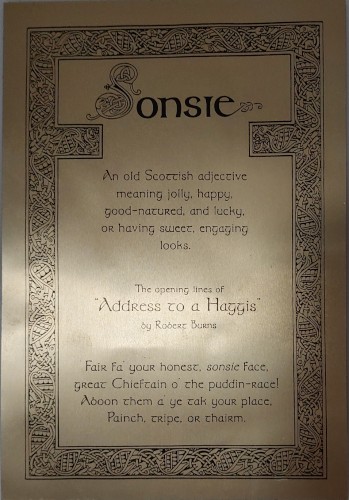

Owl & Pussycat / Sonsie of Victoria BC

Adventures aboard S/V Sonsie of Victoria

23 November 2021

31 December 2019

28 October 2019

27 October 2019

27 October 2019

27 October 2019

26 October 2019

26 October 2019

25 October 2019

25 October 2019

24 October 2019

24 October 2019

23 October 2019

22 October 2019

22 October 2019

21 October 2019

21 October 2019

19 October 2019

Terrible Storm #1

02 July 2014 | Passage from NZ to Fiji

July 2-3, 2014 Departure and the first terrible storm

Off the dock by 14:15, engine off by 14:30, sailing on a port reach with our workhorse staysail and second reefed main. Abeam Ninepin at 16:30, the sun was shining and the wind was dropping, blowing gently now at 15 knots. Were we just in the wind shadow of land or were the winds easing earlier than predicted? We mused. Picture the carefree, cosy scene of us together, laughing in the cockpit, having just enjoyed an early supper, Jim saying he may as well go down for a nap to start off our watch system.

Tinkle, tinkle, a curious little sound from the cabin. We look down and discover a broken mirror at the foot of the companionway steps. The symbolism cannot fail to send a tiny chill down one's spines. For the life of us we still can't figure out from where this little mirror spilled. Jim cleaned it up then came back up to the cockpit to say good night, but the wind snatched the words out of his mouth. The second we were beyond Ninepin rock, the wind blew 35. In a trice we furled the hankerchief of genoa in. By the time the main, second reefed, was brought down to third the wind was blowing fiercely at 45-50 knots. With just our staysail and a third-reefed main we were good to go for NZ Met Office's predicted 35 knots but the wind kept increasing to 55, gusting 65. The waves were 2m, choppy and unkindly. We were in for a bit of a ride!

Isabel made her way down to the cabin to make it more seaworthy. Nine months of coastal sailing had lulled us into making slightly less than ship tight preparations. Instant offshore conditions had caused a bit of disarray. She glanced over to the cabin settee which was set up as our passage berth. There on the pillow lay the carved wooden head-smashing club given to us by our friends in Samoa. It had jumped out of its storage place on the port handrail, flown across the cabin and landed square where Jim's head would have been had he gone down for his nap. That would have given him an awful wallop. Another little chill.

It was now dark and things were bouncy and unpleasant, to say the least. We were wishing we'd dropped the main instead of just third-reefing it, but we'd not expected such intense winds to whip up so quickly. We have sailed in pretty big blows on just staysail alone quite successfully. To drop the main, one of us has to go on deck to lash it to the boom. Jim called NZ's Taupo Maritime Radio to hear the latest weather report and they stuck with their previous forecast. However it was obvious that they were wrong, and that the Low had unexpectedly intensified by some margin. He also recorded our position with them.

It wouldn't be safe to go on deck in these conditions. Instead, to reduce canvas, we eased the main out as far as it would go, to spill out what wind we could.

Sonsie was charging along, heeling considerably. Waves broke over the starboard deck, smashing into and blowing out the plastic side windows of our dodger. Seawater streamed into the cockpit. The main halyard, staysail sheet, and reefing lines are all stored by the 5-clamp clutch atop the starboard cockpit. Some of the lines slid off into the gunnel which was swirling and coursing with water. Isabel, tethered, crouched on the lazarette, hip-deep in seawater, held on tight and fished all the lines out of the gunnel and heaped them on the cockpit floor.

We quickly rolled in the staysail in order to reduce canvas, but that made Sonsie less steerable. Indeed, our trusty Wendy Windvane immediately failed as the self-steering paddle promptly fell off. We activated the autohelm instead. Jim, tethered, leant down over the stern and retrieved the paddle. It was not possible in these dark, bouncy, wild conditions to reset it, so down into the lazarette it went.

All that long stormy night, Otto the autohelm was on faithful duty. While many sailors use theirs on a daily basis, we rarely use ours, so it was with great relief to find that when push came to shove, it was 100% dependable.

We rolled enough of the staysail out to make Sonsie more steerable, struggled to reattach some of the dodger plastic windows, then retreated below, Otto in control. In 50-70 knot winds, Sonsie heeled and galloped through the night, at a speed of 7-8 knots, on course! Down below, all sounded noisy and alarming with the boat slamming along through and into choppy waves with the rigging humming and thwacking all night. More waves spilled aboard and we could hear the flapping of plastic windows outside and sea water gurgling its way around the cockpit floor, out the drains back into the sea. It was a rollicking ride.

Isabel felt decidedly seasick as well as alarmed. Jim felt slightly better but not much. The option to heave-to did not appeal to us as we were too close to land. We were kicking ourselves for not dropping the main, and for believing the Brett area forecast!

Neither of us slept very well as fear kept our mouths dry and throats constricted. Visibility was poor; regardless, it would not have been wise to go into the cockpit to scan the horizon or check the radar for other traffic. We discussed our options for the morrow.

July 3

At 03:00 Jim wrote in the log:

In daylight:

¢ drop main/check rig

¢ self steering

¢ prep drogue

¢ run engine

By 09:00 we'd gone 113 NM since 17:00 the previous evening - a steady 7 knots, thankfully in the right direction! The wind wasn't easing however we determined to drop the main and lash it to the boom. But to make working on deck easier in these winds, still blowing 35-45 knots, max 60, and 3 metres waves, we decided to heave to. Sonsie doesn't always swing round responsively, so Jim turned on the engine to assist with the manoeuvre. Plus it is always wise to keep batteries topped up in any weather.

The cockpit was a wet scramble of equipment. All the lines Isabel had dragged out of the gunnel were in a messy heap on the cockpit floor. The remaining lines were tied in bundles in a wet soggy lump up on the cabintop by the clutch.

But dang! if there wasn't a line - the staysail traveller locking line - that had unknowingly splashed overboard at some later point, snaking along underwater, pulled down by its bundle, just waiting to be gobbled up by the prop. If only! was our constant lament for the next long while: If only we'd doublechecked that all lines were onboard! (But they always are; we're obsessive about flaking them and keeping them tidy and organized! They had never slopped overboard before, so it never occurred to us to check!) If only Jim had turned the wheel to port instead of to starboard, the line would never have caught. "If only" tears!

So now we had possible damage to the prop and brand new shaft, and no auxiliary propulsion.

That was Storm No. 1 and its aftermath.

The latest grib files we downloaded from via the HF radio showed that the system to the north was worsening so we decided our most prudent course was to hang back, and if not stay entirely out of that area, then at least only creep into the edge of the system.

We had four options:

- keep on sailing on staysail alone, but Sonsie moves at 6.5 knots in such winds and that would only serve to put us deeper into the system;

- furl in the staysail and lay ahull, but in these swells that would be hellishly uncomfortable and dangerous, as 3 metre, predicted to grow to 4-5 metres, waves could presumably be capable of rolling us;

- wave height predictions also made heaving to unappealing, even though we were now far enough from land;

- deploy our Jordan series drogue, to keep us stern-to the worst, in a stable configuration, and more or less "parked" where we were - drifting 1.5knots.

We liked the drogue idea. We lashed the main then waited for the (grib) predicted hour of relative calm (20knot winds) at noon, furled the staysail in, and threw the drogue into the sea: first the rope bridle which attaches to two padeyes at the stern, then a long thick warp (rope) followed by a line to which are sewn a hundred tiny parachutes, and then another such smaller line with a hundred slightly smaller parachutes, followed by a 15' length of chain to keep it below surface level. This lengthy contraption serves to slow a vessel's progress in the water, like a brake, extending a small vessel's footprint in the water in a way that breaking waves cannot roll or pitchpole or broach it - although they might occasionally "poop" it, or wash astern.

Our first time rigging it and it worked great. The drogue deployed without a hitch and worked a charm, although it initially made Sonsie more rollypolly than expected. The winds picked up again, but only to 35-45, and seas were 3 metres, so we began to second-guess ourselves: should we have deployed it? Stayed hove to? Sailed on under staysail alone?

Drogues are not only an effective way to slow down and keep a boat safe in a storm; they are a tool to use for crew rest. It's exhausting being anew at sea at the best of times, with the watch system and all the motion making every day, commonplace actions trickier than usual, requiring careful balance. Stir in seasickness. Throw in a storm and the increase in discomfort. Add in fear and sleeplessness, and you get pretty exhausted pretty darn quickly. Part of surviving at sea in difficult conditions is staying well rested, and making the right decisions. The drogue was just the ticket. We went down below to sleep.

At 15:00 local, 03:00 zulu, we joined in the roll call on Pacific Seafarers Net. How wonderful to speak to dedicated volunteers who care about the safety of far flung strangers!

By suppertime, we were definitely edging closer to the system. We congratulated ourselves on having made the right decision; we were safe. Jim slept for 12 hours, Isabel for 17.

[Photo courtesy of WallArc http://www.wallarc.com/wallpaper/view/486628]

Off the dock by 14:15, engine off by 14:30, sailing on a port reach with our workhorse staysail and second reefed main. Abeam Ninepin at 16:30, the sun was shining and the wind was dropping, blowing gently now at 15 knots. Were we just in the wind shadow of land or were the winds easing earlier than predicted? We mused. Picture the carefree, cosy scene of us together, laughing in the cockpit, having just enjoyed an early supper, Jim saying he may as well go down for a nap to start off our watch system.

Tinkle, tinkle, a curious little sound from the cabin. We look down and discover a broken mirror at the foot of the companionway steps. The symbolism cannot fail to send a tiny chill down one's spines. For the life of us we still can't figure out from where this little mirror spilled. Jim cleaned it up then came back up to the cockpit to say good night, but the wind snatched the words out of his mouth. The second we were beyond Ninepin rock, the wind blew 35. In a trice we furled the hankerchief of genoa in. By the time the main, second reefed, was brought down to third the wind was blowing fiercely at 45-50 knots. With just our staysail and a third-reefed main we were good to go for NZ Met Office's predicted 35 knots but the wind kept increasing to 55, gusting 65. The waves were 2m, choppy and unkindly. We were in for a bit of a ride!

Isabel made her way down to the cabin to make it more seaworthy. Nine months of coastal sailing had lulled us into making slightly less than ship tight preparations. Instant offshore conditions had caused a bit of disarray. She glanced over to the cabin settee which was set up as our passage berth. There on the pillow lay the carved wooden head-smashing club given to us by our friends in Samoa. It had jumped out of its storage place on the port handrail, flown across the cabin and landed square where Jim's head would have been had he gone down for his nap. That would have given him an awful wallop. Another little chill.

It was now dark and things were bouncy and unpleasant, to say the least. We were wishing we'd dropped the main instead of just third-reefing it, but we'd not expected such intense winds to whip up so quickly. We have sailed in pretty big blows on just staysail alone quite successfully. To drop the main, one of us has to go on deck to lash it to the boom. Jim called NZ's Taupo Maritime Radio to hear the latest weather report and they stuck with their previous forecast. However it was obvious that they were wrong, and that the Low had unexpectedly intensified by some margin. He also recorded our position with them.

It wouldn't be safe to go on deck in these conditions. Instead, to reduce canvas, we eased the main out as far as it would go, to spill out what wind we could.

Sonsie was charging along, heeling considerably. Waves broke over the starboard deck, smashing into and blowing out the plastic side windows of our dodger. Seawater streamed into the cockpit. The main halyard, staysail sheet, and reefing lines are all stored by the 5-clamp clutch atop the starboard cockpit. Some of the lines slid off into the gunnel which was swirling and coursing with water. Isabel, tethered, crouched on the lazarette, hip-deep in seawater, held on tight and fished all the lines out of the gunnel and heaped them on the cockpit floor.

We quickly rolled in the staysail in order to reduce canvas, but that made Sonsie less steerable. Indeed, our trusty Wendy Windvane immediately failed as the self-steering paddle promptly fell off. We activated the autohelm instead. Jim, tethered, leant down over the stern and retrieved the paddle. It was not possible in these dark, bouncy, wild conditions to reset it, so down into the lazarette it went.

All that long stormy night, Otto the autohelm was on faithful duty. While many sailors use theirs on a daily basis, we rarely use ours, so it was with great relief to find that when push came to shove, it was 100% dependable.

We rolled enough of the staysail out to make Sonsie more steerable, struggled to reattach some of the dodger plastic windows, then retreated below, Otto in control. In 50-70 knot winds, Sonsie heeled and galloped through the night, at a speed of 7-8 knots, on course! Down below, all sounded noisy and alarming with the boat slamming along through and into choppy waves with the rigging humming and thwacking all night. More waves spilled aboard and we could hear the flapping of plastic windows outside and sea water gurgling its way around the cockpit floor, out the drains back into the sea. It was a rollicking ride.

Isabel felt decidedly seasick as well as alarmed. Jim felt slightly better but not much. The option to heave-to did not appeal to us as we were too close to land. We were kicking ourselves for not dropping the main, and for believing the Brett area forecast!

Neither of us slept very well as fear kept our mouths dry and throats constricted. Visibility was poor; regardless, it would not have been wise to go into the cockpit to scan the horizon or check the radar for other traffic. We discussed our options for the morrow.

July 3

At 03:00 Jim wrote in the log:

In daylight:

¢ drop main/check rig

¢ self steering

¢ prep drogue

¢ run engine

By 09:00 we'd gone 113 NM since 17:00 the previous evening - a steady 7 knots, thankfully in the right direction! The wind wasn't easing however we determined to drop the main and lash it to the boom. But to make working on deck easier in these winds, still blowing 35-45 knots, max 60, and 3 metres waves, we decided to heave to. Sonsie doesn't always swing round responsively, so Jim turned on the engine to assist with the manoeuvre. Plus it is always wise to keep batteries topped up in any weather.

The cockpit was a wet scramble of equipment. All the lines Isabel had dragged out of the gunnel were in a messy heap on the cockpit floor. The remaining lines were tied in bundles in a wet soggy lump up on the cabintop by the clutch.

But dang! if there wasn't a line - the staysail traveller locking line - that had unknowingly splashed overboard at some later point, snaking along underwater, pulled down by its bundle, just waiting to be gobbled up by the prop. If only! was our constant lament for the next long while: If only we'd doublechecked that all lines were onboard! (But they always are; we're obsessive about flaking them and keeping them tidy and organized! They had never slopped overboard before, so it never occurred to us to check!) If only Jim had turned the wheel to port instead of to starboard, the line would never have caught. "If only" tears!

So now we had possible damage to the prop and brand new shaft, and no auxiliary propulsion.

That was Storm No. 1 and its aftermath.

The latest grib files we downloaded from via the HF radio showed that the system to the north was worsening so we decided our most prudent course was to hang back, and if not stay entirely out of that area, then at least only creep into the edge of the system.

We had four options:

- keep on sailing on staysail alone, but Sonsie moves at 6.5 knots in such winds and that would only serve to put us deeper into the system;

- furl in the staysail and lay ahull, but in these swells that would be hellishly uncomfortable and dangerous, as 3 metre, predicted to grow to 4-5 metres, waves could presumably be capable of rolling us;

- wave height predictions also made heaving to unappealing, even though we were now far enough from land;

- deploy our Jordan series drogue, to keep us stern-to the worst, in a stable configuration, and more or less "parked" where we were - drifting 1.5knots.

We liked the drogue idea. We lashed the main then waited for the (grib) predicted hour of relative calm (20knot winds) at noon, furled the staysail in, and threw the drogue into the sea: first the rope bridle which attaches to two padeyes at the stern, then a long thick warp (rope) followed by a line to which are sewn a hundred tiny parachutes, and then another such smaller line with a hundred slightly smaller parachutes, followed by a 15' length of chain to keep it below surface level. This lengthy contraption serves to slow a vessel's progress in the water, like a brake, extending a small vessel's footprint in the water in a way that breaking waves cannot roll or pitchpole or broach it - although they might occasionally "poop" it, or wash astern.

Our first time rigging it and it worked great. The drogue deployed without a hitch and worked a charm, although it initially made Sonsie more rollypolly than expected. The winds picked up again, but only to 35-45, and seas were 3 metres, so we began to second-guess ourselves: should we have deployed it? Stayed hove to? Sailed on under staysail alone?

Drogues are not only an effective way to slow down and keep a boat safe in a storm; they are a tool to use for crew rest. It's exhausting being anew at sea at the best of times, with the watch system and all the motion making every day, commonplace actions trickier than usual, requiring careful balance. Stir in seasickness. Throw in a storm and the increase in discomfort. Add in fear and sleeplessness, and you get pretty exhausted pretty darn quickly. Part of surviving at sea in difficult conditions is staying well rested, and making the right decisions. The drogue was just the ticket. We went down below to sleep.

At 15:00 local, 03:00 zulu, we joined in the roll call on Pacific Seafarers Net. How wonderful to speak to dedicated volunteers who care about the safety of far flung strangers!

By suppertime, we were definitely edging closer to the system. We congratulated ourselves on having made the right decision; we were safe. Jim slept for 12 hours, Isabel for 17.

[Photo courtesy of WallArc http://www.wallarc.com/wallpaper/view/486628]

Comments

| Vessel Name: | Sonsie of Victoria |

| Vessel Make/Model: | Southern Cross 39' |

| Hailing Port: | Piers Island BC |

| Crew: | Jim Merritt & Isabel Bliss |

| Extra: | A long ago blog featuring some of Sonsie's marvelous adventures |

Gallery not available

Who: Jim Merritt & Isabel Bliss

Port: Piers Island BC