28 December 2010

10 October 2010

10 October 2010 | Niue

10 October 2010 | Nowhereland

10 October 2010 | Cook Islands

22 September 2010 | Rarotonga, Cook Islands

04 September 2010 | Rarotonga

22 August 2010

29 July 2010 | Tuamotus

10 July 2010 | Nuku Hiva

04 May 2010 | Oahu for one more day

Tonga, New Zealand, and Home!

28 December 2010

Kevin

After writing about Niue back in October, my blog-motivation faltered, and I failed to post entries for Tonga and New Zealand. For those of you who then assumed that we died in a cave in Niue: ALL IS WELL!

After spending about five weeks in Tonga, the crew of the Shannon made the leap down to New Zealand with a quick stop at Minerva Reef. We arrived in Opua, NZ on November 9th after an exceptionally nice easy passage. Whew!

Christina met us at the dock in Opua (along with couple other good friends) and we spent some time cruising the Bay of Islands and the Tutukaka Coast in their company. (Let's just say that 8 people aboard is about all Shannon can comfortably handle!).

On November 29th, we hauled Shannon out of the water at Norsand Boatyard in Whangerei, NZ. There she'll sit in her cradle until we're ready to sail her again, which will probably end up being the spring of '12. Ken and Alina are back in Hawaii, and Christina and I are currently back in Montana for Christmas, enjoying some family time and all the good x-country skiing.

I hope to write an account of our experiences in Tonga and New Zealand before they fade from memory, so just because the Shannon isn't sailing anymore doesn't mean you shouldn't check the blog a few more times!

Christina and I will be heading back to Hawaii on Jan 13th to start work and replenish our severely depleated coffers!

Hope everyone had a great Holiday. Happy New Years!

After spending about five weeks in Tonga, the crew of the Shannon made the leap down to New Zealand with a quick stop at Minerva Reef. We arrived in Opua, NZ on November 9th after an exceptionally nice easy passage. Whew!

Christina met us at the dock in Opua (along with couple other good friends) and we spent some time cruising the Bay of Islands and the Tutukaka Coast in their company. (Let's just say that 8 people aboard is about all Shannon can comfortably handle!).

On November 29th, we hauled Shannon out of the water at Norsand Boatyard in Whangerei, NZ. There she'll sit in her cradle until we're ready to sail her again, which will probably end up being the spring of '12. Ken and Alina are back in Hawaii, and Christina and I are currently back in Montana for Christmas, enjoying some family time and all the good x-country skiing.

I hope to write an account of our experiences in Tonga and New Zealand before they fade from memory, so just because the Shannon isn't sailing anymore doesn't mean you shouldn't check the blog a few more times!

Christina and I will be heading back to Hawaii on Jan 13th to start work and replenish our severely depleated coffers!

Hope everyone had a great Holiday. Happy New Years!

No photos this time

10 October 2010

Kevin

Hey All, Having bad luck with this internet connection. Got about 6 photos uploaded to the Palmerston album, but that's all I can do. I'll get them up when I can.

Niue

10 October 2010 | Niue

Kevin

Niue. Let's see, where to begin.

Niue was an awesome place- very different from what we had previously experienced. As an ancient atoll that had been uplifted to a height of 200 feet, Niue is made of limestone and is as porous as a bathroom sponge. Due to this, the island is riddled with caves and chasms. From the ocean, the island looked like a long (9mi) pancake, very unappealing topographically, but as we got closer we could see incredible cliff formations along the coast, and a nicely developed fringing reef. We had just spent the last week or so getting hammered by 30-40kt winds on our run from Palmerston Island to Beveridge Reef and then Niue. We were always running with it, so the 15-20ft seas (sometimes breaking) were really no problem, and our windvane kept us tracking nicely. Just as we approached Niue, the conditions began to improve and we coasted around the southern tip into the lee of the island. As we neared the only major town, a yacht passed us and hailed us on the radio. Turns out it was the commodore of the Niue yacht club, and he offered to guide us to a mooring off the main wharf.. The yacht club is a small, somewhat ramshackle organization that houses its headquarters in the local ice cream parlor, and doesn't have a single yacht of its own. They are more like a social club that maintains facilities for cruisers (showers, book exchange, etc) and maintains the 15 or so moorings laid out for transient boats.

In 2004 hurricane Heta hit the island with 300km/hr winds and pretty much destroyed everything. 60% of the islands residents just up and left, apparently finding it far easier to relocate to New Zealand (of which Niue is a protectorate) than rebuild from the wreckage. 3 out of every 4 houses on the island lie abandoned and falling in, giving it a post-apocalyptic feel. That, combined with the custom of burying all loved ones in large concrete grave-bunkers in front yards, along the sides of the road, in clearings in the woods, and in front of public places (much as they do in Samoa) gave Niue an even more war-torn vibe. In addition to the wreckage on land, all the moorings were destroyed and so the yacht club has been re-installing them over the past couple of years. Now they are super nice, with all new anchors and hardware. We felt good tying Shannon up to one of them. I like the move toward permanent moorings in places where cruising sailboats frequent. They save a lot of coral damage (and it is a heck of a lot easier to pick up and release from a mooring than to haul in 200ft of 3/8" chain by hand ,like we do, when we set anchor).

The first thing we saw when arriving was a banded sea krait swimming in the water next to the mooring. As soon as it saw us, it gave a whip of its tail and dove for the bottom. These awesome creatures were everywhere in Niue, and with a venom purportedly 5x more toxic than a king cobra, were quite something to get used to. When freediving, these snakes would come right up to you, get right in your face or attempt to swim around your appendages. They were really cute, and being rear-fanged snakes with tiny mouths, would probably have a hard time getting venom into any part of you even if they wanted to. We heard reports of the boys on the island picking them up and throwing them at the little girls. Awesome. I wrote a post all about them on RTW. Even got a little video. Check it out if you like, it'll probably be posted in a week or two.

So, after we tied up to the mooring, we made the rounds to the neigboring boats and said hi to a few that we knew. We met a nice couple, Bruce and Alene, on a 40ft trimaran who gave us the lowdown on all the cool stuff to do on Niue, which basically consisted of lots of caving.

Whenever we get to a new island group or country, the first thing we have to do is check in with customs, health and immigration. Usually this means shouldering the pack with our bulging folder of passports and boat documents, and hiking around town until you find that one dusty old building that houses the various offices. Niue's customs office was located in the back of a building that looked like it had been a school, right in the heart of Alofi town (back when there were 3x more kids on the island, I'm sure it was a school). The woman inside welcomed us with a deadpan look that said "great, more yachties" and processed us through with automaton efficiency. Immigration was to be found in the back of the Police station, and was staffed by the most jovial woman. She was all smiles and was curious about who we were and where we had come from. Very nice. After taking care of business there,we set off to be proactive about finding a solution to our broken inverter. A man at the wharf had recommended that we go see a guy named Terry, who lived up the road out of town a ways. Ken, Britton, Alina and I set off along the road, walking past Captain Cook's landing place (where he was immediately run off by several Niueans painted up with red banana dye)and the dilapidated Niue Airlines office. Finally, we reached the abode of Terry, who seemed to live in amongst piles of all kinds of awesome rusting junk. Scooters, weedwhackers, transmissions, batteries, computers, chainsaws, sheet metal, shipping containers, piles of rusty springs, bolts, tires, etc. Terry was an older, slightly sweaty Kiwi expat who seemed to have a monopoly on the used appliance/motorized yard tool/computer repair market on Niue. As we shook hands, I notice that like all good mechanics, he was missing a digit or two. We described to him our predicament and he went immediately into one of his shipping containers and brought out what looked to be part of a computer. "Here" he said. "Wire this up to your battery (indicating two wires sprouting from a hand-poked hole in the side of the casing), and plug this in here (he scrounged for a powerstrip). It's just a power supply for a computer, rewired to be supplied by external batteries instead of the ones inside. It puts out 220 volts AC. I made up a couple of them to use with my wind generator battery bank up at my house. You can have it for free."

We stood there dumbfounded. Ok, awesome! Thanks Terry! We were expecting to have to drop at least $100 for any solution to our problem, if we could even find one.... Still a little skeptical however, we walked away with the new device in my backpack. It looked to be vintage 1991, and was only sightly smaller than a Cray supercomputer. Concerned as we were about whether it would actually work or not, we were actually more worried about finding enough space to put the thing, should it fulfill our needs.

Back in town, we walked around and cased the joint. This took us all of 5 minutes, and after we'd seen the Swanson's Limited Supermarket (definitely limited), the spartan bakery/pool hall combo, and a strange little hostel with built-in junk shop, we decided to call it a day and retired to the boat. A half hour after arrival, we had the new power inverter device wired up and it was pumping out 220 volts like a champ! We had to move out a stack of provisions to make room for it in the sliding compartment under the chart table, but once installed, we barely think about it anymore (that was a month ago). We brought Terry a bottle of wine a couple days later to say thanks...

Alofi town could only be described as comatose. Barely a pulse. The whole week we stayed there, we probably saw less than 100 souls, and half of those were at the yacht club potluck we attended one night. Aside from the people we met in shops or offices, the local people very much kept to the themselves, and it wasn't until we had rented a car and drove out into the interior did we start to see more people going about their daily lives (mostly farming taro in the rocky soil). Culturally, Niue seems to be in trouble. With far more Niueans living oversees than on Niue, the local population seems scattered, tired, disjointed, and a little sad. It was really too bad. We tried to track down the saturday market and the wednesday cultural practice, but couldn't seem to find either. Granted, I'm sure I don't know the whole story, but that is just the feeling I got.

So, with that we turned to full-time caving and exploring. First we rented a car, which at only $20US per day, was a steal split between the four of us. It was a tiny silver Mazda mini wagon, which we named Lord Kelvin, and it served us like no land rover could. Trying to get to some of these caves without a car would have been pretty hard. I'll just list off a description of some of the places we went..

Togo chasm:

This was pirates of the Carribean all the way. After hiking for about half and hour through the dense forest on the plateau of the island, we popped out near the edge of the cliff above the ocean. A huge ladder made out of telephone poles and 2x4s took us straight down through a slot in the rock into this amazing oasis at the bottom of the shaft. There were palm trees, ferns, moss, and sand dunes. There was also an extremely stagnant pool of cruddy water that Brit decided to taste to determine if it was salt or fresh. Why I do not know. An offshoot from the chasm led to the back end of a sea cave where you could stand on a rock while the huge breakers blasted in through the mouth and washed up all around.

Anapala Caves:

A short hike from the road led us to a crack in the rock, which after entering, led down down down at least 100 feet until you were left standing at the head of a freshwater pool at the bottom of an honest cravasse about 8ft wide(looking straight up, the sunlight was the thinnest crack). We donned our masks and fins and jumped into the pool. It was crystal clear fresh water (about 68degrees though, which was pretty cold)The pool was deep (40 feet maybe) and filled with awesome dribbling stalactite features and overhangs,etc. We dove down through an underwater opening and came up in another separate chamber. From there we climbed up a steep rockslide about halfway back up to daylight and entered another shaft (Brit and Ken did this while Alina and I stayed at the top). Vines assisted their decent into this cave where they discovered another set of deep deep pools in the bottom, filled with creepy roots and crawling vines.

Talava Arches:

These were some pretty impressive sea arches carved into the cliff along the northwest shore. We came early in the morning at low tide so we could hike around the base of the arches on the reef flat and make it around to Makalea caves further down the coast. Not only did we find Makalea caves, but we also discovered another set of caves further on that didn't seem to be named or marked on any map. (We were searching for a geocache along the coast which we never suceeded in finding) These caves were awesome chambers filled with stalactites, stalagmites, and fully formed columns. The awesome thing about Niue is the feeling you get that you are one of the first to experience the place. There are no signs to any of these caves, and once you get there, there are no ropes or barriers or anything to let you know that you are not the first person ever to have been there (ok, we did see the occasional name carved in the wall) But we were discussing what a similar geologic feature would be like back in the states. Not only would there be excessive signage warning of loose rocks, dangerous heights, deep water,idiot tourists, and potential lawsuits, but the cave itself would be roped off to the point where all the cave formations would be kept so far away that you couldn't really see them, despite the artificial lighting that would have undoubtedly been installed. Here in Niue, if you felt so inclined, you could waltz up and break off several hundred stalactites to take home as souveniers. It appears that no one feels so inclined. Isn't that nice?

Matapa Chasm:

Here, freshwater from the subterrainian aquifer pours out into a tidepool at the bottom of a 60ft chasm located just in from the ocean cliffs. The pool was great for swimming and cliff jumping and the mix of fresh on top and salt water below created a fuzzy shimmering mirage-like layer at the thermocline. Swimming along with mask and snorkel at the surface you couldn't see much, as if you just had your eyes open underwater, but as soon as you dove down a few feet, it all became clear.

Ulupaka Cave:

This one was a nice hike through the Niue Forest Reserve, among huge mahogany trees, banyans, rocky outcroppings and hundreds of spiderwebs inhabited by monstrous yellow arachnids. The person breaking trail had to wave a big stick in front of himself the whole time to avoid being plastered in the face with one of the very intricate 3D webs (that was me). To find the cave, we had to take an overgrown offshoot from the trail (which I think most people must miss) above a steep decent to the reef. Once at the cave, it is an easy scramble back into an inner chamber where there is a skylight and ferns growing amongst the stalagmites.. After investigating every nook and cranny of the chamber we found that this was not quite the end of the road. There was a small hole in the floor with a spiderweb across it that led down into blackness, giving us the distinct impression that we were standing on a gossamer ceiling above a deep chamber. Needless to say, we returned the next day with a rope, and Ken and I lowered ourselves down through the hole. After shinnying down 30 feet of free-swinging line and landing in a pile of animal bones, we looked around at our decidedly different surroundings. Instead of the usual limestone, the interior of this cave was made up entirely of huge slabs of loose sandstone, made up of millions of tiny little shells and coral particles. There were huge chunks and slabs of this stuff hanging off the ceiling, and erosion of the rock had created dunes on the floor of the cave. We saw no footprints on the dunes, which said to us that either no one had been down here in a long long time, or the sand was raining down off the ceiling at an alarming rate... The cave turned out to consist of three separate chambers, the final one containing a large freshwater pool with an island of sandstone in the middle. Hanging off the wall near the shore of the pool was the most gossamer stalactite I'd ever seen. It was about 3 feet long and only as big around as a pencil. It was hollow in the middle, just like a drinking straw, and its walls were paper thin.. After a quick exploration, Ken and I decided not to push our luck and tiptoed back to the opening, trying not to touch anything. We then hand-over-handed it back up the rope and back out the hole (myself somewhat less than gracefully).

Vaikona Cave:

This was the Niue motherlode of caving awesomeness. Our friends Bruce and Alene had drawn us a map of all the chambers they'd discovered in their exploration of the cave, so we had some kind of idea of what to expect. A good 45 minutes of hiking led us from the road to the cave entrance, which again was easy to miss and we had to battle our way through a tunnel-trail of dead pandanus leaves to the unassuming entrance. We felt a little like Team Zissou as we suited up in our wetsuits, booties, gloves, lights, cameras, and tucked our fins into our weightbelts, all the while standing in the woods. (All except for Brit, who has his own built-in wetsuit, the lucky #$%) We all slipped down into the crack in the rock and scuttled like crabs down some slippery sloping limestone to another crack, below which we could see a clear freshwater pool. With the aid of a rope someone had put there, we one by one made the Stallone-like move and stepped across the crack over the void. Once across, we made our way into a huge chamber with a wide open skylight 50 feet up. The floor of the chamber was a freshwater pool, crystal clear. We got in the pool, whooping like banshees at the frigid temperature. The pool ended at the far wall of the chamber, but by diving down about 10 feet, you could swim under the wall through a submerged tunnel, and up into another chamber, nearly pitch black. And so it went, each successive pool had an underwater swim-through leading to another chamber. Ken and I had the only two underwater lights, so one of us would scout the next dive, sometimes diving down only to discover that that particular tunnel was a dead-end and would have to turn around. We've all got pretty good breath holds, but when the water is cold and you're not exactly sure where the next air pocket will be, it's hard to keep your heart rate down. So, our bottom times were definitely less than desireable. Once we had found a connecting tunnel, we'd go back to Alina and Brit and stagger our dives so one lightless person would follow a light. The fourth chamber had us all coming up one right after another into a little air pocket, and we all crowded together to get enough room. I took a photo of us in there, and everybody's eyes are a little wide. There were some little fish in these freshwater pools- little cardinalfish looking guys who never see the light of day. Also, there were freshwater eels 2-3 feet long swimming around in there. If you've never seen a freshwater eel, they are probably the least intimidating of the eel family. They all look kind of dopey and lethargic like they should have names like Melvin or Hermy.

We knew from Bruce and Alene that there was a way out the other side of the cave system without having to retrace our steps, so despite the fact that everyone was very cold, we kept going. Due to a particular incident involving Britton, my light, and a moving rock, my light started to go on the fritz about halfway through the cave. It would randomly turn off without warning, but would usually come back on with a tap or two from the heel of my hand. Nice. After several more chambers, the roofs of which were very close to the surface of the water, and a scramble over some wedged boulders, we finally found ourselves with nowhere else to go but up. We had dead-ended in a large chamber with a high ceiling and a crack that led up about 70 feet to a dim hint of daylight. Ken and I had taken turns scouting down a particularly long submerged tunnel that extended further back, hopscotching tiny airpockets filled with tiny stalactites (a great way to brain yourself when coming up with a strong urge to breath..), but had discovered nothing but dead-ends. So, after returning to our somewhat hypothermic friends waiting for us in the high chamber, we began to climb up the crack. Sure enough, it led out a tiny hole into the daylight and onto the shelf above the ocean cliffs.

Hiking back to the cave entrance was more exercise in not getting sliced to ribbons than it was hiking. The surface of the ground in that particular spot is probably one of the only spots on earth that I could comfortably call "rugged". I really kinda hate that word. It always conjures images of L.L. Bean-clad yuppies posing on some rock outcropping in Maine, showing off their unscuffed hiking boots.

"Hey Jan, it sure is a good thing we bought all this expensive mountain gear."

"You're right Rick, this terrain sure is rugged"....

So, in all but the most deserving circumstances, I avoid use of that word. But here, trying to walk 50 feet over the ground had you doing at least 200 feet of up and down vertical climbing over what looked like piles of giant 10 foot limestone knives, dropped from the sky, and then aligned with a huge magnet to stand straight up, blade up. These knives were interspersed with wiry scrub bushes which did a good job concealing the many gaping holes and bottomless cracks that filled the area. You could either hop like an insane person from knife-tip to knifetip and hope to not slip and impale your nether-regions, or you could crawl like an old man on your hands and knees. Neither worked very well.

The cool thing about all these fantastic caves and chasms on Niue was that we never once saw another person at any of them. If any one of these caves existed on Oahu, there were be hundreds of people visiting them every day.

A few more days were spent in Niue freediving and checking out snakes and sea caves along the shore near the boat. The underwater visibility there was awesome. I read in one of our guidebooks that the complete lack of sediment runoff from the island (because it is so porous) makes for some of the best vis in the world, up to 250 feet sometimes. We didn't see much better than 150 feet, but it was still nice.

I ran into fellow NOAA co-worker Mike Musyl on the pier one night as I was launching our dinghy. He was in Niue tagging ono for some pelagic fish project. Small world.

We had a fairly interesting predicament while on Niue. None of us had much cash. The only bank on the island didn't have an ATM, and would only either exchange money or give you a cash advance on your credit card. The fees associated with that latter option were scary, especially since it was in international transaction, so we shied away from that. We each had a few bills of NZ money left over from Rarotonga... Thank god the car rental agency accepted credit card. It seemed to be the only business there that did. So, we were very frugal and pooled our remaining cash to keep eating. We bought a couple of loaves of bread, a few cans of tomatoes, and a jar of jam. We eyed a very tasty looking cucumber in the store, but after seeing the price tag of $10, we passed. We had jam sandwiches and oatmeal for at least two out of three meals a day. Departure tax (paid only in cash) was $35 per person, and mooring fees were $15/day. After putting aside enough for that and purchasing our bread, we had just enough to pay for a couple of $2 ice cream cones on our last day- our only splurging.

By the time our week in Niue was up, we were one of only two boats there.

Niue was an awesome place- very different from what we had previously experienced. As an ancient atoll that had been uplifted to a height of 200 feet, Niue is made of limestone and is as porous as a bathroom sponge. Due to this, the island is riddled with caves and chasms. From the ocean, the island looked like a long (9mi) pancake, very unappealing topographically, but as we got closer we could see incredible cliff formations along the coast, and a nicely developed fringing reef. We had just spent the last week or so getting hammered by 30-40kt winds on our run from Palmerston Island to Beveridge Reef and then Niue. We were always running with it, so the 15-20ft seas (sometimes breaking) were really no problem, and our windvane kept us tracking nicely. Just as we approached Niue, the conditions began to improve and we coasted around the southern tip into the lee of the island. As we neared the only major town, a yacht passed us and hailed us on the radio. Turns out it was the commodore of the Niue yacht club, and he offered to guide us to a mooring off the main wharf.. The yacht club is a small, somewhat ramshackle organization that houses its headquarters in the local ice cream parlor, and doesn't have a single yacht of its own. They are more like a social club that maintains facilities for cruisers (showers, book exchange, etc) and maintains the 15 or so moorings laid out for transient boats.

In 2004 hurricane Heta hit the island with 300km/hr winds and pretty much destroyed everything. 60% of the islands residents just up and left, apparently finding it far easier to relocate to New Zealand (of which Niue is a protectorate) than rebuild from the wreckage. 3 out of every 4 houses on the island lie abandoned and falling in, giving it a post-apocalyptic feel. That, combined with the custom of burying all loved ones in large concrete grave-bunkers in front yards, along the sides of the road, in clearings in the woods, and in front of public places (much as they do in Samoa) gave Niue an even more war-torn vibe. In addition to the wreckage on land, all the moorings were destroyed and so the yacht club has been re-installing them over the past couple of years. Now they are super nice, with all new anchors and hardware. We felt good tying Shannon up to one of them. I like the move toward permanent moorings in places where cruising sailboats frequent. They save a lot of coral damage (and it is a heck of a lot easier to pick up and release from a mooring than to haul in 200ft of 3/8" chain by hand ,like we do, when we set anchor).

The first thing we saw when arriving was a banded sea krait swimming in the water next to the mooring. As soon as it saw us, it gave a whip of its tail and dove for the bottom. These awesome creatures were everywhere in Niue, and with a venom purportedly 5x more toxic than a king cobra, were quite something to get used to. When freediving, these snakes would come right up to you, get right in your face or attempt to swim around your appendages. They were really cute, and being rear-fanged snakes with tiny mouths, would probably have a hard time getting venom into any part of you even if they wanted to. We heard reports of the boys on the island picking them up and throwing them at the little girls. Awesome. I wrote a post all about them on RTW. Even got a little video. Check it out if you like, it'll probably be posted in a week or two.

So, after we tied up to the mooring, we made the rounds to the neigboring boats and said hi to a few that we knew. We met a nice couple, Bruce and Alene, on a 40ft trimaran who gave us the lowdown on all the cool stuff to do on Niue, which basically consisted of lots of caving.

Whenever we get to a new island group or country, the first thing we have to do is check in with customs, health and immigration. Usually this means shouldering the pack with our bulging folder of passports and boat documents, and hiking around town until you find that one dusty old building that houses the various offices. Niue's customs office was located in the back of a building that looked like it had been a school, right in the heart of Alofi town (back when there were 3x more kids on the island, I'm sure it was a school). The woman inside welcomed us with a deadpan look that said "great, more yachties" and processed us through with automaton efficiency. Immigration was to be found in the back of the Police station, and was staffed by the most jovial woman. She was all smiles and was curious about who we were and where we had come from. Very nice. After taking care of business there,we set off to be proactive about finding a solution to our broken inverter. A man at the wharf had recommended that we go see a guy named Terry, who lived up the road out of town a ways. Ken, Britton, Alina and I set off along the road, walking past Captain Cook's landing place (where he was immediately run off by several Niueans painted up with red banana dye)and the dilapidated Niue Airlines office. Finally, we reached the abode of Terry, who seemed to live in amongst piles of all kinds of awesome rusting junk. Scooters, weedwhackers, transmissions, batteries, computers, chainsaws, sheet metal, shipping containers, piles of rusty springs, bolts, tires, etc. Terry was an older, slightly sweaty Kiwi expat who seemed to have a monopoly on the used appliance/motorized yard tool/computer repair market on Niue. As we shook hands, I notice that like all good mechanics, he was missing a digit or two. We described to him our predicament and he went immediately into one of his shipping containers and brought out what looked to be part of a computer. "Here" he said. "Wire this up to your battery (indicating two wires sprouting from a hand-poked hole in the side of the casing), and plug this in here (he scrounged for a powerstrip). It's just a power supply for a computer, rewired to be supplied by external batteries instead of the ones inside. It puts out 220 volts AC. I made up a couple of them to use with my wind generator battery bank up at my house. You can have it for free."

We stood there dumbfounded. Ok, awesome! Thanks Terry! We were expecting to have to drop at least $100 for any solution to our problem, if we could even find one.... Still a little skeptical however, we walked away with the new device in my backpack. It looked to be vintage 1991, and was only sightly smaller than a Cray supercomputer. Concerned as we were about whether it would actually work or not, we were actually more worried about finding enough space to put the thing, should it fulfill our needs.

Back in town, we walked around and cased the joint. This took us all of 5 minutes, and after we'd seen the Swanson's Limited Supermarket (definitely limited), the spartan bakery/pool hall combo, and a strange little hostel with built-in junk shop, we decided to call it a day and retired to the boat. A half hour after arrival, we had the new power inverter device wired up and it was pumping out 220 volts like a champ! We had to move out a stack of provisions to make room for it in the sliding compartment under the chart table, but once installed, we barely think about it anymore (that was a month ago). We brought Terry a bottle of wine a couple days later to say thanks...

Alofi town could only be described as comatose. Barely a pulse. The whole week we stayed there, we probably saw less than 100 souls, and half of those were at the yacht club potluck we attended one night. Aside from the people we met in shops or offices, the local people very much kept to the themselves, and it wasn't until we had rented a car and drove out into the interior did we start to see more people going about their daily lives (mostly farming taro in the rocky soil). Culturally, Niue seems to be in trouble. With far more Niueans living oversees than on Niue, the local population seems scattered, tired, disjointed, and a little sad. It was really too bad. We tried to track down the saturday market and the wednesday cultural practice, but couldn't seem to find either. Granted, I'm sure I don't know the whole story, but that is just the feeling I got.

So, with that we turned to full-time caving and exploring. First we rented a car, which at only $20US per day, was a steal split between the four of us. It was a tiny silver Mazda mini wagon, which we named Lord Kelvin, and it served us like no land rover could. Trying to get to some of these caves without a car would have been pretty hard. I'll just list off a description of some of the places we went..

Togo chasm:

This was pirates of the Carribean all the way. After hiking for about half and hour through the dense forest on the plateau of the island, we popped out near the edge of the cliff above the ocean. A huge ladder made out of telephone poles and 2x4s took us straight down through a slot in the rock into this amazing oasis at the bottom of the shaft. There were palm trees, ferns, moss, and sand dunes. There was also an extremely stagnant pool of cruddy water that Brit decided to taste to determine if it was salt or fresh. Why I do not know. An offshoot from the chasm led to the back end of a sea cave where you could stand on a rock while the huge breakers blasted in through the mouth and washed up all around.

Anapala Caves:

A short hike from the road led us to a crack in the rock, which after entering, led down down down at least 100 feet until you were left standing at the head of a freshwater pool at the bottom of an honest cravasse about 8ft wide(looking straight up, the sunlight was the thinnest crack). We donned our masks and fins and jumped into the pool. It was crystal clear fresh water (about 68degrees though, which was pretty cold)The pool was deep (40 feet maybe) and filled with awesome dribbling stalactite features and overhangs,etc. We dove down through an underwater opening and came up in another separate chamber. From there we climbed up a steep rockslide about halfway back up to daylight and entered another shaft (Brit and Ken did this while Alina and I stayed at the top). Vines assisted their decent into this cave where they discovered another set of deep deep pools in the bottom, filled with creepy roots and crawling vines.

Talava Arches:

These were some pretty impressive sea arches carved into the cliff along the northwest shore. We came early in the morning at low tide so we could hike around the base of the arches on the reef flat and make it around to Makalea caves further down the coast. Not only did we find Makalea caves, but we also discovered another set of caves further on that didn't seem to be named or marked on any map. (We were searching for a geocache along the coast which we never suceeded in finding) These caves were awesome chambers filled with stalactites, stalagmites, and fully formed columns. The awesome thing about Niue is the feeling you get that you are one of the first to experience the place. There are no signs to any of these caves, and once you get there, there are no ropes or barriers or anything to let you know that you are not the first person ever to have been there (ok, we did see the occasional name carved in the wall) But we were discussing what a similar geologic feature would be like back in the states. Not only would there be excessive signage warning of loose rocks, dangerous heights, deep water,idiot tourists, and potential lawsuits, but the cave itself would be roped off to the point where all the cave formations would be kept so far away that you couldn't really see them, despite the artificial lighting that would have undoubtedly been installed. Here in Niue, if you felt so inclined, you could waltz up and break off several hundred stalactites to take home as souveniers. It appears that no one feels so inclined. Isn't that nice?

Matapa Chasm:

Here, freshwater from the subterrainian aquifer pours out into a tidepool at the bottom of a 60ft chasm located just in from the ocean cliffs. The pool was great for swimming and cliff jumping and the mix of fresh on top and salt water below created a fuzzy shimmering mirage-like layer at the thermocline. Swimming along with mask and snorkel at the surface you couldn't see much, as if you just had your eyes open underwater, but as soon as you dove down a few feet, it all became clear.

Ulupaka Cave:

This one was a nice hike through the Niue Forest Reserve, among huge mahogany trees, banyans, rocky outcroppings and hundreds of spiderwebs inhabited by monstrous yellow arachnids. The person breaking trail had to wave a big stick in front of himself the whole time to avoid being plastered in the face with one of the very intricate 3D webs (that was me). To find the cave, we had to take an overgrown offshoot from the trail (which I think most people must miss) above a steep decent to the reef. Once at the cave, it is an easy scramble back into an inner chamber where there is a skylight and ferns growing amongst the stalagmites.. After investigating every nook and cranny of the chamber we found that this was not quite the end of the road. There was a small hole in the floor with a spiderweb across it that led down into blackness, giving us the distinct impression that we were standing on a gossamer ceiling above a deep chamber. Needless to say, we returned the next day with a rope, and Ken and I lowered ourselves down through the hole. After shinnying down 30 feet of free-swinging line and landing in a pile of animal bones, we looked around at our decidedly different surroundings. Instead of the usual limestone, the interior of this cave was made up entirely of huge slabs of loose sandstone, made up of millions of tiny little shells and coral particles. There were huge chunks and slabs of this stuff hanging off the ceiling, and erosion of the rock had created dunes on the floor of the cave. We saw no footprints on the dunes, which said to us that either no one had been down here in a long long time, or the sand was raining down off the ceiling at an alarming rate... The cave turned out to consist of three separate chambers, the final one containing a large freshwater pool with an island of sandstone in the middle. Hanging off the wall near the shore of the pool was the most gossamer stalactite I'd ever seen. It was about 3 feet long and only as big around as a pencil. It was hollow in the middle, just like a drinking straw, and its walls were paper thin.. After a quick exploration, Ken and I decided not to push our luck and tiptoed back to the opening, trying not to touch anything. We then hand-over-handed it back up the rope and back out the hole (myself somewhat less than gracefully).

Vaikona Cave:

This was the Niue motherlode of caving awesomeness. Our friends Bruce and Alene had drawn us a map of all the chambers they'd discovered in their exploration of the cave, so we had some kind of idea of what to expect. A good 45 minutes of hiking led us from the road to the cave entrance, which again was easy to miss and we had to battle our way through a tunnel-trail of dead pandanus leaves to the unassuming entrance. We felt a little like Team Zissou as we suited up in our wetsuits, booties, gloves, lights, cameras, and tucked our fins into our weightbelts, all the while standing in the woods. (All except for Brit, who has his own built-in wetsuit, the lucky #$%) We all slipped down into the crack in the rock and scuttled like crabs down some slippery sloping limestone to another crack, below which we could see a clear freshwater pool. With the aid of a rope someone had put there, we one by one made the Stallone-like move and stepped across the crack over the void. Once across, we made our way into a huge chamber with a wide open skylight 50 feet up. The floor of the chamber was a freshwater pool, crystal clear. We got in the pool, whooping like banshees at the frigid temperature. The pool ended at the far wall of the chamber, but by diving down about 10 feet, you could swim under the wall through a submerged tunnel, and up into another chamber, nearly pitch black. And so it went, each successive pool had an underwater swim-through leading to another chamber. Ken and I had the only two underwater lights, so one of us would scout the next dive, sometimes diving down only to discover that that particular tunnel was a dead-end and would have to turn around. We've all got pretty good breath holds, but when the water is cold and you're not exactly sure where the next air pocket will be, it's hard to keep your heart rate down. So, our bottom times were definitely less than desireable. Once we had found a connecting tunnel, we'd go back to Alina and Brit and stagger our dives so one lightless person would follow a light. The fourth chamber had us all coming up one right after another into a little air pocket, and we all crowded together to get enough room. I took a photo of us in there, and everybody's eyes are a little wide. There were some little fish in these freshwater pools- little cardinalfish looking guys who never see the light of day. Also, there were freshwater eels 2-3 feet long swimming around in there. If you've never seen a freshwater eel, they are probably the least intimidating of the eel family. They all look kind of dopey and lethargic like they should have names like Melvin or Hermy.

We knew from Bruce and Alene that there was a way out the other side of the cave system without having to retrace our steps, so despite the fact that everyone was very cold, we kept going. Due to a particular incident involving Britton, my light, and a moving rock, my light started to go on the fritz about halfway through the cave. It would randomly turn off without warning, but would usually come back on with a tap or two from the heel of my hand. Nice. After several more chambers, the roofs of which were very close to the surface of the water, and a scramble over some wedged boulders, we finally found ourselves with nowhere else to go but up. We had dead-ended in a large chamber with a high ceiling and a crack that led up about 70 feet to a dim hint of daylight. Ken and I had taken turns scouting down a particularly long submerged tunnel that extended further back, hopscotching tiny airpockets filled with tiny stalactites (a great way to brain yourself when coming up with a strong urge to breath..), but had discovered nothing but dead-ends. So, after returning to our somewhat hypothermic friends waiting for us in the high chamber, we began to climb up the crack. Sure enough, it led out a tiny hole into the daylight and onto the shelf above the ocean cliffs.

Hiking back to the cave entrance was more exercise in not getting sliced to ribbons than it was hiking. The surface of the ground in that particular spot is probably one of the only spots on earth that I could comfortably call "rugged". I really kinda hate that word. It always conjures images of L.L. Bean-clad yuppies posing on some rock outcropping in Maine, showing off their unscuffed hiking boots.

"Hey Jan, it sure is a good thing we bought all this expensive mountain gear."

"You're right Rick, this terrain sure is rugged"....

So, in all but the most deserving circumstances, I avoid use of that word. But here, trying to walk 50 feet over the ground had you doing at least 200 feet of up and down vertical climbing over what looked like piles of giant 10 foot limestone knives, dropped from the sky, and then aligned with a huge magnet to stand straight up, blade up. These knives were interspersed with wiry scrub bushes which did a good job concealing the many gaping holes and bottomless cracks that filled the area. You could either hop like an insane person from knife-tip to knifetip and hope to not slip and impale your nether-regions, or you could crawl like an old man on your hands and knees. Neither worked very well.

The cool thing about all these fantastic caves and chasms on Niue was that we never once saw another person at any of them. If any one of these caves existed on Oahu, there were be hundreds of people visiting them every day.

A few more days were spent in Niue freediving and checking out snakes and sea caves along the shore near the boat. The underwater visibility there was awesome. I read in one of our guidebooks that the complete lack of sediment runoff from the island (because it is so porous) makes for some of the best vis in the world, up to 250 feet sometimes. We didn't see much better than 150 feet, but it was still nice.

I ran into fellow NOAA co-worker Mike Musyl on the pier one night as I was launching our dinghy. He was in Niue tagging ono for some pelagic fish project. Small world.

We had a fairly interesting predicament while on Niue. None of us had much cash. The only bank on the island didn't have an ATM, and would only either exchange money or give you a cash advance on your credit card. The fees associated with that latter option were scary, especially since it was in international transaction, so we shied away from that. We each had a few bills of NZ money left over from Rarotonga... Thank god the car rental agency accepted credit card. It seemed to be the only business there that did. So, we were very frugal and pooled our remaining cash to keep eating. We bought a couple of loaves of bread, a few cans of tomatoes, and a jar of jam. We eyed a very tasty looking cucumber in the store, but after seeing the price tag of $10, we passed. We had jam sandwiches and oatmeal for at least two out of three meals a day. Departure tax (paid only in cash) was $35 per person, and mooring fees were $15/day. After putting aside enough for that and purchasing our bread, we had just enough to pay for a couple of $2 ice cream cones on our last day- our only splurging.

By the time our week in Niue was up, we were one of only two boats there.

Beveridge Reef

10 October 2010 | Nowhereland

Kevin

Beveridge Reef

After leaving Palmerston, we set a course for Beveridge Reef, 230 miles to the southwest. The frontal system that had kept winds above 30 knots for most of the previous week was not going anywhere, so we poled out about 50% of the genoa and flew downwind. We had heard about Beveridge Reef from a couple of other cruisers back in Papeete who recommended it as an awesome place to stop over between the Cooks and Niue. I looked for it on our electronic charts, but all it showed was a big green blotch (the color of dry reef) and made some vague comment as to the inaccuracy of the location and soundings. Before leaving Rarotonga, I had downloaded a hand-drawn chart of the reef itself from the internet. This chart at least showed the horseshoe shape of the reef, the pass on the western side, and the lagoon. But, strangely enough, the coordinates on the hand-drawn chart were close to a mile off the coordinates on our E-charts. We had expected this, as often remote reefs and islands like this are relying on bathymetric surveys from the 1800's (I kid you not, some of our paper charts for the Marquesas were from an 1882 survey). So, we just knew we'd have to find the reef the old fashioned way- arrive in the vicinity during daylight hours, and just watch like a hawk for the darned thing so we wouldn't run into it. We tend to do this anyway, even with well-charted places. The captain who ends up on the rocks is the one who trusts everything to his charts or any single source of information.

So, we planned our passage to arrive in the vicinity of Beveridge the morning of the third day at sea. When that morning arrived, and we neared the supposed location, we just kept watch for any sign of breakers, discolored clouds (green above the lagoon) or whatever. Sure enough, we saw breakers ahead, and as we rounded the southern side of the reef, plotted the actual position of the reef to be nearly 2 miles away from either of our charted locations. Go figure. Imagine trying to sail past the thing in the middle of the night, thinking you're giving it a two mile leeway, when BAM! It has definitely happened, as the fairly recent wreck of a longline fishing boat on the eastern side of the reef can attest to. When we entered the lagoon and swung up into the wind, we were blasted in the face by the force of the wind we'd been running with the whole time. It made us glad we hadn't been trying to beat into it! There were no other boats there. We motored dead upwind across the lagoon about a mile to the eastern side, and anchored a quarter mile from the wreck just off the edge of the sand margin in about 30 feet of water. This was where it transitioned from 6ft reef flat depths to the deeper (30ft) lagoon. We dropped the hook in 8 feet, with Shannon's keel just above the bottom, then drifted back over deeper water. Even the short fetch between the reef and the boat was kicking up pretty significant chop that occasionally found its way on deck. As it was, all the chop was right on the nose, so it was comfortable enough down below. The place is called Beveridge Reef, and even though it is not spelled quite the same, warranted a round of beverages for the crew. We sat up on deck in the brilliant sunshine and blasting wind and took a self-timed picture of the four of us on the bow with our beverages. It was so windy the camera kept blowing over.

We felt it was a little unsafe to go anywhere in the dinghy due to the high winds and our puny and occasionally less-than-reliable outboard (if it died, we'd be blown all the way across the lagoon and probably out the other side very quickly). So, we decided to take our exercise, and swim over to the longline wreck. When I jumped in the water I realized the incredibly good visibility of the place. With no land to cause sediment runoff, the water was super clear, despite the wind. On our way to the wreck we saw lots of stingrays, and a strange migration of thousands of nudibranchs, all crawling along in huge trains to no obvious destination.. The wreck was , well, a wreck, with the usual broken dishes, soggy matresses, empty engine room, and huge scar in the reef. We played around on it for a while, watching all the blacktip reef sharks swim around it in the shallow water with their dorsal fins out of the water . There was a whole school of Parrotfish lounging in a shallow spot next to the wreck, availing themselves of a thin stream of cool water coming in over the reef from the rising tide. Their tails and dorsal fins were out of the water too- something I'd never seen parrotfish do.

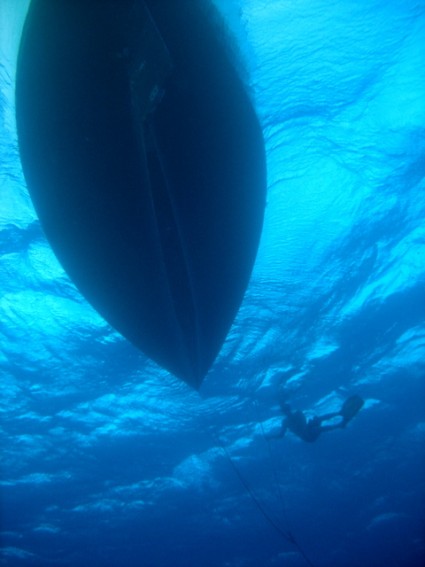

When we returned to the boat, I couldn't help but take advantage of the awesome visibility to take some photos of Shannon from below.

Because of the conditions, we decided we had seen most of what we could, and departed the next morning. Just prior to our departure, I realized that our power inverter had crapped out on us. Yes, the new one we had bought so recently in Tahiti. Well, it just refused to work, and so did our old one. What that means is that there's no way to charge the computer to run our chartplotting program. Ok, I thought, We'll just turn on the computer from time to time and do spot-checks of our position, and if we do that, the laptop battery should be able to last a few days, long enough to get the 130 miles to Niue. Well, the computer battery was stone cold dead. Hmmm. So, we broke out the backup computer. Its battery was also stone cold dead. A secret smile spread across my face as I realized that yes, technology had failed us and we would have to revert back to more traditional methods. So, we poured through our rolls of paper charts, looking for a chart of the vicinity. Well, I can tell you we have just about every other corner of the entire pacific covered, but not the no-man's land between the Cook Islands and Niue. I found one chart that covered the larger western pacific, but the exact area we needed to consult was covered by a map legend. Ha! So, with no other options, we consulted our sailing directions to at least assure there were no other uncharted reefs in our path to Niue, and busted out the plotting sheets to hand-draw our own chart. So, off we set thus, recording DR positions every hour in the log, and plotting our position from the backup handheld gps every so often. All the while I was secretly hoping that the backup gps would fail, requiring the sextant to be broken out and a noonsite to be taken the next day. Alas, it was not to be so, and we sailed into Niue a day and a half later under GPS and jury-rigged chart.

After leaving Palmerston, we set a course for Beveridge Reef, 230 miles to the southwest. The frontal system that had kept winds above 30 knots for most of the previous week was not going anywhere, so we poled out about 50% of the genoa and flew downwind. We had heard about Beveridge Reef from a couple of other cruisers back in Papeete who recommended it as an awesome place to stop over between the Cooks and Niue. I looked for it on our electronic charts, but all it showed was a big green blotch (the color of dry reef) and made some vague comment as to the inaccuracy of the location and soundings. Before leaving Rarotonga, I had downloaded a hand-drawn chart of the reef itself from the internet. This chart at least showed the horseshoe shape of the reef, the pass on the western side, and the lagoon. But, strangely enough, the coordinates on the hand-drawn chart were close to a mile off the coordinates on our E-charts. We had expected this, as often remote reefs and islands like this are relying on bathymetric surveys from the 1800's (I kid you not, some of our paper charts for the Marquesas were from an 1882 survey). So, we just knew we'd have to find the reef the old fashioned way- arrive in the vicinity during daylight hours, and just watch like a hawk for the darned thing so we wouldn't run into it. We tend to do this anyway, even with well-charted places. The captain who ends up on the rocks is the one who trusts everything to his charts or any single source of information.

So, we planned our passage to arrive in the vicinity of Beveridge the morning of the third day at sea. When that morning arrived, and we neared the supposed location, we just kept watch for any sign of breakers, discolored clouds (green above the lagoon) or whatever. Sure enough, we saw breakers ahead, and as we rounded the southern side of the reef, plotted the actual position of the reef to be nearly 2 miles away from either of our charted locations. Go figure. Imagine trying to sail past the thing in the middle of the night, thinking you're giving it a two mile leeway, when BAM! It has definitely happened, as the fairly recent wreck of a longline fishing boat on the eastern side of the reef can attest to. When we entered the lagoon and swung up into the wind, we were blasted in the face by the force of the wind we'd been running with the whole time. It made us glad we hadn't been trying to beat into it! There were no other boats there. We motored dead upwind across the lagoon about a mile to the eastern side, and anchored a quarter mile from the wreck just off the edge of the sand margin in about 30 feet of water. This was where it transitioned from 6ft reef flat depths to the deeper (30ft) lagoon. We dropped the hook in 8 feet, with Shannon's keel just above the bottom, then drifted back over deeper water. Even the short fetch between the reef and the boat was kicking up pretty significant chop that occasionally found its way on deck. As it was, all the chop was right on the nose, so it was comfortable enough down below. The place is called Beveridge Reef, and even though it is not spelled quite the same, warranted a round of beverages for the crew. We sat up on deck in the brilliant sunshine and blasting wind and took a self-timed picture of the four of us on the bow with our beverages. It was so windy the camera kept blowing over.

We felt it was a little unsafe to go anywhere in the dinghy due to the high winds and our puny and occasionally less-than-reliable outboard (if it died, we'd be blown all the way across the lagoon and probably out the other side very quickly). So, we decided to take our exercise, and swim over to the longline wreck. When I jumped in the water I realized the incredibly good visibility of the place. With no land to cause sediment runoff, the water was super clear, despite the wind. On our way to the wreck we saw lots of stingrays, and a strange migration of thousands of nudibranchs, all crawling along in huge trains to no obvious destination.. The wreck was , well, a wreck, with the usual broken dishes, soggy matresses, empty engine room, and huge scar in the reef. We played around on it for a while, watching all the blacktip reef sharks swim around it in the shallow water with their dorsal fins out of the water . There was a whole school of Parrotfish lounging in a shallow spot next to the wreck, availing themselves of a thin stream of cool water coming in over the reef from the rising tide. Their tails and dorsal fins were out of the water too- something I'd never seen parrotfish do.

When we returned to the boat, I couldn't help but take advantage of the awesome visibility to take some photos of Shannon from below.

Because of the conditions, we decided we had seen most of what we could, and departed the next morning. Just prior to our departure, I realized that our power inverter had crapped out on us. Yes, the new one we had bought so recently in Tahiti. Well, it just refused to work, and so did our old one. What that means is that there's no way to charge the computer to run our chartplotting program. Ok, I thought, We'll just turn on the computer from time to time and do spot-checks of our position, and if we do that, the laptop battery should be able to last a few days, long enough to get the 130 miles to Niue. Well, the computer battery was stone cold dead. Hmmm. So, we broke out the backup computer. Its battery was also stone cold dead. A secret smile spread across my face as I realized that yes, technology had failed us and we would have to revert back to more traditional methods. So, we poured through our rolls of paper charts, looking for a chart of the vicinity. Well, I can tell you we have just about every other corner of the entire pacific covered, but not the no-man's land between the Cook Islands and Niue. I found one chart that covered the larger western pacific, but the exact area we needed to consult was covered by a map legend. Ha! So, with no other options, we consulted our sailing directions to at least assure there were no other uncharted reefs in our path to Niue, and busted out the plotting sheets to hand-draw our own chart. So, off we set thus, recording DR positions every hour in the log, and plotting our position from the backup handheld gps every so often. All the while I was secretly hoping that the backup gps would fail, requiring the sextant to be broken out and a noonsite to be taken the next day. Alas, it was not to be so, and we sailed into Niue a day and a half later under GPS and jury-rigged chart.

Palmerston Atoll

10 October 2010 | Cook Islands

Kevin

Hey All, currently sitting in a nice little cafe in the town of Lifuka in the Ha'apai group of Tonga. Got a good internet connection here! I fininshed catching up on my chronicles of the past month or so, so here you are!

Palmerston

A small atoll on the western extremity of the southern group of the Cook Islands. Inhabited by a single extended family, they are somewhat sovereign, but still fall within the jurisdiction of the Cooks.

I've written so much about this place for Reach the World and in my own handwritten journal, that I just can't re-write it all again in utmost detail here without banging my head against a wall. Instead, I'll just transcribe my journal. Apologies for choppy sentences and poor flow!

9/7/10

Palmerston. Arrived at 10am after sandbagging at 2 knots all night to avoid arriving in the dark. Still blowing 30 knots. A sight greeted us as we rounded up onto the western side of the atoll: 10 other sailboats and the tall ship Picton Castle. Didn't expect much other vessel traffic at all. Can't get away from it! We were immediately intercepted by a local man in an aluminum skiff who raced out through the pass to meet us. He said "my name is Edward and I will be your host. I'll try to find you a mooring. This boat needs to leave" and he motioned to one of the boats to the south and sped off. Ken was at the helm and we motored up towards the tall ship Picton Castle, and impressive white three masted barque. We were gawked at from the rail by what looked to be the whole crew. Edward returned and said we'd have to drop anchor as the boat on the mooring was not leaving. He guided us to a good spot and indicated where to drop the hook. We set the hook, but we drifted back too close to a neighboring boat so we re-set. Edward motored back to the island to go get customs for us. Soon he returned with two other local guys Terry and Simon who were more than nice. Even though there are only 60 people on the island, these guys took their jobs seriously and wore uniforms etc. They took some tea and chatted amiably while filling out the paperwork. After they left, we listened to some Cat Stevens (first music in a week due to battery charging issues). Edward returned to pick us up to go ashore. He expertly guided us, and a couple of other cruisers (a castaway looking father and his two daughters) through the tiny pass at low tide, almost scraping bottom. Earlier we had dinghied out our second anchor for better holding in this steep-to anchorage. Edward led us ashore to his house, which was very open air. Main living area was poles with sheet metal roof, no walls. Kitchen looked like a chicken coop across the sand yard. Met Edward's mother, who was a sweet chatty old lady 80 years old who sat under the tin roof in an old ratty chair with ratty footstool and said "I don't walk too good anymore" and showed me her swollen legs and an old scar from a broken bone. Strangely, she was still able to easily touch her toes and massage her own feet. She told me the story of how one of her grandchildren had been born on the island in less than ideal circumstances and how she had been the mid-wife. I understood about 50% of the words she was saying, but followed along fairly well.

Edward's 15 year old son Davie soon took us on a walking tour of the small island, strutting ahead like he wanted to get it over with. Showed us the school, the packed sand tennis court, the original house built in 1862 by William Marsters of massive timbers from shipwrecks (still there but looks like a sponge from all the termite damage).. William Marsters (an Englishman) was the first colonizer of the island when in 1862 he settled here with three local wives from Penrhyn Island (one of the other Cook Islands). He then distributed the wives among three of the motus and made strict rules about interbreeding. What those were I cannot imagine, because nowadays, every single person on the island has the same last name: Marsters.

Davie also showed us the generator for island power, which runs for 6 hours a day, the admin offices (where we paid our $5NZ each for clearance), and back to the house. There are massive mahogany trees growing on the island, much to our surprise. Davie wants to be a policeman and is actually already training for the job (rarotonga). He asked if I skateboarded (probably a novelty for somebody from a place with no pavement) and if we surfed. No surf on Palmerston. The one guy who tried was apparently a professional surfer and ended up breaking his leg and having to be rescued.

Around 4:00, we all gathered at the village gathering area for a barbeque and performance from the crew of the tall ship. All crew were young (teens and early 20's)mostly americans and were covered with big polynesian tatoos, mostly across their chests...eeeesh. All of them got them in Rarotonga from the same guy. They're going to love those in about 10 years. The Picton Castle is here to deliver some cargo (picked up in Rarotonga) and to take some passengers up to Puka Puka from here. They are on their way around the world. Each crew member pays $40K to do the 14 month trip. The last supply ship to come to Palmerston was 6 months ago, so they probably needed it. While we waited for the performance, we mingled with the crew and a multitude of locals. I talked for some time with Goodly, Edward's brother. He told me about everything and graciously answered my question about sewage disposal and septic tanks on the island. The told me the story of how he, twice, had outboard motor problems while out fishing with no radio and only narrowly escaped drifting out to sea forever.. (he set his sea anchor etc, then figured out if you pull out the kill switch all the way and hold it there, the motor would run) I don't know why these guys don't save up for kickers.

The dancing by the male crew was pretty terrible. They had worked with one of the villagers to come up with a haka routine to a local song, and they went all out with palm leaf skirts etc. The women crew were a little better, and a couple of them had really mastered the Tahitian hip shake. All in all a valiant effort, but one that left us on the Shannon chuckling for many days after. The villagers from Puka Puka also put on a little show to say thanks for the hospitality of the Palmerston Islanders.. They sang some great songs in that awesome three part polynesian harmony the just gets me to my bones.

Feast! Every villager brought food and so did the crew of the Picton Castle. Breadfruit, beef, fish, chicken, pancakes with buttercream, rolls, breads, coconut dishes, oh my. I stuffed and stuffed, with an eye over my shoulder as squall after squall rolled in and the boats swung around a bit on their scope. Wind from the west would have had us up on the reef, the way the bottom is..

As it was getting dark, Edward loaded us up again in his boat and delivered us back to the Shannon, promising to come for us again in the morning. Standing outside to take a pee just now, I noticed the whitecaps stirring up the bioluminescence....

and recalled that at the BBQ I had been solicited casually for my, ahem, "genetic contribution", by the friend of the reverend's wife. Those strict rules on interbreeding, I guess.

9/8/10

Picton Castle had an open-house. Edward picked us up around 11 and ferried us over to the ship where we climbed aboard via rope ladder and were immediately taken on a tour by Tammy, a trainee aboard from Canada. She wasn't cleared to go aloft just yet, but stuck to furling headsails on the bowsprit. The whole village was also there, checking out the ship. The steward made tons of food for everyone and laid it out on deck amidships on the cargo hatch. Brit, who always gets roped into rough-housing with local kids, in an effort to hoist a little girl up in the air, bonked her head against the overhang of the coachroof. I had to laugh. A group of people from Puka Puka are catching a ride home on the tallship due to the infrequency of cargo ships heading there. It kinda feels like we're back in time a century or two- a sailing ship delivering cargo and passengers to remote islands.. pretty cool. One nice lady from Puka Puka was sitting along the bulwark off to one side with a plastic bag full of skinned cooked seabirds (tropicbirds). Later we saw a derelict carcass on the seat of one of the small boats. Once again, I had to laugh.

There was a little local kid with long flowing black curly locks who was getting waaaaay too much attention from the crew of the ship and everybody else. He was pretending all the food was his, hitting people (he slapped me in the face when I tried to take a handful of popcorn), stealing hats and riding on people's shoulders...

Once the tours were over, the cruisers and locals gathered on the main deck by the cargo hold. Locals gathered on the starboard side, and cruisers gathered on the port side, with very little mingling. I tried to break the mold, but only succeeded in talking to a few locals and generally looking lonely and slightly creepy. Eventually, I met all the other cruisers: Graham and Julie, Alex and Amelia on "Artimo". Big Texas and wife Jules on "Simpatica" and Lisa and John (heli-ski guide) and kids on "Tyee".

The captain of the Picton Castle was a soggy fleshy looking man with droopy-dog eyes, who still managed to somehow look like a famous movie star, and was just as charismatic. He gave a speech, and all gathered (probably 100 people)to hear.. Something cheezy about hospitality and emotional generosity, then the reverend spoke, and then the mayor Bill. Then, once again, the crew of the Picton castle performed their dance again, utterly unimproved from the day before. The guy's routine went as follows:

Villagers on ukuleles and guitars sang this song:

"Welcome to Picton Castle,

Hello, kia orana to you,

I assuuuuuuume this is whaaaat

You want to seeeeeee!"

While the dancers did the haka and motioned to their crotchal regions on the last line..

After the crew dance, four local Marsters got up and did a nice dance to a more wholesome song, with a last line of

"You'll never find another Marsters girl like me..."

At least they can poke fun at their own strange geneology!

At the conclusion of the performance, Big Texas shouted "All ashore thats going ashore!" and was immediately reprimanded by the captain: "I did NOT say that"...

One of the PC crew was only 17 and had seen the Picton Castle on TV when she was 9 years old, and had been saving ever since to come aboard for a voyage. She was Irish. She must have had one heck of an allowance to affort the $40K ticket.

After about 3 hours aboard, Edward dropped us back off at the Shannon. We watched as the Picton Castle got underway. The entire crew gathered on the focsle and took turns pumping up and down on the huge manual windlass. As the ship crept towards her anchor, several of the square sails were unfurled. When she finally broke free of the bottom, she stood off to the north and picked up speed as more and more sail was put on her. It was like watching pure poetry. Now, a quiet evening aboard while the winds continue to rage outside.

9/9/10

During the night, one of the other yachts, "Calypso" broke free of their mooring and drifted out to sea. In the morning we heard talk on the radio of plans to set down a new mooring. So when Edward came to pick us up, Ken and I jumped in the boat with our dive gear (me with scuba stuff too) and went to the spot where we searched for the old chain to no avial. Must've ripped the whole thing out. Canadians Lucy and John showed up with more scuba gear and got in the water with us. Found a good spot for new chain and did it up through a nice big puka in the reef. John dropped his pliers and they shot off down the reef slope like a spaceship. I never saw anything so cool. Luckily I kept my eye on the place where they landed and was able to retrieve them. Eddie told us about the local politics of moorings- how cousin Bob has two moorings, but never maintains them. And how he once received a gift of chain and line from a cruiser, but never shared any with Edward. Also how his brother Terry has two moorings, but sometimes places the boats he hosts on Edward's moorings (as was the case the morning we arrived). Not all is without competition! We gave Edward one of our Penn trolling polls and he was definitely surprised. "I did not expect this!" He immediately jammed it into a hole in the gunwale and said "I will put it here", then jumped aboard Shannon to chat.

Later, after making a trip to another boat, Edward returned to pick us up to go ashore.

Also in Edward's boat was another cruiser named Per from Sweden, who we had met in Fatu Hiva in the Marquesas when we anchored right next to him. Unbeknownst to us, he actually nearly died there from shallow water blackout while spearfishing, but was resuscitated with CPR by a doctor on a neighboring boat. Anyway, he was fine now and all smiles

. When we arrived at Edward's house, we could see that lunch preparations were under way, with a big table set in the shaded lanai. Alina and I wanted to go to the school to interview some kids for Reach the World, so we asked Edward and he radioed ahead to the school. At 12:30, Alina and I, along with some others, headed over to the school. But, not before sitting with grandma in the lanai, listening to her story of how she broke her leg in a crab hole on an outlying motu while packing a load of copra on her back... Then, how her foot was stuck in the hole with the bone bent backwards. After a long time, her son Simon came in a boat and picked her up to take her back to the village where he reset the bone and and splinted it with maori medicinal herbs (root of Pandanus). Every day she would massage the break in the ocean and apply more medicine. After a month she could hobble around the house. Now she has a visible divot in her shin, which she showed me by lifting leg up on the bench. Pretty flexible, old grandma. I asked her what had changed here on Palmerston since she was a child, and she said "Nothing is the same".. "Very different". When further prompted, she said that everyone used to be relaxed and not so uptight. Now everybody bickers and fights. She is 80 years old, so we assume she must be only 3rd or 4th generation Marsters.

At the school, all the kids were out at recess. We talked to the young friendly teacher's aid, and she snared a couple of kids for us to interview for RTW. Julianna, age 9, and Moe, age 9. Julianna preferred to stand up, and gave good answers to all questions. Moe, who seemed intimidated by the four questions he saw on my last page, got the abbreviated version. They seem very sheltered. Julianna did not seem to know any famous people, save for Michael Jackson, and when asked if she had any questions for kids in the U.S., it was "What kind of pizza do you have? I like cheese and chili"....

She liked all her subjects and wanted to be a teacher someday. And a hairdresser. When asked where she would go if she could go anywhere in the world, she answered "stay right here in Palmerston"...

After returning to Edward's from the school, we feasted on potluck lunch. Edward had cooked up some delicious ono (wahoo) which I ate!! and fried rice (which we brought), along with a couple of other dishes. Awesome.

Then it was another short walk with Edward to see a little more of the island (some pig pens and old graves and such), and then a short snorkel in the lagoon. The coral in the lagoon was awesomely healthy and everything looked quite pristine. Catamarans used to be able to make it through the pass into the lagoon, but the family council has since banned boats in the lagoon after one idiot cruiser repeatedly ignored Simon's requests and continued throwing their garbage in the water.

After getting out of the water and returning to Edward's house, Edward said "All four of you need to go to the admin office. Terry would like to speak with you." So Edward escorted us down there and Terry welcomed us into the office. Terry said "Sit down please". "I would like to speak with you regarding an incident that occurred today"..

My heart skipped a beat. Incident? "Oh shit, we're on a weird inbred island and now they're going to hold us prisoner, or frame us for some incident..."!

Turns out all he wanted was for us to go through the proper channels for visiting the school and interviewing the kids. (Which I assumed was asking permission from the teachers) He wanted to see our credentials (of which we of course had none) and to see the questions we asked the kids, along with their answers (which was a little Big-brother-ish). He asked if Reach the World was religiously affiliated, and when we said no, he seemed somewhat disappointed. He then told us how he received his masters in theology, which prepared him spiritually to come back to live on isolated Palmerston, but in no way did it prepare him practically for driving boats, fishing, etc.

I promised to return the next day with a copy of our interview, and all was well. Edward was somewhat apologetic for the dramatic nature of the meeting, but acknowledged that those rules were in place for the protection of the residents of Palmerston. Check.

Terry takes his job very seriously here on this small island, and I respect that. Still, it was a little scary.

Edward dropped us back off at Shannon before dinner, and for a reason unbeknownst to us, also dropped off his son Davie and cousin John on the Shannon. I didn't even realize it until I popped my head back out of the hatch after dropping my stuff in the cabin only to those two standing on the bowsprit looking like scared puppies. So, we all hung out in the cockpit, ate cookies and listended to music from Ken's Ipod. They specifically requested hiphop, so we played them the good old Hot 93.9 mix. We talked for more than an hour, with no clue as to where Edward had gone, or if he was even coming back that night.

I asked Davie if they ever get tired of sailors coming to their island day after day year after year, and he answered with an unequivocal "No, not at all." "It is no problem, and it is our custom to welcome visitors". No kidding. They'd been feeding us, ferrying us around in their boats, having us in their home, and all for nothing. Nobody ever once asked for a contribution, donation, or anything. Awesomeness.

9/10/10

I awoke to the sound of an outboard motor, and poked my head out of the companionway in time to see Edward drift past, madly reeling in his trolling line. With a grin he glanced over at me and yelled "Got away!"

He immediately came over and tied up to Shannon and hopped aboard.

"Good morning my friend!" he said