Profile

Who: Kimball Corson. Text and Photos not disclaimed or that are obviously not mine are copyright (c) Kimball Corson 2004-2016

Port: Lake Pleasant, AZ

Altaira Wandering the Oceans

Favorites

- 7 Seas Cruising Association

- American Sailing Association

- Buoyweather Service

- CDC Traveler's Heath Advisories

- Cruiser Log venue

- Cruisers Forum

- Cruising Club of America

- Cruising Resources

- Cruising World Magazine

- Earthrace World Record

- Economic and Financial Indicators

- Economist Magazine

- Equipmment and Boat Reviews

- Float Plan Form

- Greenpeace Int'l

- Grib File Access

- Heavy Weather Sailing

- IMS Certificates

- Inland Travel: Expedia

- Intrade Prediction Markets

- Latitude 38

- London Financial Times

- Marine Books and Charts

- Marine Radios

- Nature Conservancy for Oceans

- New York Times

- NOAA Hurricane Analysis

- NOAA Weather Forecasts

- Noonsite, World Cruisng Info

- Ocean Cruising Club

- Overseas Mail Forwarding Services

- Practical Sailor Magazine

- RGE Economic Monitor

- Sail Gear Source I

- Sail Gear Source II

- Sail Gear Source III

- Sail Gear Source IV

- Sailboat Selection for Offshore Use

- Sailboats for Sale

- Sailing Items Sources Links

- SailMail (Marine Radio)

- Sailnet Sailing Information

- Seeking Alpha

- Tide & Current Program

- Tide Prediction Programs

- Tides & Currents

- TruthDig in the News

- U.S. Sailing Association

- Univ of Chicago Law Faculty Blog

- US State Dept Travel Advisories

- Voyage Planning (with pilot charts)

- Wall Street Journal

- Washington Post

- Weather.com

- Weather: MagicSeaweed

- Weather: Wetsand

- WinLink (Ham Radio)

- World Clock + Time Zones

09 April 2018 | Pago Pago, American Samoa

10 March 2018 | Pago Pago, American Samoa

10 March 2018 | Pago Pago, American Samoa

10 March 2018 | Pago Pago, American Samoa

22 August 2017 | Pago Pago, American Samoa

22 August 2017 | Pago Pago, American Samoa

22 August 2017 | Pago Pago, American Samoa

22 August 2017 | Pago Pago, American Samoa

22 August 2017 | Pago Pago, American Samoa

22 August 2017 | Pago Pago, American Samoa

22 August 2017 | Pago Pago, American Samoa

22 August 2017 | Pago Pago, American Samoa

22 August 2017 | Pago Pago, American Samoa

22 August 2017 | Pago Pago, American Samoa

22 August 2017 | Pago Pago, American Samoa

22 August 2017 | Pago Pago, American Samoa

22 August 2017 | Pago Pago, American Samoa

22 August 2017 | Pago Pago, American Samoa

22 August 2017 | Pago Pago, American Samoa

09 August 2017 | Pago Pago, American Samoa

A Critique of Friedman’s Core Analysis on Government Spending

23 October 2016 | Pago Pago, American Samoa

Kimball Corson

You must understand the center of Friedman's teaching career was in the mid-fifties when income inequality was not an issue and hoarding was much less of an issue. Friedman never focused on Keynes' idea of liquidity preference and the liquidity trap at all in all the classes I took from him for the four years when I took all of his courses (1965-1969). He talked only about the demand for money, which I argued, as Keynes did, was really a demand for liquidity not just money. That was a close as he got. Nobel laureate Robert Mundell, America's most articulate Keynesian (who later developed supply side economics, just as a mental exercise) was teaching at Chicago at that time and he covered those topics, but only very briefly.

Hoarding was not a serious problem then as it had been when Keynes wrote the "General Theory" in the thirties during the great depression. Consequently, Says' Law came close to applying in the 50's and 60's so GPD = National income = Y = C + I when S = I which is what is still what is taught in basic mainstream economics courses with interest rates as the equilibrating variable on S = I.

Later, as now, with hugely excessive income inequality, hoarding by corporations and the rich is a huge problem so GDP is not equal to Y and Y= C - H where H = S - I. Apple alone holds 181 billion in cash. And again, income hoarded is all income not spent on current consumption or current real, new investment, what we must have for GDP to = Y. The rich have so much money they can't spend it all while those much poorer spend every cent they can get (and sometimes more, using pay day loans). Hoarding occurs, as Keynes explained, when people, mainly the rich, have a high preference for liquidity and stick hoarded money in secondary financial markets and cash where they can get it to cash very quickly. Real investment ties money up in business expansion and new plant and equipment and does not satisfy high liquidity preference. So a high preference for liquidity decreases both C and I.

Next, we must keep in mind, Friedman's political biases. He hated for the government to interfere in the economy and its markets and publicly espoused the view that markets worked correctly and mostly flawlessly. However, he told his graduate students he knew markets made mistakes, but he believed regulators could not correct or prevent them because they were captives of their industries - namely, bought off. So Friedman was at heart and mistakenly, a core enemy of Keynesian stimulus spending and economic intervention, EXCEPT, he conceded the Fed had to interfere and intervene to keep the economy on track by regulating the money supply. This is the background needed to understand Friedman. Now turning to his essay.--

Fallacy: Government Spending and

Deficits Stimulate the Economy

by Milton Friedman

An increase in government spending clearly benefits the individuals who receive the additional spending. Considered by itself, it looks as if the additional spending is a stimulus to the economy.

But that is hardly the end of the story. We have to ask where the government gets the money it spends. The government can get the money in only three ways: increased taxes; borrowing from the public; creating new money. Let us examine each of these in turn.

[This is incorrect. Government expenditures are based on credit and the totals try to follow budgeted allotments. The government later has to fund such purchases by tax revenues or borrowing. It cannot or does not create new money. Only the Fed does that.]

■Additional taxation. In this situation, the dollar cost to the persons who pay the taxes is exactly equal to the dollar gain to the persons who receive the spending. It looks like a washout.

[This is misleading. For the economy it is not a washout. If idle hoarded money is taxed and spent on real consumption or investment, it is a net gain to the economy and to all those involved.]

Getting the extra taxes, however, requires raising the rate of taxation. As a result, the taxpayer gets to keep less of each dollar earned or received as a return on investment [true], which reduces his or her incentive to work and to save [false]. The resulting reduction in effort or in savings is a hidden cost of the extra spending. [Not true] Far from being a stimulus to the economy, extra spending financed through higher taxes is a drag on the economy. [false]

[This analysis is basically wrong; the rich who hoard simply have their cash hoards taxed a bit and drawn down, but given their strong preference for highly liquid cash and near cash, they simply work harder to reestablish those cash hoards. (I have done this myself when in the 1%.)]

This does not mean that the extra spending can never be justified. However, it can only be justified on the ground that the benefit to the people who receive the spending, or to the community from the activity to be financed by the spending, is greater than the direct harm to the taxpayers plus the hidden cost. It cannot be justified as a way to stimulate the overall economy.

[No hidden cost. Gain analysis must include greater work effort to reestablish preferred cash or near cash levels. A beneficial double whammy. Otherwise, Friedman is correct here.]

■ Government spending financed by borrowing from the public. Individuals who purchase the securities that finance the additional expenditure would have done something else with the money. [Yes, hoard much of it in cash and secondary markets instead of spending it all on consumption and real investment.] If they had not purchased the government securities, they presumably would have purchased private securities that would have financed private investment. [Assumes original stock offerings which is rarely the case. Most hoarded money goes into secondary financial markets to push up stock prices] In other words, government spending crowds out private investment. [Not at all true.] At this level, it is again a washout: those who receive the extra government spending benefit, but the private investors, who are deprived of the same amount of funds, lose. [false. See analysis above.]

But again, that is too simple a story. [true] The overall effect is an increase in the demand for loanable funds, which tends to raise interest rates. [No. hoarders do not borrow to hoard more. They mostly work harder to reestablish their cash and near cash levels to meet their preferences.] The rise in interest rates [There is no such rise. Yields and interest rates are depressed by hoarding pushing up stock and bond prices in secondary financial markets.] discourages private demand for funds to make way for the increased government demand. [No. rates are pushed down as I explain (what we observe now) and we get any investment gain from it which is small because hoarders do not want new real investments so far removed from cash.] Thus, there is a hidden cost in the form of a lowered stock of productive capital and lower future income. [false, there might even be a gain from depressed yields and rates.]

The Keynesian view that the spending is stimulative assumes that the funds the government borrows would not otherwise have been invested in the private capital market [usually true], but came simply from cash held in hoards by individuals from under the mattress [True, but Friedman misunderstands hoarding and liquidity preference as I have explained them]. In addition, it assumes that there are unemployed resources that can readily be brought into the work force by activating the excess funds held by individuals, without raising prices or wages [true].

That is a possibility in some special cases, such as the Great Depression in the 1930s, when there had been a major reduction in total output and prices were very far from their equilibrium level. [True then and true now too, with such great income inequality and great hoarding by the rich.] More generally, however, theory suggests and experience confirms that government spending financed by borrowing from the public does not provide a stimulus to the economy [Not true in US or most foreign countries now.]

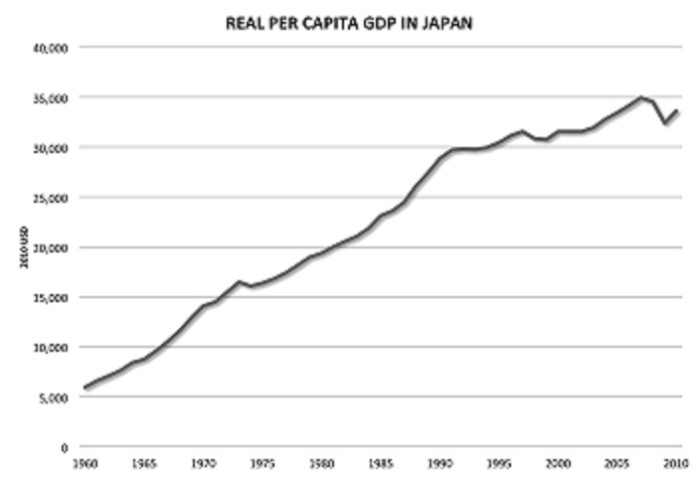

Japan provides a dramatic recent example. During the 1990s, the Japanese economy was depressed. The government tried repeated fiscals stimulus packages, each involving increases in government spending financed by borrowing. Yet -- or maybe therefore -- the Japanese economy remained depressed. [Not true. Look at graph of Japanese per capita real income growth and it has been monotonically and steadily up, even through the 1990's, except for a dip later. See my graph in comments.]

■ Government spending financed by creating new money. In this case, there is no first-round private offset to the government spending. It looks as if it is clearly stimulative, and it is. The question is: What is doing the stimulating? Is it the government spending, which in the previous two cases was not stimulative? Or is it the increase in the quantity of money by which the government spending is financed? [Government spending in the US is never financed by newly created money. Only the Fed can increase the money supply which it does by open market operations and QE.]

Suppose the monetary authorities simply added to the money supply without any change in government spending. (They [the Fed, actually] could do so by purchasing government securities on the market.) The additional demand for government securities would raise their price, which is equivalent to a reduction in the rate of interest. If the sellers of the securities simply put the new money under the mattress [or in secondary markets, driving up prices], that would [mostly be the] end the story and there would be no stimulus. They are far more likely, however, to use the money for some alternative investment, or to spend on consumption [or some mix of all of the above]. That would lead to exactly the same additional spending as using the money for government spending, but the extra spending would be in the private economy, not the public sector. [Yes, for the EXTRA spending, but the total is increased because of the original increase in government expenditure].

Digging deeper, the extra spending will initially be reflected in some combination of increased output and increased prices. The exact division will vary greatly from time to time, depending on the state of the economy and on whether the extra spending was or was not anticipated. [mostly output] If the initial situation were one of an economy roughly at its capacity level with reasonably full employment, a temporary stimulus to more production would be followed by a higher price level. [True] After the price level had adjusted, the real economy would be back where it had started, unless there were further increases in money, setting off an inflationary spiral [true, but just more inflation, not necessarily a spiral].

On the other hand, if the initial position were one of deep recession with unemployed resources, a much larger fraction of the increase in spending would be absorbed by an increase in employment and output, and a much smaller fraction by a rise in prices. [True] Similarly, if the initial situation were one of incipient inflation, even the initial effect might be to produce inflation. [True]

■ Confusion between monetary stimulus and fiscal stimulus. The fallacy that government spending and deficits stimulate the economy has gained credibility because the extra spending is so often financed by creating new money. [Not a fallacy, as I have shown] In that case, fiscal policy (changes in government spending and taxation) and monetary policy (changes in the quantity of money) are both in play and it is easy to attribute the effects of monetary policy to the effects of fiscal policy.

In order to get empirical evidence on the separate effects of fiscal and monetary policy, it is necessary to find episodes in which fiscal and monetary policy are moving in opposite directions, or one is neutral while the other is not. The example of Japan in the 1990s noted earlier is one such episode. In that case, monetary policy was repressive or at best neutral and fiscal stimuli programs were ineffective. [No. Not true. See chart.]

Over the course of years, I have studied a number of similar episodes both in the United States and around the world. In every case, fiscal policy intended to be expansionary was expansionary if and only if monetary policy was accommodating. [True most of the time, but not if and only if, as I indicate. Hoarded money put back in circulation against goods and services is a big exception] This empirical evidence is consistent with the theoretical analysis of the preceding section

Hoarding was not a serious problem then as it had been when Keynes wrote the "General Theory" in the thirties during the great depression. Consequently, Says' Law came close to applying in the 50's and 60's so GPD = National income = Y = C + I when S = I which is what is still what is taught in basic mainstream economics courses with interest rates as the equilibrating variable on S = I.

Later, as now, with hugely excessive income inequality, hoarding by corporations and the rich is a huge problem so GDP is not equal to Y and Y= C - H where H = S - I. Apple alone holds 181 billion in cash. And again, income hoarded is all income not spent on current consumption or current real, new investment, what we must have for GDP to = Y. The rich have so much money they can't spend it all while those much poorer spend every cent they can get (and sometimes more, using pay day loans). Hoarding occurs, as Keynes explained, when people, mainly the rich, have a high preference for liquidity and stick hoarded money in secondary financial markets and cash where they can get it to cash very quickly. Real investment ties money up in business expansion and new plant and equipment and does not satisfy high liquidity preference. So a high preference for liquidity decreases both C and I.

Next, we must keep in mind, Friedman's political biases. He hated for the government to interfere in the economy and its markets and publicly espoused the view that markets worked correctly and mostly flawlessly. However, he told his graduate students he knew markets made mistakes, but he believed regulators could not correct or prevent them because they were captives of their industries - namely, bought off. So Friedman was at heart and mistakenly, a core enemy of Keynesian stimulus spending and economic intervention, EXCEPT, he conceded the Fed had to interfere and intervene to keep the economy on track by regulating the money supply. This is the background needed to understand Friedman. Now turning to his essay.--

Fallacy: Government Spending and

Deficits Stimulate the Economy

by Milton Friedman

An increase in government spending clearly benefits the individuals who receive the additional spending. Considered by itself, it looks as if the additional spending is a stimulus to the economy.

But that is hardly the end of the story. We have to ask where the government gets the money it spends. The government can get the money in only three ways: increased taxes; borrowing from the public; creating new money. Let us examine each of these in turn.

[This is incorrect. Government expenditures are based on credit and the totals try to follow budgeted allotments. The government later has to fund such purchases by tax revenues or borrowing. It cannot or does not create new money. Only the Fed does that.]

■Additional taxation. In this situation, the dollar cost to the persons who pay the taxes is exactly equal to the dollar gain to the persons who receive the spending. It looks like a washout.

[This is misleading. For the economy it is not a washout. If idle hoarded money is taxed and spent on real consumption or investment, it is a net gain to the economy and to all those involved.]

Getting the extra taxes, however, requires raising the rate of taxation. As a result, the taxpayer gets to keep less of each dollar earned or received as a return on investment [true], which reduces his or her incentive to work and to save [false]. The resulting reduction in effort or in savings is a hidden cost of the extra spending. [Not true] Far from being a stimulus to the economy, extra spending financed through higher taxes is a drag on the economy. [false]

[This analysis is basically wrong; the rich who hoard simply have their cash hoards taxed a bit and drawn down, but given their strong preference for highly liquid cash and near cash, they simply work harder to reestablish those cash hoards. (I have done this myself when in the 1%.)]

This does not mean that the extra spending can never be justified. However, it can only be justified on the ground that the benefit to the people who receive the spending, or to the community from the activity to be financed by the spending, is greater than the direct harm to the taxpayers plus the hidden cost. It cannot be justified as a way to stimulate the overall economy.

[No hidden cost. Gain analysis must include greater work effort to reestablish preferred cash or near cash levels. A beneficial double whammy. Otherwise, Friedman is correct here.]

■ Government spending financed by borrowing from the public. Individuals who purchase the securities that finance the additional expenditure would have done something else with the money. [Yes, hoard much of it in cash and secondary markets instead of spending it all on consumption and real investment.] If they had not purchased the government securities, they presumably would have purchased private securities that would have financed private investment. [Assumes original stock offerings which is rarely the case. Most hoarded money goes into secondary financial markets to push up stock prices] In other words, government spending crowds out private investment. [Not at all true.] At this level, it is again a washout: those who receive the extra government spending benefit, but the private investors, who are deprived of the same amount of funds, lose. [false. See analysis above.]

But again, that is too simple a story. [true] The overall effect is an increase in the demand for loanable funds, which tends to raise interest rates. [No. hoarders do not borrow to hoard more. They mostly work harder to reestablish their cash and near cash levels to meet their preferences.] The rise in interest rates [There is no such rise. Yields and interest rates are depressed by hoarding pushing up stock and bond prices in secondary financial markets.] discourages private demand for funds to make way for the increased government demand. [No. rates are pushed down as I explain (what we observe now) and we get any investment gain from it which is small because hoarders do not want new real investments so far removed from cash.] Thus, there is a hidden cost in the form of a lowered stock of productive capital and lower future income. [false, there might even be a gain from depressed yields and rates.]

The Keynesian view that the spending is stimulative assumes that the funds the government borrows would not otherwise have been invested in the private capital market [usually true], but came simply from cash held in hoards by individuals from under the mattress [True, but Friedman misunderstands hoarding and liquidity preference as I have explained them]. In addition, it assumes that there are unemployed resources that can readily be brought into the work force by activating the excess funds held by individuals, without raising prices or wages [true].

That is a possibility in some special cases, such as the Great Depression in the 1930s, when there had been a major reduction in total output and prices were very far from their equilibrium level. [True then and true now too, with such great income inequality and great hoarding by the rich.] More generally, however, theory suggests and experience confirms that government spending financed by borrowing from the public does not provide a stimulus to the economy [Not true in US or most foreign countries now.]

Japan provides a dramatic recent example. During the 1990s, the Japanese economy was depressed. The government tried repeated fiscals stimulus packages, each involving increases in government spending financed by borrowing. Yet -- or maybe therefore -- the Japanese economy remained depressed. [Not true. Look at graph of Japanese per capita real income growth and it has been monotonically and steadily up, even through the 1990's, except for a dip later. See my graph in comments.]

■ Government spending financed by creating new money. In this case, there is no first-round private offset to the government spending. It looks as if it is clearly stimulative, and it is. The question is: What is doing the stimulating? Is it the government spending, which in the previous two cases was not stimulative? Or is it the increase in the quantity of money by which the government spending is financed? [Government spending in the US is never financed by newly created money. Only the Fed can increase the money supply which it does by open market operations and QE.]

Suppose the monetary authorities simply added to the money supply without any change in government spending. (They [the Fed, actually] could do so by purchasing government securities on the market.) The additional demand for government securities would raise their price, which is equivalent to a reduction in the rate of interest. If the sellers of the securities simply put the new money under the mattress [or in secondary markets, driving up prices], that would [mostly be the] end the story and there would be no stimulus. They are far more likely, however, to use the money for some alternative investment, or to spend on consumption [or some mix of all of the above]. That would lead to exactly the same additional spending as using the money for government spending, but the extra spending would be in the private economy, not the public sector. [Yes, for the EXTRA spending, but the total is increased because of the original increase in government expenditure].

Digging deeper, the extra spending will initially be reflected in some combination of increased output and increased prices. The exact division will vary greatly from time to time, depending on the state of the economy and on whether the extra spending was or was not anticipated. [mostly output] If the initial situation were one of an economy roughly at its capacity level with reasonably full employment, a temporary stimulus to more production would be followed by a higher price level. [True] After the price level had adjusted, the real economy would be back where it had started, unless there were further increases in money, setting off an inflationary spiral [true, but just more inflation, not necessarily a spiral].

On the other hand, if the initial position were one of deep recession with unemployed resources, a much larger fraction of the increase in spending would be absorbed by an increase in employment and output, and a much smaller fraction by a rise in prices. [True] Similarly, if the initial situation were one of incipient inflation, even the initial effect might be to produce inflation. [True]

■ Confusion between monetary stimulus and fiscal stimulus. The fallacy that government spending and deficits stimulate the economy has gained credibility because the extra spending is so often financed by creating new money. [Not a fallacy, as I have shown] In that case, fiscal policy (changes in government spending and taxation) and monetary policy (changes in the quantity of money) are both in play and it is easy to attribute the effects of monetary policy to the effects of fiscal policy.

In order to get empirical evidence on the separate effects of fiscal and monetary policy, it is necessary to find episodes in which fiscal and monetary policy are moving in opposite directions, or one is neutral while the other is not. The example of Japan in the 1990s noted earlier is one such episode. In that case, monetary policy was repressive or at best neutral and fiscal stimuli programs were ineffective. [No. Not true. See chart.]

Over the course of years, I have studied a number of similar episodes both in the United States and around the world. In every case, fiscal policy intended to be expansionary was expansionary if and only if monetary policy was accommodating. [True most of the time, but not if and only if, as I indicate. Hoarded money put back in circulation against goods and services is a big exception] This empirical evidence is consistent with the theoretical analysis of the preceding section

Comments

| Vessel Name: | Altaira |

| Vessel Make/Model: | A Fair Weather Mariner 39 is a fast (PHRF 132), heavily ballasted (43%), high-aspect (6:1), stiff, comfortable, offshore performance cruiser by Bob Perry that goes to wind well (30 deg w/ good headway) and is also good up and down the Beaufort scale. |

| Hailing Port: | Lake Pleasant, AZ |

| Crew: | Kimball Corson. Text and Photos not disclaimed or that are obviously not mine are copyright (c) Kimball Corson 2004-2016 |

| About: | |

| Extra: |

Altaira's Photos - Main

No items in this gallery.

Profile

Who: Kimball Corson. Text and Photos not disclaimed or that are obviously not mine are copyright (c) Kimball Corson 2004-2016

Port: Lake Pleasant, AZ

Altaira Wandering the Oceans

Favorites

- 7 Seas Cruising Association

- American Sailing Association

- Buoyweather Service

- CDC Traveler's Heath Advisories

- Cruiser Log venue

- Cruisers Forum

- Cruising Club of America

- Cruising Resources

- Cruising World Magazine

- Earthrace World Record

- Economic and Financial Indicators

- Economist Magazine

- Equipmment and Boat Reviews

- Float Plan Form

- Greenpeace Int'l

- Grib File Access

- Heavy Weather Sailing

- IMS Certificates

- Inland Travel: Expedia

- Intrade Prediction Markets

- Latitude 38

- London Financial Times

- Marine Books and Charts

- Marine Radios

- Nature Conservancy for Oceans

- New York Times

- NOAA Hurricane Analysis

- NOAA Weather Forecasts

- Noonsite, World Cruisng Info

- Ocean Cruising Club

- Overseas Mail Forwarding Services

- Practical Sailor Magazine

- RGE Economic Monitor

- Sail Gear Source I

- Sail Gear Source II

- Sail Gear Source III

- Sail Gear Source IV

- Sailboat Selection for Offshore Use

- Sailboats for Sale

- Sailing Items Sources Links

- SailMail (Marine Radio)

- Sailnet Sailing Information

- Seeking Alpha

- Tide & Current Program

- Tide Prediction Programs

- Tides & Currents

- TruthDig in the News

- U.S. Sailing Association

- Univ of Chicago Law Faculty Blog

- US State Dept Travel Advisories

- Voyage Planning (with pilot charts)

- Wall Street Journal

- Washington Post

- Weather.com

- Weather: MagicSeaweed

- Weather: Wetsand

- WinLink (Ham Radio)

- World Clock + Time Zones