- PHOTOS:

- Dec 16, 2008 - May 21, 2009

- Mar 17, 2008 - Dec 15, 2008

- Nov 01, 2007 - Mar 16, 2008

- Our SC35 Sailboat: PRUDENCE

- SELECTED BLOGS

- Jan'05: The Idea

- May'05: First Cruise - Belize

- Aug'05: Buying Ashiya

- Oct'05: School in St. Vincent

- Nov'05: Ocracoke on Ashiya

- Jul'06: Long Trip on Ashiya

- Oct'06: Prudence Comes Home

- Nov'07: First Night Offshore

- Nov'07: Offshore Take Two

- Nov'07: Gulf Stream Crossing

- Dec'07: Green Turtle Cay

- Dec'07: Lynyard Cay

- Dec'07: Warderick Wells Cay

- Jan'08: George Town

- Jan'08: Life without a Fridge

- Jan'08: Mayaguana Island

- Jan'08: Turks & Caicos

- Jan'08: Dominican Republic

- Jan'08: Down the Waterfalls

- Feb'08: Puerto Rico

- Feb'08: Starter Troubles

- Feb'08: Vieques

- Mar'08: Finally Sailing Again

- Mar'08: Trip So Far

- Mar'08: Hiking Culebra

- Mar'08: Kayak & Snorkel I

- Mar'08: Teak and Waterspouts

- Mar'08: Kayak & Snorkel II

- Mar'08: Bottom Cleaning

- Apr'08: Culebra Social Life

- Apr'08: Culebra Routine

- Apr'08: Culebra Beaches

- Apr'08: Culebrita

- Jun'08: Kayak & Snorkel III

- Jun'08: Kayak & Snorkel IV

- Jun'08: Manta Ray

- Jun'08: Sea Turtles

- Jul'08: Cost of Cruising

- Jul'08: Busy Week in Culebra

- Jul'08: Getting to Land

- Jul'08: Leatherback Boil

- Jul'08: Fish and Volcano Dust

- Aug'08: Teaching Algebra

- Sep'08: Culebra Card Club

- Oct'08: Kayak & Snorkel V

- Oct'08: Prep for Hurricane

- Oct'08: Hurricane Omar

- Oct'08: Fish and Sea Glass

- Oct'08: Waterspouts

- Dec'08: Hurricane Season Ends

- Dec'08: Culebra to St. Martin

- Jan'09: Antigua Part 1

- Feb'09: The Saints

- Feb'09: Visiting Dominica

- Mar'09: Antigua Part 2

- Apr'09: Antigua to Bermuda

- May'09: Bermuda to Norfolk

- FULL LIST of Blog Entries

15 July 2009

14 July 2009

15 June 2009

14 June 2009 | Annapolis, MD

13 June 2009

12 June 2009

11 June 2009

10 June 2009 | Little Creek Marina, Norfolk, VA, USA

04 June 2009 | Little Creek Marina, Norfolk, VA, USA

31 May 2009 | Little Creek Marina, Norfolk, VA, USA

29 May 2009 | Little Creek Marina, Norfolk, VA, USA

26 May 2009 | Little Creek Marina, Norfolk, VA, USA

25 May 2009 | Little Creek Marina, Norfolk, VA, USA

13 May 2009 | through 21-May-2009

13 May 2009 | through 21-May-2009

12 May 2009 | St George's Town, Bermuda

11 May 2009 | St George's Town, Bermuda

07 May 2009 | St George's Town, Bermuda

04 May 2009 | St George's Town, Bermuda

21 April 2009 | through 02-May-2009

No Anguillan Souvenirs for Us, Thanks: The Passage to Antigua

23 January 2009 | From Marigot, St. Martin to Jolly Harbour, Antigua

CURRENT LOCATION: Anchored in Mosquito Cove, just outside Jolly Harbour in Antigua

17 04.579' N, 061 53.613' W

Some passages are wonderful, like sailing on a single tack from Culebra to St. Martin, and some passages are not so wonderful. This is a tale of the latter. In fact, this appears to be a trend for us. Those crossings which have a reputation for being nasty, like the Mona Passage or the Oh-My-Godda Passage turn out to be kittens. Whereas, the lesser-advertised crossings from the Turks and Caicos to the Dominican Republic and this current passage are crouching tigers and hidden dragons.

Nothing bad happens in this story, but it just wasn't the easy-island-hopping-reaching-on-tradewinds sailing we had been hoping for. In retrospect, I suppose that the lesson learned is not to set your expectations too high. With our trip to St. Martin, we were expecting a rough ride and several days at sea. We did it comfortably in 28 hours. For this passage, we expected to be able to do it with a single night at sea (in under 36 hours) and experience just a few tacks in comfortable sea conditions. As you will see, we were wrong. But I am getting ahead of myself, so let me start where I left off in the last blog...

Tuesday, Jan 20th - The day before departure:

We said goodbye to St. Martin with a visit to Fort Louis. From this vantage point we had some fantastic views of Marigot Bay (where Prudence is anchored) and the lagoon.

Following one more trip to two more supermarkets (we believe we now have enough wine, in boxes rather than bottles, to hold us until the next French island), we did the last of the pre-preparation chores. This included deflating the dinghy and rigging the wind vane steering. We would be ready to depart at first light, and say goodbye to the French experience for a while.

Wednesday, Jan 21st - The first day at sea:

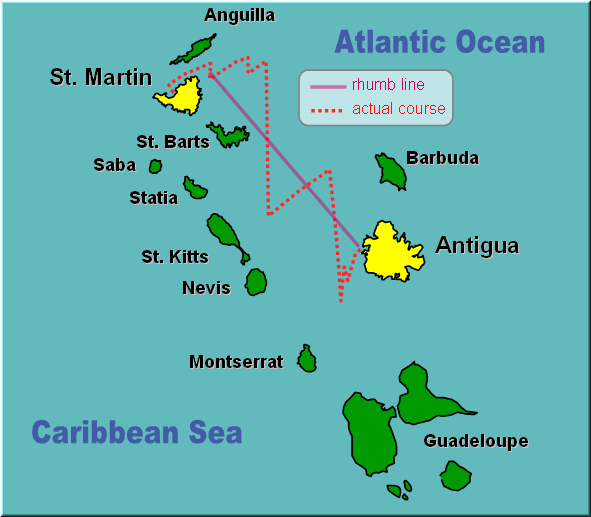

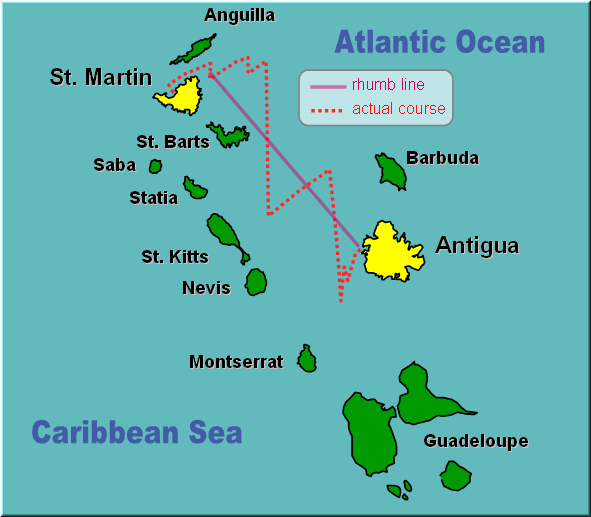

Our plan was to run the engine for the first two hours to help us get around the northern end of St. Martin. In addition to getting us quickly clear of the capes, this will also top off the batteries and get the engine nice and warm, should we need to start it later. Once we are past Tintamarre (a small island just east of Orient Bay) we will turn off the engine and do our best to run the rhumb line to Antigua. After two hours, the engine was off and we were under sail; however, as you can see below the rhumb line isn't exactly the course we maintained.

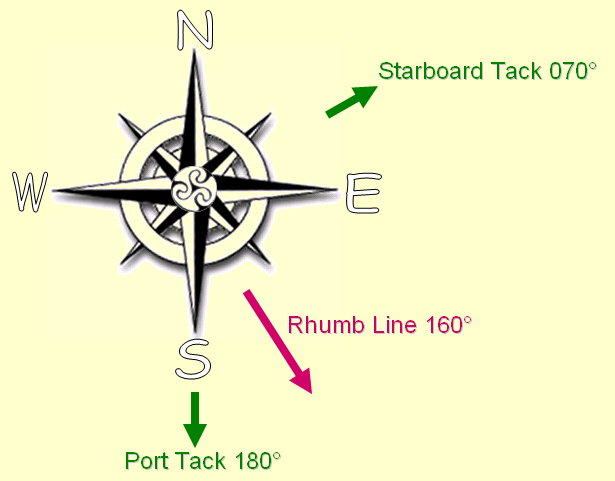

The reason for this is basic sailing physics. A sailboat cannot sail directly to windward. Instead, you must keep the apparent wind at least 45 degrees off the direction the boat is pointing in order to keep the sails full of wind and shaped sufficiently to pull the boat through the water. So, in order to get to Antigua, we had to turn the boat on different tacks (directions), with the wind on either side, and zig-zag our way to the southeast.

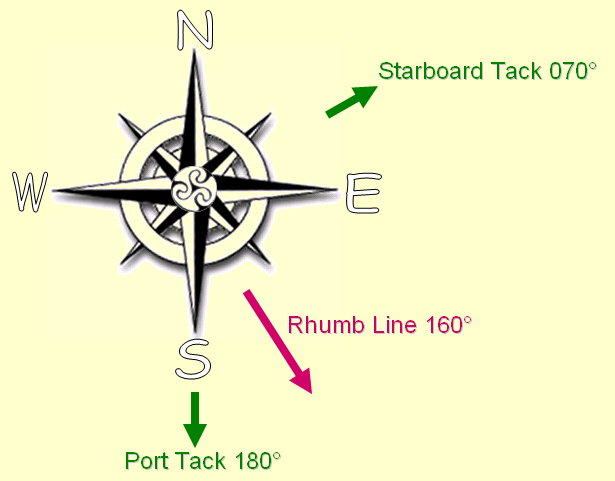

On a starboard tack we could do a heading of about 70 degrees true (just north of east), while on a port tack we could do 180 degrees (due south):

Under ideal conditions, the angle between each tack is a little tighter (more like 95-100 degrees for our boat), but several aspects of the sea state conspired to broaden that gap today. The first is the current, which was flowing in a northwesterly direction. Although it was likely less than 1 knot of current, this is sufficient to push our boat sideways as we slowly move through the current perpendicular to its flow. The second is the waves. Today the sea state was predicted to be about 10 feet in an easterly swell. This is not too big a factor when the winds are reasonable in magnitude and we are out in deep, deep water; however, in the shallow water surrounding some of these islands, the waves can get closely packed and sharply pointed. As we pound though these waves, the boat is pushed back or sideways.

In all the basic sailing textbooks I have perused, I don't recall the effects of wave and current being highlighted. Surprisingly so, for these 'sea conditions' effect the quality of our sail as much as the status of the winds. Today the sea conditions were the villains that cost us precious extra degrees away from our desired rhumb line course. And, over a long distance, every little degree translates to extra hours at sea.

Our first few tacks took place where the Anguilla Channel opens to the Atlantic Ocean. It was here that we met what was to be the biggest villain of this journey, Anguillan fishermen. Actually, we did not meet them, per se, instead we encountered their handiwork. I sighted the first pair of small floating buoys off our starboard side at about 10AM. From our experience sailing in the Neuse River we are familiar with the same type of floats used on crab pots. Here, we believe that they mark fishing nets. Hopefully, the nets hang low enough that our keel would not snag them (I really don't know what exists below the waterline). But we do know what is waiting to cause trouble for us on the surface. The floats always appear in pairs which are tied together with about 20-30 feet of line. It is this stretch of line lying right upon the surface of the water which we are worried about. Not only do we have a keel and a skeg which could snag this line, we are also dragging the rudder for our windvane steering behind the boat.

So, upon sighting the first buoy Sheryl jumps into lookout mode. Perched at the bow (holding onto the bow pulpit for dear life as she is repeatedly rocketed up and down 10-15 feet), she spots and points out more buoys in each direction. I am at the helm, trying to avoid traveling between the buoy pairs. Easy to do with only one, a real challenge when there are dozens. And, we are under sail which is currently making 110 degrees of steerage (nearly one-third of the full 360) off limits. Turning on the engine is not an option, because as much as we would hate to snag one of these under sail, it would be even worse to wrap one around the prop.

That is not to say that snagging one under sail would be a minor thing. As my mind conjured a worst case scenario, it was not hard to imagine catching one of these lines with our keel. Because our boat moves so slowly anyway, this would likely slow us to the point of loosing steerage. We would be adrift in a current which is pushing us toward the reef-laden shores of Anguilla (only a few miles to our northwest). The big, sloppy seas may also help push the boat toward that dangerous lee shore and would most certainly make cutting the offending line that much more challenging. I would be engaged in a game of beat the clock to get into a safety harness, tether myself to the boat, dive below with a knife and free the line from the boat. Worst case scenario also considers that with the density of these nets, we would be likely pick up one or two more while we were drifting along trying to free the first. We took great efforts to make certain that this scenario would not play out in living color. We preferred to collect no Anguillan souvenirs.

So, it was a painstaking day of watching for buoys and trying to make adjustments to our course. This is made ever more challenging by the fact that the boat is moving sideways. It is not so noticeable when you are without a point of reference, but as you approach these buoys you realize that the boat is not moving in a straight line in the direction the bow is pointing. Therefore, buoys spotted on the leeward side of the boat deserved special attention. Do we fall off or try to hold course close to the wind and hope to pass them before we drift into them? Nerves were rattled and we were fatigued by the time the day's sun was preparing to set. Fortunately, the final tack of the day (away from Anguillan waters) seemed to leave the buoys behind. With the darkness settling in, we resolved to accept whatever happens overnight. There would be no buoy spotting in the absence of moonlight (the full moon is about two weeks away). At least we had gained distance from dangerous lee shores.

The early daylight hours had brought some serious squalls over us before we entered the buoy minefield and our first hours into darkness brought yet another set of squalls. Winds ranged from zero to 25 knots in as little as a minute, and I was continually interrupted in my attempts to make dinner in order to help with changes in sail configuration. Deciding how much sail to fly at any point in time was just a little more stress heaped on our tired shoulders.

After weathering a thoroughly exhausting day of squalls and dodging buoys, we were treated to a very nice overnight sail. A billion stars came out in the wake of the storm clouds, and the winds settled to a pleasant and consistent 15 knots. We set the windvane steering (which we call SUE) and let her steer us south through the night. The seas were rough, but even with reduced sail we had enough speed to push through them. The constant crashing and jolting did make obtaining any meaningful sleep a rather impossible feat.

We slowly left the lights of St. Barts behind and approached the lights of St. Kitts. In an effort to keep my mind busy, I often look at the numbers provided on the GPS screen and try to determine the speeds we will need to maintain to achieve a specific arrival time. Initially, although we departed with winds out of the southeast, I had hoped that an expected wind shift to the east would occur and bring us around to our rhumb line. The wind shift had yet to happen and we continued to push directly south. In the morning, we were going to have to discuss our options. We both wanted to arrive before sunset on Thursday, because the approach to Antigua is not one to be undertaken in the dark of a moonless night. If we couldn't get there in time, it would mean another night at sea.

Thursday, Jan 22nd - The second day at sea:

With the morning's first light, we tacked to the northeast and rolled out all the sails. We wanted to give it our all to make our arrival before sunset. However, by 9AM it was obvious that we were not going to make it. The sea state was incredibly rough and despite good sailing winds we were being slowed with each pounding. Looking at the chart, we considered going instead to Barbuda. We were headed in that general direction, and there is an anchorage along the west coast which should provide good protection in these weather conditions. Again, we would have to arrive well before sunset, due to the need to spot coral heads on our approach, but it would beat another night at sea.

We read a little about Barbuda (at least as much as one can read on a boat which is bucking like a bronco and bound to inflict sea sickness on anyone, including me), and warmed to the idea of staying and exploring that island for a few days. With a new waypoint in the GPS, it was going to be close, but I thought we could make it. We would have to turn on the engine for the last six hours, but with engine and full sails we should be able to push through these waves and make it there in time. It was 11AM when we sighted the familiar buoys floating in the water (I guess Anguillans aren't the only ones fishing the waters around these islands). After an hour of evasive maneuvers it was obvious that we were not inclined to turn on the engine, for fear of prop wrap, and were thus unlikely to make it to Barbuda before dark.

So, we reduced sail and reluctantly accepted that we were going to spend another night at sea. The destination on the GPS was changed back to Antigua, and we had plenty of time to get there. A first light arrival meant that we would probably have to stall off the coast of Antigua in the wee hours of the morning. We were in no hurry to get there and the pounding of these rough seas would be a little easier to take if we were moving a little slower.

As we headed on another long southbound tack, the winds shifted slightly more to the east giving us a better heading toward our destination. The buoys, thankfully, disappeared. Only a little too late for us to take advantage of the better course, wouldn't you know it. At least the second invasion of the buoys lasted only a short while, they were beginning to make us angry. The afternoon became evening as SUE steadily steered us onward.

We arrived about 12 miles off the west coast of Antigua at 10PM. The conditions were perfect for stalling about. Winds decreased to 8-12 knots and we shortened sail even further. Several lazy tacks in slightly more comfortable seas found us decreasing the distance between us and shore by about 6 miles over the course of 6 hours. During that time, Sheryl even let me have an extra hour of sleep past the start time for my final shift at the helm. This is probably the most generous gift one exhausted cruiser can give to another. I truly love my wife, my captain, my sailing partner for life.

Friday, Jan 23rd - Arrival in Antigua:

Armed with this invigorating rest, I took the helm at 4AM and tacked toward land. Dawn's early light revealed the island of Antigua, and we finally turned on our engine again to help guide us to the anchorage. Our guidebook suggested an anchor spot in The Cove. There were no boats there, so we selected a spot and set our anchor in 8 feet of sand.

I assembled the dinghy while Sheryl began the process of converting our blue water transport back into a home. Once assembled, Sheryl took Patience to the Customs dock to clear us in. Here, Sheryl is considered the Master of our vessel rather than the Captain. I remain the ever-humble Crew. While the master and commander of Prudence was ashore, I used the last of my remaining energies to clean up. Over the past 48 hours, dirty dishes had accumulated, the floors below were slick with the residue of salt, and the air was stale. By the time Sheryl returned, our home was a little more inhabitable.

Immediately upon her return, we decided to move the boat to a different spot, just a short distance away. Although it was not listed in the guidebook, there were other boats anchored in Mosquito Cove, on either side of the entrance to Jolly Harbour. We chose the left bank and re-anchored in 7 feet of water. Here it is a little less exposed to chop and swell. In fact, it is the calmest anchorage we have experienced in over a month. The little bit of swell currently making its way in is hitting us directly astern, and is barely noticeable.

With the second anchoring complete, I was ready for a shower and a nap. I awoke in the late afternoon/early evening, and Sheryl apologized for having eaten dinner without me but she was hungry. I indicated that it was no problem, and we would get back into our routine again soon. As she set a delicious bowl of Asian seasoned broccoli, carrots, and rice before me she inquired, "Mack truck?" In the special language that couples often develop, she was asking if I was feeling sore from the passage. Constant conditions of heeling and jarring as the boat smashes through waves often leave one feeling as though you have been hit by a Mack truck. "Yep," I replied. "Me too," she indicated. If the motion of the boat at anchor encourages isometric exercise, the motion of the boat in rough seas is tantamount to isometric abuse. Even our hands hurt from constantly having to hold on to something. It will be several days before the aching subsides.

Together we watched the sun set from the cockpit. In all our anchorages, we have never had a view of the sunset across an expanse of open water. It was brief, and we may have even imagined it in our fatigued state, but the elusive green flash appeared as the last of the yellow orb dipped below the line of the horizon. Hopefully, we will see a repeat performance to confirm these observations over the next several days. Perhaps, if luck is on our side, we might even grab photographic evidence. Until then, this shot of the sun melting into the sea will just have to do.

Passage Stats:

Rhumb line course: 100 nautical miles

Actual course: 183.7 nautical miles

Passage time: 48 hours

Engine hours: 4 hours (fuel consumed estimated to be less than 2 gallons of diesel)

17 04.579' N, 061 53.613' W

Some passages are wonderful, like sailing on a single tack from Culebra to St. Martin, and some passages are not so wonderful. This is a tale of the latter. In fact, this appears to be a trend for us. Those crossings which have a reputation for being nasty, like the Mona Passage or the Oh-My-Godda Passage turn out to be kittens. Whereas, the lesser-advertised crossings from the Turks and Caicos to the Dominican Republic and this current passage are crouching tigers and hidden dragons.

Nothing bad happens in this story, but it just wasn't the easy-island-hopping-reaching-on-tradewinds sailing we had been hoping for. In retrospect, I suppose that the lesson learned is not to set your expectations too high. With our trip to St. Martin, we were expecting a rough ride and several days at sea. We did it comfortably in 28 hours. For this passage, we expected to be able to do it with a single night at sea (in under 36 hours) and experience just a few tacks in comfortable sea conditions. As you will see, we were wrong. But I am getting ahead of myself, so let me start where I left off in the last blog...

Tuesday, Jan 20th - The day before departure:

We said goodbye to St. Martin with a visit to Fort Louis. From this vantage point we had some fantastic views of Marigot Bay (where Prudence is anchored) and the lagoon.

Following one more trip to two more supermarkets (we believe we now have enough wine, in boxes rather than bottles, to hold us until the next French island), we did the last of the pre-preparation chores. This included deflating the dinghy and rigging the wind vane steering. We would be ready to depart at first light, and say goodbye to the French experience for a while.

Wednesday, Jan 21st - The first day at sea:

Our plan was to run the engine for the first two hours to help us get around the northern end of St. Martin. In addition to getting us quickly clear of the capes, this will also top off the batteries and get the engine nice and warm, should we need to start it later. Once we are past Tintamarre (a small island just east of Orient Bay) we will turn off the engine and do our best to run the rhumb line to Antigua. After two hours, the engine was off and we were under sail; however, as you can see below the rhumb line isn't exactly the course we maintained.

The reason for this is basic sailing physics. A sailboat cannot sail directly to windward. Instead, you must keep the apparent wind at least 45 degrees off the direction the boat is pointing in order to keep the sails full of wind and shaped sufficiently to pull the boat through the water. So, in order to get to Antigua, we had to turn the boat on different tacks (directions), with the wind on either side, and zig-zag our way to the southeast.

On a starboard tack we could do a heading of about 70 degrees true (just north of east), while on a port tack we could do 180 degrees (due south):

Under ideal conditions, the angle between each tack is a little tighter (more like 95-100 degrees for our boat), but several aspects of the sea state conspired to broaden that gap today. The first is the current, which was flowing in a northwesterly direction. Although it was likely less than 1 knot of current, this is sufficient to push our boat sideways as we slowly move through the current perpendicular to its flow. The second is the waves. Today the sea state was predicted to be about 10 feet in an easterly swell. This is not too big a factor when the winds are reasonable in magnitude and we are out in deep, deep water; however, in the shallow water surrounding some of these islands, the waves can get closely packed and sharply pointed. As we pound though these waves, the boat is pushed back or sideways.

In all the basic sailing textbooks I have perused, I don't recall the effects of wave and current being highlighted. Surprisingly so, for these 'sea conditions' effect the quality of our sail as much as the status of the winds. Today the sea conditions were the villains that cost us precious extra degrees away from our desired rhumb line course. And, over a long distance, every little degree translates to extra hours at sea.

Our first few tacks took place where the Anguilla Channel opens to the Atlantic Ocean. It was here that we met what was to be the biggest villain of this journey, Anguillan fishermen. Actually, we did not meet them, per se, instead we encountered their handiwork. I sighted the first pair of small floating buoys off our starboard side at about 10AM. From our experience sailing in the Neuse River we are familiar with the same type of floats used on crab pots. Here, we believe that they mark fishing nets. Hopefully, the nets hang low enough that our keel would not snag them (I really don't know what exists below the waterline). But we do know what is waiting to cause trouble for us on the surface. The floats always appear in pairs which are tied together with about 20-30 feet of line. It is this stretch of line lying right upon the surface of the water which we are worried about. Not only do we have a keel and a skeg which could snag this line, we are also dragging the rudder for our windvane steering behind the boat.

So, upon sighting the first buoy Sheryl jumps into lookout mode. Perched at the bow (holding onto the bow pulpit for dear life as she is repeatedly rocketed up and down 10-15 feet), she spots and points out more buoys in each direction. I am at the helm, trying to avoid traveling between the buoy pairs. Easy to do with only one, a real challenge when there are dozens. And, we are under sail which is currently making 110 degrees of steerage (nearly one-third of the full 360) off limits. Turning on the engine is not an option, because as much as we would hate to snag one of these under sail, it would be even worse to wrap one around the prop.

That is not to say that snagging one under sail would be a minor thing. As my mind conjured a worst case scenario, it was not hard to imagine catching one of these lines with our keel. Because our boat moves so slowly anyway, this would likely slow us to the point of loosing steerage. We would be adrift in a current which is pushing us toward the reef-laden shores of Anguilla (only a few miles to our northwest). The big, sloppy seas may also help push the boat toward that dangerous lee shore and would most certainly make cutting the offending line that much more challenging. I would be engaged in a game of beat the clock to get into a safety harness, tether myself to the boat, dive below with a knife and free the line from the boat. Worst case scenario also considers that with the density of these nets, we would be likely pick up one or two more while we were drifting along trying to free the first. We took great efforts to make certain that this scenario would not play out in living color. We preferred to collect no Anguillan souvenirs.

So, it was a painstaking day of watching for buoys and trying to make adjustments to our course. This is made ever more challenging by the fact that the boat is moving sideways. It is not so noticeable when you are without a point of reference, but as you approach these buoys you realize that the boat is not moving in a straight line in the direction the bow is pointing. Therefore, buoys spotted on the leeward side of the boat deserved special attention. Do we fall off or try to hold course close to the wind and hope to pass them before we drift into them? Nerves were rattled and we were fatigued by the time the day's sun was preparing to set. Fortunately, the final tack of the day (away from Anguillan waters) seemed to leave the buoys behind. With the darkness settling in, we resolved to accept whatever happens overnight. There would be no buoy spotting in the absence of moonlight (the full moon is about two weeks away). At least we had gained distance from dangerous lee shores.

The early daylight hours had brought some serious squalls over us before we entered the buoy minefield and our first hours into darkness brought yet another set of squalls. Winds ranged from zero to 25 knots in as little as a minute, and I was continually interrupted in my attempts to make dinner in order to help with changes in sail configuration. Deciding how much sail to fly at any point in time was just a little more stress heaped on our tired shoulders.

After weathering a thoroughly exhausting day of squalls and dodging buoys, we were treated to a very nice overnight sail. A billion stars came out in the wake of the storm clouds, and the winds settled to a pleasant and consistent 15 knots. We set the windvane steering (which we call SUE) and let her steer us south through the night. The seas were rough, but even with reduced sail we had enough speed to push through them. The constant crashing and jolting did make obtaining any meaningful sleep a rather impossible feat.

We slowly left the lights of St. Barts behind and approached the lights of St. Kitts. In an effort to keep my mind busy, I often look at the numbers provided on the GPS screen and try to determine the speeds we will need to maintain to achieve a specific arrival time. Initially, although we departed with winds out of the southeast, I had hoped that an expected wind shift to the east would occur and bring us around to our rhumb line. The wind shift had yet to happen and we continued to push directly south. In the morning, we were going to have to discuss our options. We both wanted to arrive before sunset on Thursday, because the approach to Antigua is not one to be undertaken in the dark of a moonless night. If we couldn't get there in time, it would mean another night at sea.

Thursday, Jan 22nd - The second day at sea:

With the morning's first light, we tacked to the northeast and rolled out all the sails. We wanted to give it our all to make our arrival before sunset. However, by 9AM it was obvious that we were not going to make it. The sea state was incredibly rough and despite good sailing winds we were being slowed with each pounding. Looking at the chart, we considered going instead to Barbuda. We were headed in that general direction, and there is an anchorage along the west coast which should provide good protection in these weather conditions. Again, we would have to arrive well before sunset, due to the need to spot coral heads on our approach, but it would beat another night at sea.

We read a little about Barbuda (at least as much as one can read on a boat which is bucking like a bronco and bound to inflict sea sickness on anyone, including me), and warmed to the idea of staying and exploring that island for a few days. With a new waypoint in the GPS, it was going to be close, but I thought we could make it. We would have to turn on the engine for the last six hours, but with engine and full sails we should be able to push through these waves and make it there in time. It was 11AM when we sighted the familiar buoys floating in the water (I guess Anguillans aren't the only ones fishing the waters around these islands). After an hour of evasive maneuvers it was obvious that we were not inclined to turn on the engine, for fear of prop wrap, and were thus unlikely to make it to Barbuda before dark.

So, we reduced sail and reluctantly accepted that we were going to spend another night at sea. The destination on the GPS was changed back to Antigua, and we had plenty of time to get there. A first light arrival meant that we would probably have to stall off the coast of Antigua in the wee hours of the morning. We were in no hurry to get there and the pounding of these rough seas would be a little easier to take if we were moving a little slower.

As we headed on another long southbound tack, the winds shifted slightly more to the east giving us a better heading toward our destination. The buoys, thankfully, disappeared. Only a little too late for us to take advantage of the better course, wouldn't you know it. At least the second invasion of the buoys lasted only a short while, they were beginning to make us angry. The afternoon became evening as SUE steadily steered us onward.

We arrived about 12 miles off the west coast of Antigua at 10PM. The conditions were perfect for stalling about. Winds decreased to 8-12 knots and we shortened sail even further. Several lazy tacks in slightly more comfortable seas found us decreasing the distance between us and shore by about 6 miles over the course of 6 hours. During that time, Sheryl even let me have an extra hour of sleep past the start time for my final shift at the helm. This is probably the most generous gift one exhausted cruiser can give to another. I truly love my wife, my captain, my sailing partner for life.

Friday, Jan 23rd - Arrival in Antigua:

Armed with this invigorating rest, I took the helm at 4AM and tacked toward land. Dawn's early light revealed the island of Antigua, and we finally turned on our engine again to help guide us to the anchorage. Our guidebook suggested an anchor spot in The Cove. There were no boats there, so we selected a spot and set our anchor in 8 feet of sand.

I assembled the dinghy while Sheryl began the process of converting our blue water transport back into a home. Once assembled, Sheryl took Patience to the Customs dock to clear us in. Here, Sheryl is considered the Master of our vessel rather than the Captain. I remain the ever-humble Crew. While the master and commander of Prudence was ashore, I used the last of my remaining energies to clean up. Over the past 48 hours, dirty dishes had accumulated, the floors below were slick with the residue of salt, and the air was stale. By the time Sheryl returned, our home was a little more inhabitable.

Immediately upon her return, we decided to move the boat to a different spot, just a short distance away. Although it was not listed in the guidebook, there were other boats anchored in Mosquito Cove, on either side of the entrance to Jolly Harbour. We chose the left bank and re-anchored in 7 feet of water. Here it is a little less exposed to chop and swell. In fact, it is the calmest anchorage we have experienced in over a month. The little bit of swell currently making its way in is hitting us directly astern, and is barely noticeable.

With the second anchoring complete, I was ready for a shower and a nap. I awoke in the late afternoon/early evening, and Sheryl apologized for having eaten dinner without me but she was hungry. I indicated that it was no problem, and we would get back into our routine again soon. As she set a delicious bowl of Asian seasoned broccoli, carrots, and rice before me she inquired, "Mack truck?" In the special language that couples often develop, she was asking if I was feeling sore from the passage. Constant conditions of heeling and jarring as the boat smashes through waves often leave one feeling as though you have been hit by a Mack truck. "Yep," I replied. "Me too," she indicated. If the motion of the boat at anchor encourages isometric exercise, the motion of the boat in rough seas is tantamount to isometric abuse. Even our hands hurt from constantly having to hold on to something. It will be several days before the aching subsides.

Together we watched the sun set from the cockpit. In all our anchorages, we have never had a view of the sunset across an expanse of open water. It was brief, and we may have even imagined it in our fatigued state, but the elusive green flash appeared as the last of the yellow orb dipped below the line of the horizon. Hopefully, we will see a repeat performance to confirm these observations over the next several days. Perhaps, if luck is on our side, we might even grab photographic evidence. Until then, this shot of the sun melting into the sea will just have to do.

Passage Stats:

Rhumb line course: 100 nautical miles

Actual course: 183.7 nautical miles

Passage time: 48 hours

Engine hours: 4 hours (fuel consumed estimated to be less than 2 gallons of diesel)

| Vessel Name: | Prudence |

| About: |

Gallery not available

- PHOTOS:

- Dec 16, 2008 - May 21, 2009

- Mar 17, 2008 - Dec 15, 2008

- Nov 01, 2007 - Mar 16, 2008

- Our SC35 Sailboat: PRUDENCE

- SELECTED BLOGS

- Jan'05: The Idea

- May'05: First Cruise - Belize

- Aug'05: Buying Ashiya

- Oct'05: School in St. Vincent

- Nov'05: Ocracoke on Ashiya

- Jul'06: Long Trip on Ashiya

- Oct'06: Prudence Comes Home

- Nov'07: First Night Offshore

- Nov'07: Offshore Take Two

- Nov'07: Gulf Stream Crossing

- Dec'07: Green Turtle Cay

- Dec'07: Lynyard Cay

- Dec'07: Warderick Wells Cay

- Jan'08: George Town

- Jan'08: Life without a Fridge

- Jan'08: Mayaguana Island

- Jan'08: Turks & Caicos

- Jan'08: Dominican Republic

- Jan'08: Down the Waterfalls

- Feb'08: Puerto Rico

- Feb'08: Starter Troubles

- Feb'08: Vieques

- Mar'08: Finally Sailing Again

- Mar'08: Trip So Far

- Mar'08: Hiking Culebra

- Mar'08: Kayak & Snorkel I

- Mar'08: Teak and Waterspouts

- Mar'08: Kayak & Snorkel II

- Mar'08: Bottom Cleaning

- Apr'08: Culebra Social Life

- Apr'08: Culebra Routine

- Apr'08: Culebra Beaches

- Apr'08: Culebrita

- Jun'08: Kayak & Snorkel III

- Jun'08: Kayak & Snorkel IV

- Jun'08: Manta Ray

- Jun'08: Sea Turtles

- Jul'08: Cost of Cruising

- Jul'08: Busy Week in Culebra

- Jul'08: Getting to Land

- Jul'08: Leatherback Boil

- Jul'08: Fish and Volcano Dust

- Aug'08: Teaching Algebra

- Sep'08: Culebra Card Club

- Oct'08: Kayak & Snorkel V

- Oct'08: Prep for Hurricane

- Oct'08: Hurricane Omar

- Oct'08: Fish and Sea Glass

- Oct'08: Waterspouts

- Dec'08: Hurricane Season Ends

- Dec'08: Culebra to St. Martin

- Jan'09: Antigua Part 1

- Feb'09: The Saints

- Feb'09: Visiting Dominica

- Mar'09: Antigua Part 2

- Apr'09: Antigua to Bermuda

- May'09: Bermuda to Norfolk

- FULL LIST of Blog Entries