of the moon. Arriving on the scene almost 1 hour later each night, this ever-shrinking companion which gave us a view of the seas at the start of our trip now barely beat the return of the sun. Therefore, on this night we would be without any lunar illumination of the water's surface. Not that it would have mattered much. We were under a solid ceiling of clouds. No starlight, no satellites, no airplane lights, nothing.

Sailing through absolute blackness was scary enough, but the second sense to be assaulted was our hearing. The sound of wind shrieking through the rigging (consistently at 30 knots, gusting higher) is something you never quite get used to.

Then there were the roller coaster waves. November Mike had been predicting up to 13-foot waves, and it certainly felt like my stomach was being repeatedly dropped at least that far. The waves also contributed to the sound track. Our boat is very sea kindly and moves over the water in a miraculously graceful manner. Unfortunately, some waves seem to be made of concrete. Every few minutes there was a concussive blast that sounded like you were standing at a corner when a head-on auto collision occurred right next to you. These were often followed by a 10-gallon bucket of seawater being tossed into the cockpit.

Rain was intermittent throughout the night. Of course we couldn't see it, but we were obviously moving between numerous shower cells trailing behind the leading edge of the front. Top all of this off with an ever-present mist of saltwater spray in the air and those buckets of seawater flying around the cockpit and you the recipe for a very soggy way to spend your on-watch hours.

Considering all of those heart-racing and morale-diminishing stimuli, none affected us as bad as the worry over encountering other boats. We were both fairly certain that with the current visibility any notice of the proximity of another vessel would be very short notice indeed. Charging along thru the blackness on this close-hauled starboard tack, we asked ourselves, "What should happen if we suddenly see the red navigation light of a ship appear, through the thick dark veil of raindrops, immediately off our starboard bow?" Tacking through these winds and seas with our minimal sail may or may not succeed, gybing would be quite a roller-coaster ride. The engine might help, but with time required to open our exhaust output seacock (an addition we made to make certain that following big seas cannot flood our engine when we are under sail) and warm the glowplugs it would be a minute or two of absolute chaos, at least, before we could have the engine on. The ghost of this notion haunted us as the night wore on.

In order to deal with the specter of potential boat traffic, we kept trying to continuously scan the horizon through the dodger and peek our heads out without wearing a bucket of seawater. We moved about the cockpit from side to side with much effort. When on the high side, we had to hold on for dear life to keep from being thrown across to the leeward side of the boat. And, yes, Moms, don't worry, we were attached to the boat via our safety harnesses before we even set foot out of the companionway. Rule #1 aboard Prudence: STAY ON THE BOAT.

In summary, it was absolutely terrifying. The cumulative conditions were worse than anything we have ever experienced under sail. Even the worst squalls were not this bad, and they ended after a few moments. This one felt as though it would never end. In fact, that was one of the toughest parts. Not knowing how long we were going to have to suffer like this was a torture in itself. If only I had a program for this event, I could prepare myself to hold on just a little longer and it will end. In addition to a program, there were points where I really could have used an intermission, as well. Unfortunately, heavy weather is not a play.

As with our approach to other aspects of this undertaking (i.e. the boredom of long passages), we coped with the situation by tackling 10 minute increments couched within 3-hour blocks of time. We tucked up under the dodger and tried, in vain, to stay dry. Meanwhile, SUE did an incredible job of steering the boat. We have learned on these last two passages that no winds are too strong for her. She holds a course, relative to the wind, through it all. In addition, SUE never complains when she is the direct target for a bucket of seawater.

We set SUE to hold us as close to the wind as possible. At this point of sail, the sails are held slightly de-powered and the gusts cause a subtle luffing which tends to diminish their power. Still, with only the staysail and a double-reefed main, we were consistently doing over 4.5 knots. We debated about dropping the stay and turning to run (another way to make things more comfortable). However, nobody on Prudence goes forward of the dodger in conditions like this unless ABSOLUTELY necessary. In addition, these waves could be quite dangerous if we put them on our stern. So, we headed northwest, into the direction from which the front approached, hoping that we could move through it faster and bring this madness to an end.

In this crazy and frightening experience, we supported each other most by giving the other the ability to at least try to disconnect when not on watch. I have absolute trust in Sheryl's ability to monitor the helm in this situation and keep herself safe as I went below to the Nest and surrounded my body with blankets and pillows. One could not dissociate from the circumstances entirely, though. From below it sounded as though the boat were being torn apart (though we both know it was built to take much more than we are capable of dealing with).

One minor consolation to the entire experience was that we had made the right decision in abandoning the Race and spending time at sea stalling. If we had encountered this in the middle of the Gulf Stream, it could have been a lethal mistake.

I had the sunrise shift, and I was never so happy to see that golden orb. Well, I should say that I was happy to have a little grey light, for we did not see the sun at any point on this day.

The slowly growing grey-like illumination revealed a world of water chaos around us. The waves were absolutely HUGE. I thought we had seen big waves yesterday before crossing the threshold of the front, but these were unlike anything I had imagined. Through the nighttime hours, deprived of our sight, Sheryl had suggested the intensity of the sea state when she said, "I can tell the waves are huge because the sound through the rigging changes when we are down in the troughs compared to when we are perched on the peaks."

Now that I could see them I understood why. When we rose to the top of a wave and sat on the edge ready to slide down, I could look down into the valley. It was like standing on the balcony of a second story house. When we were down in the valley of the waves you could nothing but a grey wall of water, streaked with white tendrils of foam.

Overall, though, I was most amazed that we could even survive in this. A sailboat is a remarkable thing, and the way it moves along through seas like this is an experience I will not soon forget. I found that I was having trouble focusing on the horizon during my regular checks. Instead, I would feel the motion of the boat beneath me and become mesmerized by the spectacle of the nearby waves.

Fifteen very long hours after it started the constant assault of 28-32 knot winds finally started to abate. Even when the winds dropped to 24-27 knots (strengths we usually find intimidating), it was an improvement beyond compare. While the seas remained high for a time, the slight decrease in winds afforded a decrease in our forward speed. Just a half knot less and the 'concrete' waves appeared much fewer and further between.

By mid-afternoon, the seas were down to a size where we feel comfortable trying to change our point of sail from close hauled to a broad reach. What a difference this makes. We decided to push the wind even further aft and drop the staysail so that we were running under a double-reefed main alone. Despite this limited canvas, we were averaging over 4.5 knots.

So we entered the dark moonless hours, once again, with just this tiny bit of sail pushing us through the night. At one point just at the start of Sheryl's shift, a light was spotted on the horizon. It had an odd orange cast to it, but that was not the alarming thing. What was alarming was the rate at which the vessel advanced. It was on us in no time, bearing right down upon our location. We scrambled about opening our exhaust output seacock and warming the engine with glowplugs. Once the engine was running, we switched on the radar and noted that the boat was within our 2-3 nautical mile comfort zone and we tacked to put some distance between us and what we believed to be the path down which the big boat was heading. These events are always more frightening at night, when you have no idea exactly what is approaching you, you somehow just sense the enormity of it. Once it was safely past, we relaxed and reflected upon the fact that at least it was good that this had happened on this night (of good visibility) and not the previous one. Although I hate to imagine the consequences of that ugly specter again, if such an encounter had occurred exactly 24-hours earlier ... well, let's just say I may not be here writing this blog today.

After the excitement, we shut down the engine and refocused our concentration on our plan for the night. Our goal was to make it to a good position for entering the Gulf Stream in the morning. Wednesday, one week after our departure from Bermuda, would finally find us crossing the Stream. November Mike was calling for big winds to continue from the north on Wednesday, followed by a shift to east and moderation on Thursday. If we had been further away, we would have waited another day to cross; however, since we were sitting ring-side and our own onsite weather monitoring saw decreased winds and seas all around us, we decided to go for it at first light.

Sheryl was at the helm on this particular sunrise shift. As the nighttime winds had continued to fall, I had deployed a partial genny to keep the boat moving along. Sheryl had unfurled the remainder of the big sail and was even thinking about starting the engine because the winds had dropped so much. This was certainly not the northeast winds at 20-25 knots that November Mike had predicted for the area.

To be fair, this may have been a localized effect because before Sheryl had a chance to start the engine, the winds filled in. I awoke to find that I had been given an extra hour of sleep (thank you, my Love) and that we were moving along at a good pace, powered solely by the wind, through some pretty decent sized waves.

As soon as you enter the Gulf Stream, wind and waves begin to be amplified. I took the watch and we decided to leave the two reefs in the main and fly the full genoa. This combination gave us good speed since the main did not blanket the genny, while still allowing the mainsail to provide stability against rolly motion in the ever-increasing following seas.

Winds went up into the 20's again, but would occasionally drop down into the teens. We managed to keep the boat under control by switching between a very broad reach and running. While on a reach the apparent winds would soar, but when running the numbers would drop. We simply had to be careful not to let the wind get around and back the genoa.

Keeping absolute control over our course was a necessity due to the following seas. Large enough to produce a field of white horses, these breaking waves were fast approaching double-digit height. OTTO has the most fine control over a directional course, so I let him steer while I stood in the Cage (our name for the helm station in our cockpit, due to all the stainless steel bars which make up the stern pulpit, bimini and solar panel supports).

I made continuous minor adjustments to our course to keep us aligned with the wind such that our forward speed was always less than the waves. This kept us from surfing down the face of a big following wave, which may result in nose-diving into the next wave. This is the time when a double-ender sailboat really shines. The water divides nicely and flows smoothly past each side of the pointy end of our canoe stern. Several crested beneath us, and you could taste the salty foam in the air.

On smaller waves we can carefully get a lift by surfing the sides of them. Forward speeds can briefly peak over 10 knots, and it is certainly exhilarating, shooting along the face of a wave with a 20,000-lb surfboard. However, we needed to be careful not to try this on too large a wave. I don't know what it would take to knock us down but I'm not anxious to find out.

Near the middle of the Gulf Stream, I decided that it was time to attend to a long overdue event. It was time to say goodbye to my beloved hat. I have had this hat for so long that I cannot remember exactly how many years it has been. Better than a decade to be sure. It was initially purchased as a 'beach hat' at a time when going to a beach was a rarity (I lived in land-locked central Indiana). It traveled broadly with me throughout the years, and eventually became a symbol of weekends and vacations. I wore the hat on my time.

When I first met Sheryl, and she taught me to rollerblade, it was always perched upon my head as I labored on wheels, trying to keep up with lightning-fast Sheryl (we often passed bicycles on the trail, a sure sign of speedy blading). Sheryl marveled at how the hat never blew off my head no matter how fast we moved or how hard the wind gusted. I told her that the hat had undergone years of training on my head to accomplish that degree of tenacity.

When we transitioned our leisure time to sailing, the hat was a natural. Its perfect fit meant that I did not have to worry about practicing our man overboard drills to retrieve it from our wake. Despite the fact that it started showing significant signs of wear before our departure to go cruising, I held fast to the belief that it might last forever. The summer before departing North Carolina, Sheryl applied a couple of iron-on patches to the inside to shore up some weak spots.

Over the past two years the hat has been aboard my skull for all passages. It turned out to be the perfect protection for my balding head when we ventured out in our kayaks. I even became known in Culebra as that guy with the hat. People would tell Sheryl, "Oh yeah, I've seen your husband walking along the road in that hat."

But the constant exposure to the tropical sun and salt water beat down upon the hat and brought it toward a further state of disrepair. More iron-on patches and needle & thread were brought to bear upon the wounds. We managed to shore it up well enough to make it through one more season of sailing. It wasn't pretty, but it remained well-trained and functional.

Over the past few months, the structural integrity of the hat has begun to fade. Its former perfect fit began to loosen and I could no longer take it for granted that it would remain on my head in gale-force winds. I knew the end was at hand.

So, this morning, at this place and time, it struck me. What better way to celebrate this remarkable journey than to sacrifice my hat to King Neptune? It was time for a burial at sea.

There were no words said, as mere words could not do the relationship between me and my hat justice. I simply took a moment to recall all of the good times, and there have been many, many good times. Then I tossed it into the Gulf Stream. As it rapidly flowed away, a weight of sadness descended upon my chest. Although I have been training its replacement, a gift from a friend (thanks Nydia), for almost a year now, I doubt it will ever be the same. Goodbye, old friend.

Just as the Gulf Stream was reaching its crescendo with large confused seas and a rapidly flowing current to the northeast, our lunchtime entertainment began.

I was listening to the midday broadcast of November Mike when Sheryl shouted, "Dolphins, and it is a HUGE pod!" Mike was coming in pretty poorly anyway, so I decided to wait and listen to the afternoon broadcast and instead go say hi to our good luck charms. Despite the sloppy seas, Sheryl went forward with her camera.

As soon as the dolphins departed it was time for lunch. Sheryl went below to prepare our repast when I shouted, "Ship sighted. Big ship." Sheryl came up to provide her opinion, and we both agreed that it was getting bigger rapidly. Sheryl went below to turn on the radar when the VHF radio sounded. It was a coast guard ship announcing that they were testing live ammunition and warning vessels to stay away from their location. They gave coordinates, but we didn't catch them.

Sheryl decided to call them back to get the coordinates, just to make certain that the big ship approaching on our port was not playing with live rounds. The coast guard cutter Bear responded with coordinates which were over 30 nautical miles from our position.

So, we turned our attention to the big boat drawing closer on the radar. Soon we could see what looked like little bees buzzing above this huge ship. We surmised that it must be an aircraft carrier. When they drew to within 3 nautical miles, Sheryl hailed them.

Finally, it was time for lunch.

The Gulf Stream ended much more suddenly than it began. The approach involved slowly increasing sea temperatures (from 69 up to a peak of 77 degrees F), slowly increasing current, and ever-worsening sea conditions. Once we passed the peak things rapidly improved. The seas laid down and immediately we saw a water temperature of 58 degrees F.

Before the Stream, the water was of the deepest blue color. Here after the Stream, it is a dark green. Before long the water in our onboard tanks was coming out cooler than it has in a year and a half. Refreshing for drinking, but a bit of a shock when you go to wash your hands. As evening approached, we turned the cowl vent backwards in an effort to stem the cold air flow into the boat.

The evening entertainment was also provided by the military and marine mammals. This time we really did see an aircraft carrier, complete with jets taking off and landing from its surface. We did not have to hail this one, as its orientation, heading and speed made us fairly certain that it would pass to our stern. It did, about 3 nautical miles away, while several jets roared around it with their thundering engines.

Immediately following was another visit from the dolphins. We continue to receive healthy doses of luck during each stage of this voyage. This amounts to more dolphin sightings than we have ever before experienced on a single passage. Note the change in the color of the water now that we have passed the Stream.

The post-Stream winds were light and slightly aft of the beam. The seas had calmed and there was minimal swell. It is what I imagine sailing on a lake must be like. We threw up all of the sails in hopes of making maximal progress toward our destination. Sailing in light air is like trying to tune in a distant AM station on a cheap radio with an analog dial. In a word, frustrating.

Once I got the sails adjusted, I tried to engage SUE, but she was not happy. She could not seem to steer a consistent course. She struggled against weather helm and then fell off too far. I played with the sails for a while longer before discovering that I really needed to drop the staysail when winds are aft of the beam even slightly, because they were so light. Surprisingly, heavier winds are more forgiving. Now SUE was happy, and she had taught me a little about appropriate sail configuration and trim in the process. It seems that this sailing is an activity one continues to improve upon, but never quite perfects.

Although the lunchtime and evening entertainment were good, the best show was reserved for the nighttime hours and I was the sole audience. The night was dark but very clear, as a high pressure system had settled in place in the wake of the cold front and drove off all of the clouds. The sliver of remaining moon would not be up until 3AM and it was just now turning midnight. A soft glow of a city warmed a spot on the horizon just off our bow (probably Virginia Beach), but is still far enough away not to pollute the spectacle of a billion stars in the sky. As we ghosted along on the light post-Stream winds, the waters were flat calm and I could see little spots of bioluminescence beneath the surface. They would blink on and off like fireflies set into glass.

Suddenly, there was a sound right next to me from the water beside the cockpit. "Phhhhssh." And, during the next hour I enjoyed my first nighttime visit from the dolphins. Although I could only barely see their fins surface in the starlight, I could definitely hear them breathing through their blowholes. Occasionally, when they moved quickly through the water a comet's trail of bioluminescence would briefly follow.

In what was to be their grand finale, several of the dolphins got hyper and raced along the side of the boat trailing crossing streams of soft glow in their path. I was tempted to run down and wake Sheryl, but figured that they would depart just as she came up the companionway. Sure enough, as soon as I completed the thought they were gone. I would tell her about them when I woke her in an hour or so.

In the wee hours of the early morning I woke Sheryl to start her shift. In addition to relating the nighttime dolphin show, we discussed our arrival time. Based on our progress in these light winds it looked as though we would be making a nighttime arrival near land. In order to move that up to daylight hours, we needed to start the engine. Neither of us could see spending another night at sea.

Once the engine was purring and Sheryl was set for her watch, I closed the book on my shift. I am hopeful that this marks the final night watch I ever have to make it through, as we have no plans for further passages involving overnight sailing.

I woke from my 3-hour sleep to find in the backdrop behind Sheryl hung a sliver of moon sitting just above the prismatic color bands of the predawn horizon. During my shift, the sun rose and the moon faded into the background of an ever-brightening blue sky.

The views at sunrise and sunset during these offshore voyages have been amazing. Sheryl has captured some wonderful shots which show the incredible colors and textures brought about by our closest star.

[Be certain to check out all of the full sized pics, uploaded to Sheryl's Flickr site ... see links at upper left corner of this website]

The cockpit is damp with a heavy layer of dew, aided, I am sure, by the water-drawing effects of a fine layer of salt which coats everything. Despite this, I am happy. The engine is humming along, and with the surplus of power the radar is spinning and OTTO has the job of steering us to our next waypoint. I can sit and enjoy my morning coffee and keep an eye out for boats.

There are a lot of boats as we approach the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, but we navigate among them with no issues. Sheryl and I are both excited and these final hours are dragging by slowly. Sheryl uses the time and alternator-supplied electricity to sort through photos during her off shift and I write a few more days worth of blog.

By noon, we spot land. It is such a glorious sight. We have made it. Or, at least we thought we had. Soon we note a line of ripples in the water and beyond it a change to slightly browner water. We both know what that means, from previous experience with ocean inlets ... tidal current. Even though low tide at the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel was at 11:50, we are still seeing a very strong current here just over 10 nautical miles out. Our forward progress has slowed from nearly six knots to about 3. It becomes a long, slow slog to the bridge.

Once we are close enough, we hail a marina which is located just around the corner from the cut through the bridge (thank you so much for the recommendation Brent). We are happy to learn that they have space. Of course, now that we are nearly there, the winds start to fill in. We raise the main and motorsail the remaining distance to the marina.

CLICK HERE in order to continue to Part 2 ...

The Race is about to begin. The competitive nature of the journey between the east coast of the United States and Bermuda under sail has a rich history, or so I have heard. Not being an aficionado of sailboat racing (or any sort of racing, for that matter), I draw that conclusion from what I have stumbled across in my reading of sailing magazines over these past few years.

I would pick up a copy of SAIL magazine and rapidly skip past any of the articles describing tips and tricks to help you win your next local event on the water, in favor of an article describing the dire circumstances of some casual sailors. One article I recall described a fellow out for a day sail who tucked down below to discover the floorboard hatches to the bilge were floating (a loosened stuffing box turned out to be the cause), or another where a couple on a boat just off a dock suddenly lost steerage because a long handled scrubby brush had become entangled in the cable to the steering quadrant. These articles always ended with a 'Lessons Learned' section which I found most enlightening. Better I learn from their mistakes than make them myself. On the counter end of the educational motivation spectrum, though, I had little time and energy for cataloging the details for wringing that extra half-knot of speed out of my boat. Too bad, for it may have been of some use to me on this particular trip.

This Race, of our own design, is a direct product of our selection of weather windows. We will not be facing any other boats in this challenge, instead we will be up against Mother Nature herself. Our long-term weather outlook shows a fairly strong cold front will pass off the coast just as we are arriving at the Gulf Stream. With this type of passing weather system, winds generally go from southwesterly to northerly in very rapid succession, and this one was predicted to be no exception to that rule. Our task is to get the boat past the Gulf Stream before the winds switch to a northerly direction. The Stream flows north, and the circumstance of wind against current is to be avoided at all costs. It causes large square-shaped waves. Not good for folks on a small boat.

The timing is such that we need to maintain a 5-knot overall average to cross the Stream before doomsday on Monday. This is certainly doable, but will require steady winds from the right direction. And, based on our analysis, winds should stay better than 10 knots (more often in the realm of 15-20) ranging anywhere from northeast to southwest, which is perfect for our northwesterly course.

So, with anxiety mounting, we make the commitment to depart by checking out with Customs and Immigration on Tuesday afternoon. Aboard Patience, Sheryl battled some big, pointy waves in the harbor which have been stirred up by two days of strong southwesterly winds. She presented herself with papers for departure in hand and, perhaps prompted by her somewhat sodden appearance, the officials asked, "Have you checked the weather forecast?" There is nothing quite as effective as that particular question to squash your confidence and make you doubt your decision. To her credit, Sheryl didn't tell me about that exchange until several days into our journey. No need to add to my already monumental anxiety. She simply responded to their inquiry in the affirmative and went on about the business of making our departure from Bermuda official.

The forecast had called for a decrease in wind strength and a shift to the north this evening. These are the conditions under which we wished to depart. Unfortunately, there was no sign of those conditions when Sheryl returned from her final Bermudian errands. I balanced aboard the dinghy on sharp waves as I lifted the outboard engine up to Sheryl who was standing ready at the stern rail mount. Just as we were hauling the dinghy from the water, the chop in the harbor began to subside. By the time I had the dinghy stowed and the cockpit locker completely repacked (a process which takes about an hour), the water surrounding the boat had become a mill pond.

As darkness descended upon us, a gentle wind pushed us around our anchor until the bow was pointing north. We both breathed a heavy sigh of relief. We briefly considered a nighttime departure, which would give us a 9-hour edge in the Race, but a quick look at the chart and all the shallow reefs surrounding the islands of Bermuda was all it took to put that idea to rest. Speaking of rest, we savored the final evening of togetherness and uninterrupted sleep. At least as much as our nervousness regarding the nautical miles before us would allow.

First light on Wednesday morning brought with it the welcome sound of several other anchor chains being returned to their respective lockers. We did not know where these other boats were bound for, but we took solace in the fact that others obviously concurred with our opinion that this was a good day to be under way. The mere sight of others getting the jump on us, so to speak, spurred us to action even more quickly than our own eagerness to begin the Race otherwise would have.

We quickly rearranged the boat into our version of 'offshore-mode', and started the engine. While I removed the snubber from the anchor rode, Sheryl called Bermuda Harbour Radio on the VHF and requested permission to navigate the Town Cut. A light drizzle began to fall. We received the O.K. to exit the harbor and I labored to lift our chain and anchor aboard. I was drenched with sweat within my foul weather gear and with rain on the exterior as I returned to the cockpit. Sheryl later indicated that the sight of me brought to mind the proverbial drowned rodent.

By approximately 7AM, we were out through the Town Cut and rounding the SPIT buoy. Therefore, we decided to measure each of our days on this trip with the start/end time of Oh-700. This day was turning out to be a fine day for sailing, but less than agreeable from other weather perspectives. It was drizzling and somewhat foggy (although visibility was such that we could still clearly spot a cruise ship over 2-nautical miles ahead, thank goodness). Eventually, the rain ceased, but the cockpit and its inhabitants remained damp under a sky which was a solid blanket of grey clouds.

The engine was silenced within an hour of its start time, and we struggled to find the correct sail arrangement for the conditions. As we navigated a semi-circle around the southwest corner of Bermuda, we surmised that land effects were the likely culprits causing these variable winds. Just a few more hours and we wouldn't have to worry about those pesky land effects again for several days.

Early afternoon found us on a rhumb line which extended over 600 nautical miles to Norfolk. But our focus was on a region of the Atlantic that was slightly over 100 nautical miles closer, the Gulf Stream, our finish line for the Race. Once we were on the rhumb line, we made good progress toward our destination. Despite this fact, my anxiety was at an all time high. I had to make a very conscious effort not to clench my teeth, a nervous habit of mine. My dentist has suggested that the pressure is causing tiny stress fractures to form in my precious pearly whites (and that was before we left to go cruising). Try as I might, I still occasionally discover my chompers mashed together without my even knowing it. Due to this dreadful habit, my teeth actually ached for three days after our arrival in Bermuda.

Late in the day I started noticing the first signs of seasickness. Unfamiliar to me until just a few weeks ago (at the start of our previous passage), the nausea, headache and general malaise settled in even before nightfall. I suppose that my body has learned this response to the motion of the ocean supplied in combination with the elevated adrenaline which accompanies a perpetual state of anxiety. I took some of Sheryl's medication to help me cope (seasickness meds not anti-anxiety drugs, although some valium would have been warranted).

Strangely enough, reading, for me, helps to relieve the symptoms of seasickness. For Sheryl, it is an activity which can only be pursued once such symptoms have subsided. Perhaps it is the escapist nature of losing myself in a book which transports me away from the stresses (both physical and mental) of my surroundings that allows this modicum of relief. Regardless, I am grateful.

I spent my downtime in the cozy sleeping settee in the salon, which we have dubbed the Nest, enjoying a book by Bill Bryson (one of my favorite authors). Sheryl spied this gem in a book exchange at the visitor's information center in St. George's Town. For a time, I am not on a boat in the Atlantic, I am in England with Bill. When on watch, I continue to read but with frequent interruptions which tend to make the escape more difficult. I let SUE steer the boat while I am reminded by my new kitchen timer to check the horizon for boat traffic approximately every 10 minutes.

The onset of darkness brings an end to my reading while on watch, but the kitchen timer continues to aid the regularity of my horizon scans. When I purchased this item in Bermuda, I elected to go with the old fashioned spring mechanism over an electronic timer, largely for the sake of it holding up to a potential dousing with salt water (it only has to last this one trip, then I will be through with long passages forever). The downside to this non-electric gizmo is the lack of any lighting. I cannot see where the 10-minute mark is when I twist it in the dark.

Initially, used the red LED flashlight we keep in the cockpit to illuminate the dial, but quickly learned to simply listen to the subtle clicks made by the clockwork mechanism as I twisted. Six clicks was equal to 10 minutes. So, I spent the first of many dark 3-hour shifts to come as follows: click ... click ... click ... click ... click ... click ... wait ... ding ... standup ... turn a 360-degree pirouette while looking at the horizon for any signs of light... turn back the other way in order to unwrap your safety harness tether (double checking for any lights) ... sit back down ... and repeat.

It was obvious from the start that this day would be much sunnier than the last. Despite the good general weather conditions, we were having trouble adapting to the sailing conditions. The winds had shifted around to our stern and were forcing us to run in order to maintain course and speed along our rhumb line. Although we had the good fortune while in the tropics to experience an occasional broad reach, by and large the wind was always forward of the beam. This was the first time for us to attempt to run before the wind in a long, long time.

When the wind is behind you, the sailing experience is entirely different. The wind you are creating by moving forward is subtracted from the actual wind, meaning that much greater speeds are realized with lower apparent wind. Although you may be going 5 to 6 knots, you do not feel the wind on your face as you do when sailing close hauled or on a reach. Initially, we tried to go wing-on-wing. This had worked wonders for us back in the Neuse River. Unfortunately, ocean swell and running wing-on-wing in light air are mutually exclusive. No matter how I tried, waves would kick us around and cause one or the other sail to flog or back.

With winds becoming lighter, we discussed the option of digging our cruising spinnaker out of the cockpit locker, and were eventually driven to it by the incessant flapping of the genoa as we fell off of waves. I don't know whether it was the residual seasickness or the fact that I simply had not yet found my sea legs, but as I took the bag containing this big sail forward I knew something just didn't feel right.

The cruising spinnaker is a large sail made of very light material. Ours is contained within a sock. You lift the sock into place first, then raise sock to deploy the sail. As I dug this long, crinkling snake out of its bag, it spilled across the foredeck. Once underfoot, the material is as slippery as grease making the process of untangling the lines in a rolly seaway a difficult proposition. Two long lines must be isolated: the sheet and the control line which raises and lowers the sock. I attached the tack to the bow and led what I thought was an unencumbered sheet back to Sheryl in the cockpit. I went forward to connect the spinnaker halyard to the head of the sail and instructed Sheryl to raise it. It all looked good as a tube full of sail stretched from the bow to the top of the mast. I held the control line in my hand and started to gently pull.

The sock revealed the forward portion of the sail first and the crinkling sound got louder rather quickly. We were seeing 8-9 knots of apparent wind which, in retrospect, may be a little too much for flying our spinnaker. As the tack emerged from the sock, it became apparent that my control line was tangled slightly with the sheet. If I proceeded to reveal more sail, things would get ugly very quickly. With the snake now whipping its fan-like tail about 10 feet off the port side of the boat, I decided that maybe we should bring it down to untangle the lines.

I shouted back to Sheryl, in an effort to be heard over the boisterous sail, "Drop it!" My volume had suggested more urgency than intended and she very quickly lowered the silky fan-tailed snake. Portions plopped directly into the water before I could gather them on board.

With my heart beating loudly in my chest, I was thankful that I hadn't let too much of the sail out of the sock before noticing the problem. I also decided that one try was enough. With these winds, perhaps a different downwind technique was called for. I disconnected the head and tack, gathered up the lines, and stuffed it all back into its bag.

Next, we would try poling out the genoa (probably the technique we should have attempted first). Our whisker pole is mounted on the forward portion of the mast. It is connected to the mast at the top, where it runs along a track to lower it into place. The other end has a hook and pin which allow it to attach to the clew of the sail. When mounted on the mast, this pin also holds the pole in place. I discovered, much to my dismay, that it was held very firmly in place. Due largely to the fact that this pin has not been pulled in nearly two years, it was frozen.

Never fear, though, I have a solution. PB Blaster should take care of the problem; however, it often requires a little bit of soaking time. I suppose we can try it again tomorrow.