Beth and Evans

Most recent Blogs

19 September 2013 | Mills creek

06 August 2013 | smith cove

04 August 2013 | cradle cove

31 July 2013 | Broad cove, Islesboro Island

24 July 2013 | Maple Juice Cove

06 June 2013 | Maple Juice Cove, Maine

02 June 2013 | Onset, cape cod canal

20 May 2013 | Marion

18 May 2013 | Marion

16 May 2013 | Mattapoisett

10 May 2013 | Block ISland

02 May 2013 | Delaware Harbour of Refuge

16 April 2013 | Sassafras River

01 April 2013 | Cypress creek

06 March 2013 | Galesville, MD

20 August 2012 | South River, MD

09 August 2012 | Block Island

06 August 2012 | Shelburne, Nova Scotia

20 July 2012 | Louisburg

18 July 2012 | Lousiburg, Nova Scota

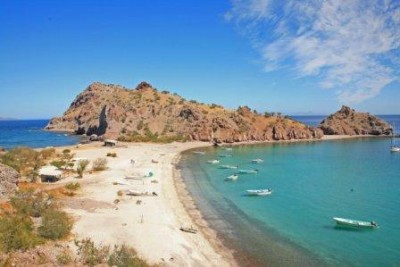

Cruising in the Sea of Cortez

03 March 2007 | La Paz, Baja California Sur, Mexico

Hola! We've just returned to La Paz after six weeks cruising the Sea of Cortez - the 700-mile long gulf sheltered from the Pacific Ocean by the narrow arm of the Baja peninsula. We spent our time in the southern third of the Sea, an area scattered with large and small islands, many anchorages, a few small towns and imposing scenery. Despite the fact that there must be close to 500 boats in the three large marinas and the anchorages in La Paz, we met only a handful of other cruisers while we were out, and we had many anchorages all to ourselves. That seems to be because most cruisers don't cruise the Sea in the winter. Many head south for the warmer waters of Puerto Vallarta and Acapulco, and most of the rest leave the boat on the hard in San Carlos halfway up the mainland side of the Sea or sit out the winter in La Paz. When we were preparing the boat to head out, we were warned repeatedly about the gale-force northerly winds, the cold nighttime temperatures and the 60-65 degree water. Given that the standard for our cruising aboard Hawk has been frequent storm-force winds, near-freezing nighttime temperatures and 40-50 degree water, it all sounded pretty good to us!

And winter cruising suited us just fine. The northerlies did blow at 25 knots or so for a couple of days about once every ten days. In between, the winds were light and going north we were able to enjoy some lovely sailing. When it came time to head south, we waited for those fresh northerlies and had some fast downwind runs on days when the morning forecast called for the "buffaloes to be running" - the steep, gray-humped waves that get kicked up quickly in the Gulf when the wind goes over 20 knots. The days were warm enough for shorts and tee-shirts, but the nights were cool enough for a wool blanket and a sound sleep. At any time but midday, we were comfortable walking ashore even when scrambling up loose scree and soft sand to reach the tops of the steep ridges that surrounded every anchorage. A light wetsuit allowed us to spend time in the emerald green waters. We had some heavy rain before we left La Paz, so the sparse scrub was blooming, spreading a thin patina of green over the arid brown dirt and red rocks of the desert. In the summer, the temperatures often reach 100 degrees or more, the winds are generally light and variable, the vegetation withdrawn into a state of suspended animation only one step from death. Yes, winter cruising was much more our style.

There is something almost unnerving about cruising over cobalt and emerald tropical water through a desert filled with cactus. Here life seems like an aberration on a land desperate for water, parched down to earth tones of brown, red and tan. In many places, the peaks along the Baja shoreline resemble nothing so much as exposed bones running in horizontal gray lines beneath the flat-topped mesas. Pyramids of reddish soil and rocks descend in inverted Vs from these bare gray rocks, the flesh sloughed off the skeleton by the slow work of gravity and the fast deluge of rain that comes but once or twice in a year. As the skeleton has been laid bare at the top of the peaks, so has the soft underbelly of the land been exposed where it joins the water. In many places, the rock has been undercut by the action of the waves into great curving walls of red, frozen undulations of smooth bare rock the exact negative of the force that created them.

The lack of human habitation and vegetation along with the exceptional quality of the light make it exceedingly difficult to judge scale or distance. There is a clarity to the light that reminds us of the high latitudes. While on watch, we will often sight a headland and assume we will be past it in an hour or so, but two hours later we will still be heading toward it and it will seem little larger than when we first sighted it, making us feel as if the headland were actually retreating from us. The exceptional clarity of the light allows us to see every detail of headlands that are 12, 15 or 20 miles away, and, in conjunction with their size and the lack of scale, makes them appear to be a third that distance from us. Often when we first sight a headland, it will appear to have an island off of it, but as we approach and the curvature of the earth lessens, a bridge of land will spring up between the headland and the island, and they will become one. On other days, the lightest of hazes hangs over everything like a thin gauze covering. It is barely perceptible, yet given the abnormal clarity we have become used to it has the affect of making things appear much further away than they actually are. On those days, we sometimes come too close to headlands and off lying rocks, thinking that we have left plenty of distance.

No one could call this land beautiful most of the time. Striking, perhaps. Stark and simple. But when the slanting rays of the late evening or early morning sun touch the rugged hills, they are totally transformed. The colors in the peaks seem to burst free from the surrounding soil, and look almost as if they exist as a halo over the land. Rose and pink, orange and gold seem to shimmer in the very air, turning the meanest scene of impoverished shacks, abandoned nets and beached pangas into something so beautiful our breath catches. We make an effort to be out on deck in the magical hour after the sun rises or before it sets, for at those times the scenery is almost surreal, the clarity heightened even more than usual, the color palette so strikingly original in comparison to the greens and blues of our youth.

Despite the beauty of its character, the Sea seems strangely empty and hauntingly bereft. Would we have felt this had we not been aware of the Sea's past, of the abundance that once existed in these waters and would have in some way made up for the barrenness of the land? Perhaps, but we will never be sure. There is a silence here that seems to ache, an emptiness that echoes with grief. Steinbeck's The Log of the Sea of Cortez tells the story of a voyage to nowhere for no good purpose, and recounts the thoughts the crew shared about the world and politics and war and humanity. Written in the 1940s, the book describes huge schools of dorado and tuna, tide pools full to bursting of anemones, sponges, corals, urchins, crabs, eels, starfish, worms - hundreds and hundreds of species of invertebrates. Steinbeck talks of catching lobster and crabs by the dozens. The teeming life he describes no longer exists. And he knows that the end is coming.

One of the last chapters in the book describes going aboard one of a dozen Japanese trawlers trawling for shrimp. They were proceeding twelve abreast down the middle of the Sea with overlapping dredges and pulling everything from the sea floor up to the boat. Steinbeck and his compatriots went aboard to collect specimens, and he described the wholesale slaughter that was going on:

"The dredge was out when we came aboard, but soon the cable drums began to turn, bringing in the heavy purse-dredge. The big scraper closed like a sack as it came up, and finally it deposited many tons of animals on deck - tons of shrimps, but also tons of fish of many varieties: sierras; pompano of several species; of the sharks, smooth-hounds and hammer-heads; eagle rays and butterfly rays; small tuna; catfish; puerco - tons of them. And there were bottom-samples with anemones and grass-like gorgonians. The sea bottom must have been scraped completely clean. The moment the net dropped open and spilled this mass of living things on the deck, the crew of Japanese went to work. Fish were thrown overboard immediately, and only the shrimps kept. The sea was littered with dead fish, and the gulls swarmed about eating them. Nearly all the fish were in a dying condition, and only a few recovered."

Steinbeck, back in the 1940s, says that the Japanese on those trawlers were good men doing a bad thing. Such is the story that we have seen and heard from Newfoundland to New Zealand, from the Sea of Cortez to the Arufura Sea, from Maine to Mauritania, from the Cape Verdes to the Cape of Good Hope. And here, it seems as if the work is very far advanced. We have seen only the occasional sea life: a ray in Honeymoon Cove; a dorado in Ballandra; a few whales south of San Juanico. The tide pools are overrun with a creature that Steinbeck mentions only once as a curiosity - a multi-legged nematode that resembles a cockroach. Hundreds scattered at our approach at San Juanico and Agua Verde when we walked among the tide pools.

The few small settlements located near the anchorages consist of little more than corrugated tin or concrete block shacks, many in the process of being rebuilt after Hurricane Marty a few years ago. Each small pueblo has a tienda, a tiny store that carries a limited variety of canned and packaged goods and a few fresh fruits and vegetables that have traveled for hours over sandy, dirt roads. Each pueblo also has a school and a church, and it is clear that these are where most of each community's money goes. The inhabitants have always made their living from the sea, but that has become increasingly difficult. The cruisers we meet who have been coming here for many years all say the same thing: "The Sea is dying. Each year we find fewer and fewer fish, see fewer and fewer whales. The local people cannot catch enough to feed their families." But the trawlers are still here, still trawling for shrimp, and now the only way the fishermen make any money.

Is it possible to feel the emptiness of a place and to know that emptiness is a gap left by the loss of millions and millions of creatures? Is it possible for a body of water to mourn for the life that once filled it to brimming? Is it possible to feel the loneliness of the creatures that remain? All of this seems fanciful, and yet we have been plagued with a strange sense of sadness and dislocation here, a sense of loss and of grief that we cannot account for within our own lives. It makes us hope that we are not good people doing a bad thing.

Take care of yourselves and of your little slice of the world, if you can.

Beth and Evans

s/v Hawk

And winter cruising suited us just fine. The northerlies did blow at 25 knots or so for a couple of days about once every ten days. In between, the winds were light and going north we were able to enjoy some lovely sailing. When it came time to head south, we waited for those fresh northerlies and had some fast downwind runs on days when the morning forecast called for the "buffaloes to be running" - the steep, gray-humped waves that get kicked up quickly in the Gulf when the wind goes over 20 knots. The days were warm enough for shorts and tee-shirts, but the nights were cool enough for a wool blanket and a sound sleep. At any time but midday, we were comfortable walking ashore even when scrambling up loose scree and soft sand to reach the tops of the steep ridges that surrounded every anchorage. A light wetsuit allowed us to spend time in the emerald green waters. We had some heavy rain before we left La Paz, so the sparse scrub was blooming, spreading a thin patina of green over the arid brown dirt and red rocks of the desert. In the summer, the temperatures often reach 100 degrees or more, the winds are generally light and variable, the vegetation withdrawn into a state of suspended animation only one step from death. Yes, winter cruising was much more our style.

There is something almost unnerving about cruising over cobalt and emerald tropical water through a desert filled with cactus. Here life seems like an aberration on a land desperate for water, parched down to earth tones of brown, red and tan. In many places, the peaks along the Baja shoreline resemble nothing so much as exposed bones running in horizontal gray lines beneath the flat-topped mesas. Pyramids of reddish soil and rocks descend in inverted Vs from these bare gray rocks, the flesh sloughed off the skeleton by the slow work of gravity and the fast deluge of rain that comes but once or twice in a year. As the skeleton has been laid bare at the top of the peaks, so has the soft underbelly of the land been exposed where it joins the water. In many places, the rock has been undercut by the action of the waves into great curving walls of red, frozen undulations of smooth bare rock the exact negative of the force that created them.

The lack of human habitation and vegetation along with the exceptional quality of the light make it exceedingly difficult to judge scale or distance. There is a clarity to the light that reminds us of the high latitudes. While on watch, we will often sight a headland and assume we will be past it in an hour or so, but two hours later we will still be heading toward it and it will seem little larger than when we first sighted it, making us feel as if the headland were actually retreating from us. The exceptional clarity of the light allows us to see every detail of headlands that are 12, 15 or 20 miles away, and, in conjunction with their size and the lack of scale, makes them appear to be a third that distance from us. Often when we first sight a headland, it will appear to have an island off of it, but as we approach and the curvature of the earth lessens, a bridge of land will spring up between the headland and the island, and they will become one. On other days, the lightest of hazes hangs over everything like a thin gauze covering. It is barely perceptible, yet given the abnormal clarity we have become used to it has the affect of making things appear much further away than they actually are. On those days, we sometimes come too close to headlands and off lying rocks, thinking that we have left plenty of distance.

No one could call this land beautiful most of the time. Striking, perhaps. Stark and simple. But when the slanting rays of the late evening or early morning sun touch the rugged hills, they are totally transformed. The colors in the peaks seem to burst free from the surrounding soil, and look almost as if they exist as a halo over the land. Rose and pink, orange and gold seem to shimmer in the very air, turning the meanest scene of impoverished shacks, abandoned nets and beached pangas into something so beautiful our breath catches. We make an effort to be out on deck in the magical hour after the sun rises or before it sets, for at those times the scenery is almost surreal, the clarity heightened even more than usual, the color palette so strikingly original in comparison to the greens and blues of our youth.

Despite the beauty of its character, the Sea seems strangely empty and hauntingly bereft. Would we have felt this had we not been aware of the Sea's past, of the abundance that once existed in these waters and would have in some way made up for the barrenness of the land? Perhaps, but we will never be sure. There is a silence here that seems to ache, an emptiness that echoes with grief. Steinbeck's The Log of the Sea of Cortez tells the story of a voyage to nowhere for no good purpose, and recounts the thoughts the crew shared about the world and politics and war and humanity. Written in the 1940s, the book describes huge schools of dorado and tuna, tide pools full to bursting of anemones, sponges, corals, urchins, crabs, eels, starfish, worms - hundreds and hundreds of species of invertebrates. Steinbeck talks of catching lobster and crabs by the dozens. The teeming life he describes no longer exists. And he knows that the end is coming.

One of the last chapters in the book describes going aboard one of a dozen Japanese trawlers trawling for shrimp. They were proceeding twelve abreast down the middle of the Sea with overlapping dredges and pulling everything from the sea floor up to the boat. Steinbeck and his compatriots went aboard to collect specimens, and he described the wholesale slaughter that was going on:

"The dredge was out when we came aboard, but soon the cable drums began to turn, bringing in the heavy purse-dredge. The big scraper closed like a sack as it came up, and finally it deposited many tons of animals on deck - tons of shrimps, but also tons of fish of many varieties: sierras; pompano of several species; of the sharks, smooth-hounds and hammer-heads; eagle rays and butterfly rays; small tuna; catfish; puerco - tons of them. And there were bottom-samples with anemones and grass-like gorgonians. The sea bottom must have been scraped completely clean. The moment the net dropped open and spilled this mass of living things on the deck, the crew of Japanese went to work. Fish were thrown overboard immediately, and only the shrimps kept. The sea was littered with dead fish, and the gulls swarmed about eating them. Nearly all the fish were in a dying condition, and only a few recovered."

Steinbeck, back in the 1940s, says that the Japanese on those trawlers were good men doing a bad thing. Such is the story that we have seen and heard from Newfoundland to New Zealand, from the Sea of Cortez to the Arufura Sea, from Maine to Mauritania, from the Cape Verdes to the Cape of Good Hope. And here, it seems as if the work is very far advanced. We have seen only the occasional sea life: a ray in Honeymoon Cove; a dorado in Ballandra; a few whales south of San Juanico. The tide pools are overrun with a creature that Steinbeck mentions only once as a curiosity - a multi-legged nematode that resembles a cockroach. Hundreds scattered at our approach at San Juanico and Agua Verde when we walked among the tide pools.

The few small settlements located near the anchorages consist of little more than corrugated tin or concrete block shacks, many in the process of being rebuilt after Hurricane Marty a few years ago. Each small pueblo has a tienda, a tiny store that carries a limited variety of canned and packaged goods and a few fresh fruits and vegetables that have traveled for hours over sandy, dirt roads. Each pueblo also has a school and a church, and it is clear that these are where most of each community's money goes. The inhabitants have always made their living from the sea, but that has become increasingly difficult. The cruisers we meet who have been coming here for many years all say the same thing: "The Sea is dying. Each year we find fewer and fewer fish, see fewer and fewer whales. The local people cannot catch enough to feed their families." But the trawlers are still here, still trawling for shrimp, and now the only way the fishermen make any money.

Is it possible to feel the emptiness of a place and to know that emptiness is a gap left by the loss of millions and millions of creatures? Is it possible for a body of water to mourn for the life that once filled it to brimming? Is it possible to feel the loneliness of the creatures that remain? All of this seems fanciful, and yet we have been plagued with a strange sense of sadness and dislocation here, a sense of loss and of grief that we cannot account for within our own lives. It makes us hope that we are not good people doing a bad thing.

Take care of yourselves and of your little slice of the world, if you can.

Beth and Evans

s/v Hawk

Comments

| Vessel Name: | Hawk |

Gallery not available