Voyages with Rosie

Alex Morton's Sailing Stories

28 March 2007

28 March 2007

28 March 2007

28 March 2007

28 March 2007

09 November 2006

26 October 2006

25 October 2006

Across the Great Divide

28 March 2007

A Primer for Crossing the Strait of Georgia

By

Alex Morton

Sure ... we know what we're doing. We've read the books, sailed the great oceans of literature with Chichester, the Smeetons, Slocum, and that lunatic Moitessier who didn't finish a round-the-world race because he decided to go round again. We can relate, right? Maybe we've been sailing with friends a few times, taken twelve hours of lessons, and day-chartered a Catalina 27 a few times. Who could be more ready for owning a sailboat, and setting out on great voyages?

The wife has finally come around to seeing how good an investment a sailboat can be at this time and has given the royal nod. Before something happens, you quickly run out and buy the first boat that looks like it knows more than you. No doubt, there's a wide range to choose from.

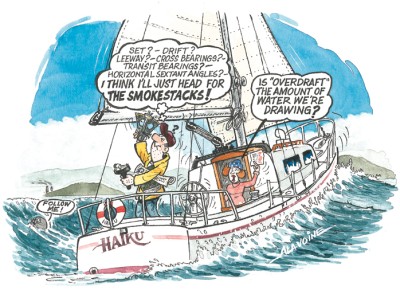

Ignoring the surveyor's advice that you might be better off buying a bathtub with a torn handkerchief for a sail and a one-bladed eggbeater for a power plant, you quickly drain half the contents of the bank account. You'll be back to the well many times. By the time you become a true sailor, you'll have become quite familiar with the term "overdraft".

Once the engine, mainsail, head, and batteries have been replaced, you'll take up the sailor's life in earnest, beginning with the purchase of bumpers, lines, solar showers, cushions and never quite reaching an end. It's what they call an all-encompassing hobby. It'll take everything you've got.

Somewhere between trips to marine supply stores, you might manage to get in a few sails. Maybe even enough to convince you that you're ready for your first ocean voyage across the Strait of Georgia, or as I call it, "the great divide". Never mind that it is only twenty-seven miles across and protected from the real ocean by that giant hunk of breakwater known as Vancouver Island, the first time across, it's as broad as the entire Pacific. I refer to it as "the great divide" because it divides Vancouver's novice sailors into two categories; those who've been truly scared and those who haven't yet made the crossing. In this world of vicarious pleasures, where the most exciting adventures are most often to be found on a computer screen, this one is for real. And you don't want to miss it!

If you leave from Horseshoe Bay, as I did, it's somewhere in the neighbourhood of twenty-seven miles to Gabriola Island and the security of Silva Bay. I chose the well-protected and facilities-rich destination because it didn't require traversing one of the narrow passes that demand careful timing in order to arrive at slack tide. Even though I'd calculated it all, I never have really trusted my math ever since I had that bout with Algebra in high school, and I didn't want to get an F for getting to a place at a specific time. Sometime before dark was as close as I needed to make it for Silva Bay, and that felt just about right.

According to the chart, after you get across the Strait, all you need to do to reach Silva Bay, is thread your way in and around the Flat Top islands, and follow a little channel for maybe a hundred meters. At the end of the rainbow, there would be a pool, hot tub, and a whole island full of solid ground.

Before I attempted it for the first time, I signed up for a coastal navigation course and even managed to attend a few classes before business travel made it impossible for me to continue. Still, I managed to absorb the basics; the use of a hand-bearing compass, triangulation, chart-reading, a bit about currents and tides, and the strong suggestion that we back up our calculations with an electronic aid. I'd also bought a copy of Bowditch's, the cruising guide to the Gulf Islands, enough charts to find my way to Oahu, and a fascinating book on navigating by either the zodiac or the stars. I forget which.

We stocked the Haiku with enough food and water to survive a month of becalming, a fuel supply that would get us through several days of non-stop motoring, and a large bunch of bananas for a Border Collie who figures that since her intelligence is right up there with the primates, she might as well eat like one.

On an early summer morning, we pushed out of Horseshoe Bay, heading for the great beyond. Anxious to avoid a time-consuming upwind beat through the fluky winds of the Queen Charlotte Channel, I didn't raise the sails until we reached Passage Island, and were entering the Strait. My wife handled the helm and mainsheet, as I stood beside the mast, raising the mainsail. There was a light chop developing that kept me dancing as I next hanked on the working jib, fumbled with bowlines to tie on jib sheets, clipped on the halyard and hauled away, feeling pretty damn good that I had done it right.

My wife juggled the jib sheet, winch and wheel as if she were born to it, as we headed out of the channel into the brisker winds and lumpier sea of the Strait. She turned off the engine, while I stood at the bow for a minute congratulating myself for getting the jib on right side up.

"What's the course, captain?" came a call from the helm.

Oh yeah. What was the course?

The chop was beginning to get a bit bigger as I made my way back to the cockpit, hanging onto the grab rail as I bounced around. I still hadn't gotten around to financing a roller-furling jib, and now I was paying the price.

Asking my wife to "hold her steady", I went below to check our location. The electronic navigation in use at the time was Loran, a cranky and oftentimes inaccurate precursor to GPS. Since mine at that moment showed my location as being somewhere off the coast of Manitoba, I thought it would be prudent to revert to the hand bearing compass and a more accurate form of navigation. Theoretically, I could figure out our position if I could identify two known geographic points, but theoretically, I could also swim to Honolulu, so I rightly began to feel a little trepidatious. But I had a solution. After years in high tech, I'd learned the maxim that when you feel insecure you should immediately surround yourself with equipment.

I might not have had a Loran with a realistic view of the world, but I did have a gleaming pair of dividers, a set of parallel rulers, sixteen sharpened number # 9 pencils, a complicated plastic wheel that was supposed to do something or other, a hand bearing compass, a log book, the cruising guide, the guide to navigation, a big white book of tide charts, and the book on navigating by either the zodiac or the stars. There was even a sextant, that my wife had given me for Christmas, sitting in a box at the peak of the vee berth. Just about as far away as possible, but it didn't matter since I still hadn't a clue how to use it. Most importantly, I had the advice of a friend who'd been sailing for years. "Just look for the two big smokestacks at Nanaimo. Worst case, if you get lost, you can put in there." As they taught in the navigation course that I almost finished, there's nothing like local lore to round out your navigation.

I sat at the chart table, also known as the dinner table, breakfast nook, and the place Rosie hides under when the weather gets rough (and won't even be tempted out of with a banana), and stared at the chart, remembering the steps I should be taking.

When I finally sorted it all out, I realized that all I had to do was point a straight edge on the chart from Horseshoe Bay to Silva Bay, and then walk the parallel rulers over to the compass rose to figure out our heading. After a few side trips, I managed to conquer walking in the right direction and arrived at our course. I knew I should be doing something about tide and drift, but I figured I could catch up with that later on with a quick course adjustment.

Feeling on a par with Tristan Jones, I climbed back up through the companionway with a course and an optimistic attitude. While I'd been dealing with navigation, I'd noticed that we were beginning to bounce around. By the time I got up on deck, we were being hit on the beam by some rollers coming down the Strait, and the winds had increased to twelve knot winds.

"Wow!", I thought, "A gigantic storm!"

Over the years, since that first sail across the Strait, I've realized that a sailboat is one of the few things that can scare the hell out of you at six miles an hour. People may be able to run faster than that on land, but when you're out there on the sea, heeled way over, and hanging on for dear life, it's definitely faster than you've ever been in a jet. And that's part of why we do it, because you sure as hell can't get the same kind of feeling watching something on TV or even going to the hockey game. It's all a matter of perspective, like seeing a port on a chart versus actually finding it.

The rollers began to make us rock, uncomfortably, which caused Rosie to head for her most secure spot on the boat, the vee berth, which was swathed in blankets, pillows and sheets. Perfect for a border collie who thought she was akin to the primates, but was acting like a purebred chicken.

It wasn't really very bad, but we made the most of it. My wife went below and brought up the thermos of hot tea and a pile of sandwiches we'd stowed for just such an occasion, while I stayed at the helm, automatically pointing Haiku's nose a bit into the rollers to dampen our own rolling. I didn't think much about navigation, except for trying, vaguely, to keep the compass pointed where it was supposed to be. Worst case, I figured, if I wound up too far North, I could always follow my friend's advice and follow the smokestacks to Nanaimo. Come to think of it, though, I never did see those smokestacks.

Instead, every few minutes I'd point the hand bearing compass at a couple of possibly recognizable objects in the distance, calculate what might be our position, and run below to plot it on the chart. According to the wiggly line, we seemed to be pointing pretty much in the right direction, and after a while I began to gain confidence, until, as we neared land, I was confronted with another problem. What was that directly in front of us? It seemed smeared there, rather than clearly defined as it was on the chart.

Frantically, I took bearings on every known object, scribbled down the results in a notebook, raced below, and plotted it out on the chart. Since the Loran at that point showed us to be on the outskirts of Houston Texas, there was no choice but to trust my coastal navigation. According to my calculations, I'd somehow managed to reach the Flattop islands that mark the entrance to Silva Bay. But it all looked weird. One of the most startling revelations for the neophyte sailor occurs the first time you sail to a new place guided by a chart and realize that in real-life you're looking across at the land instead of down. It just doesn't look the same. It's a heck of a lot harder to see all the nooks and crannies of the shoreline when you're on eye-level with them, rather than getting the helicopter view that's portrayed on a chart.

At that point, Rosie staggered on deck and gave me the Border Collie stare that means one of three things; she was hungry, needed a walk, or was trying to express her frustration over not having opposable thumbs. Fortunately, a banana seemed to placate her, and she went back to her nest in the vee berth to await solutions for her other issues.

The only strategy that made sense regarding navigation, was to trust my calculations. Not since I turned in the final exam in algebra have I had to rely on my mathematical abilities for such a weighty matter. Luckily, I did manage to squeak through algebra, and even geometry and some other stuff that gives me the willies to this day, so having found the right islands wasn't completely out of the question.

We dropped the sails on deck, and one of our solar showers overboard, started the engine, hoped the rumours of hot showers at Silva Bay were true, and wiggled our way through the islands, guessed at the channel that led to the bay, and followed the cruising guide's suggestions that we avoid the rocks. I radio'd in to the marina to announce our presence to the waiting natives and motored slowly toward our landfall.

Suddenly, the world of uncertainty was left behind. Understandable slips beckoned us, and an empathetic wharfinger stood on the dock to guide us in. Rosie came back on deck, stretched a few times, barked once at the wharfinger to announce that she was taking over, and made her way up to the bow.

We were there! We'd crossed the great divide and survived. Maybe, like Moitessier, one day we'll just keep going and never turn back. Someday. Just as soon as I learn how to use the sextant.

Comments

| Home Page: | www.alexmortonwriter.com |

Album: Main | Voyages with Rosie

No items in this gallery.