Birvidik

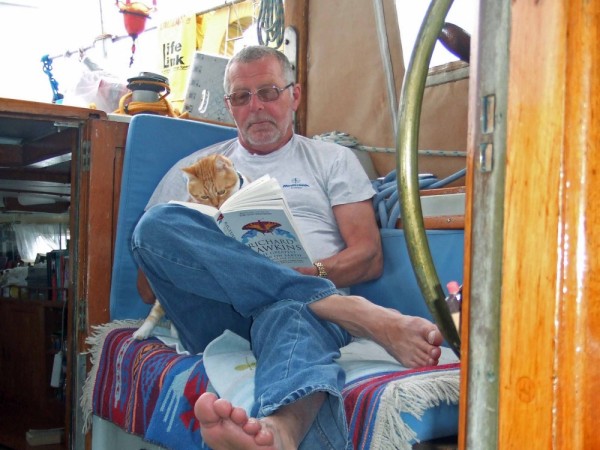

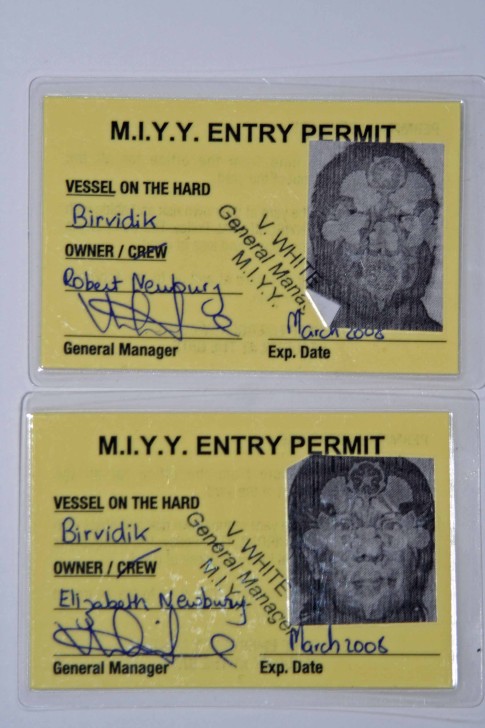

| Vessel Name: | Birvidik |

| Vessel Make/Model: | Victory 40 |

| Hailing Port: | Jersey C.I. |

| Crew: | Bob Newbury |

| About: | Liz Newbury |

| Extra: | 11 years into a 10 year plan, but we get there in the end. |

24 December 2023

22 November 2023 | Here I am, stuck in the middle with you.

14 August 2023 | A farce in three acts.

14 August 2023 | Sliding Doors

14 August 2023 | The Game Commences

14 August 2023 | or

11 March 2023 | Joseph Heller, eat your heart out.

24 December 2022

26 August 2022 | or 'French Leave'

03 August 2022 | or 'Fings ain't the way they seem'

18 June 2022 | or Desolation Row

22 March 2022 | or "Every Form of Refuge Has its Price

22 March 2022

28 October 2021 | and repeat after me - "Help Yourself"

23 September 2021 | Warning - Contains strong language and explicit drug references

23 September 2021 | or Everything's Going to Pot

04 September 2021 | or Out of my league

27 August 2021 | or 'The Whine of the Ancient Mariner

16 August 2021 | Found in marina toilet, torn into squares and nailed to door.

06 August 2021 | or 'The Myth of Fingerprints'

Recent Blog Posts

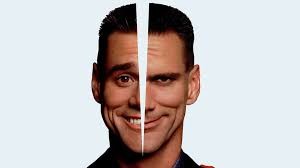

22 November 2023 | Here I am, stuck in the middle with you.

Clowns to the left of me, Jokers to the right

As a fully paid-up Guardianista, I am fully aware that blanket, stereotypic statements along the lines of:

Turkish Lessons

09 December 2017 | I’m not sure this is a good idea, but what the Hell – I’ll give it a go anyway.

I'm in the process of writing the sequel to my last book and was working on the bit about Istanbul when it struck me that it might make an interesting and slightly different blog post. It starts as a recommendation not to take Istanbul as representative of Turkey as a whole:

On the surface, it should be. After all, with a population of around fifteen million, it accounts for nearly twenty percent of Turkey's seventy eight million population. Compare that with Greater London's 8 ½ million accounting for just 13% of the UK's population.

No Brit would seriously contend that London was a representative microcosm of the whole UK (1). Few capital cities are (2). Most people, in most countries accept that such cities are special cases and are qualitatively different from most of the rest of the country. In fact, a lot of people actively resent what they see as the disproportionate influence their capital city and its resident movers and shakers have their lives, on the body politic and on other institutions of the country as a whole.

There is a school of thought that Brexit referendum result and the election of Donald Trump are manifestations of a polarisation of Western societies and that the political and philosophical middle ground is being lost to two extreme, diametrically opposed and aggressively conflicting world views. Well, compared to Turkey, the British are an homogenous mass of cloned sheep all called Brian.

Turkey's divisions go back to the founding of the republic in 1923 when Mustafa Kemal Atatürk raised the modern Republic of Turkey from the smouldering remains of the Ottoman Empire.

His aim was to establish a modern, secular, westernised, educated, emancipated society in a country primarily composed of conservative, Islamic, eastward-looking, predominantly illiterate, patriarchal peasants.

Well good luck with that. He obviously liked a challenge (3).

And he didn't sit on his arse twiddling his thumbs. In a few years he had transformed Turkish society. His reforms included the emancipation of women, the abolition or control of all Islamic institutions and the introduction of western legal codes and the western calendar. He set up a committee of linguists, educators and writers and told them to come up with a new latinate alphabet to replace the Arabic script in use at the time, and not to hang about. They did it in a year and it was implemented in three months. This, combined with his 'Campaign against ignorance' rapidly raised the literacy rate from around 10% to over 90%.

He wasn't all sweetness and light, though. People who get a lot done rarely are. Ali Kemal, one of his more influential critics, was intercepted by an ally of Atatürk who armed and incited a mob to lynch Kemal, a job they did most thoroughly with cudgels, stones and knives before hanging him from a tree with a rude notice pinned to his chest with a hunting knife (4).

Demonstrations of intent such as this, coupled with the fact that Atatürk was in charge of the army and so had most of the guns, swords, artillery, bombs and aeroplanes tended to discourage overt resistance to his reforms, which went ahead apace.

It's one thing to discourage overt opposition, but changing hearts and minds is another matter. A large proportion of the Turks did sign up wholeheartedly to Atatürk's ideas, but an equally large number found them anathema. Some of this opposition was philosophically and ideologically driven, but I'm sure the Imams and Madrassas weren't exactly thrilled with their loss of power and influence once they were effectively taken under government control.

The dividing lines between the two camps were not drawn only on religious and political grounds, but also on material and geographical ones. The secularists tended to be more liberal, better educated, wealthier, more influential and to live in the big cities and the western and southwestern coasts. Those in the other camp tended to be conservative, pious, poorly educated, impoverished, disenfranchised and they lived predominantly in the central and eastern parts of the country. They are also, probably, marginally greater in number than the secularists.

The secularists, though, have got the army on their side. Historically, should any uppity Islamist politician get within sniffing distance of power and so pose a threat to Atatürk's legacy, the army steps in with a gentle little coup as a reminder of who's actually in charge.(5)

All this elicits cognitive dissonance in the minds of wishy-washy liberals such as me. On the one hand the democratic will of the majority, especially the disadvantaged, should prevail. On the other hand the measures they want to implement are so fundamentally wrong and repressive that they should be avoided at almost all costs.

All of which brings echoes of the English Civil War as described by Sellar and Yeatman in '1066 and All That', where the Cavaliers were 'Wrong But Wromantic' whereas the roundheads were 'Right But Repulsive'. Who do you side with when the good guys do bad things and the bad guys do good things?

Turkey also serves as a model for possible developments in other western democracies where polarization seems to be occurring.

Conventional wisdom has it that power in liberal democracies goes to whoever wins the battle for the middle ground. This model is based on the premise that the electorate's attitudes on any matter (e.g. left vs right) are distributed in a bell curve. Very few have extreme left wing views and very few are extreme right-wingers. Most voters' views are bunched around the middle. This leads to more or less consensus politics where the majority of people think that government policy, if not exactly in tune with their thinking, is at least not too far from it. This encourages participation, engagement and debate. OK - it's not perfect but it's about the best we'll get in terms of peaceful co-existence.

A highly polarised electorate paints a very different picture. The distribution graph is no longer a dromedary's hump, but now looks like a couple of mountains with a valley between them. There is very little overlap in the middle. As a result it is pointless for a politician to court the middle ground. In practical terms, there isn't any. Instead, power now goes to whoever successfully panders to whichever is the bigger of the two humps which lie at the two extremes. This goes by the rather clumsy title of a majoritarian disctatorship.

Government policies will now be sorely resented by the nearly 50% of the population in the losing hump who will now, with considerable justification, feel voiceless, disenfranchised and run roughshod over by a government that treats them and their views and feelings with dismissive contempt. The winning side, meanwhile, stands a good chance of further inflaming the situation with arrogant crowing, taunting and metaphorically rubbing the losers' noses in it. The old virtues of graciousness in defeat and magnanimity in victory fade and die. This holds true whichever side wins.

Such polarisation is not an automatic precursor to civil strife but I suspect it is an important and necessary prerequisite. Perhaps one of the most important tasks currently facing liberal democracies is to address this polarisation starting with trying to determine its causes.

I'll start the ball rolling. Why do so many feel angry, frustrated and impotent when they have to suffer the consequences of the self-serving shenanigans of the political, financial and business classes. And remember, to misquote H.L. Mencken:

"To every complex problem there is an answer that is easy, neat, simple, plausible and wrong."

(1) Well, no Brit in his or her right mind anyway. (Which is by no means all of them)

(2) I know, I know - Ankara is the capital of Turkey. Istanbul's still the biggest city though.

(3) He also liked a drink and was reputed to have drunk a litre of raki every day of his adult life. That's around 350 units a week - makes me feel quite restrained. Mind you, he did die at 57 from chronic liver disease.

(4) One can justifiably question his methods, but I would also question his timing. If the deed had to be done, it would have been better twelve years earlier, Then Kemal wouldn't have sired Osman Johnson who in turn would not have sired Stanley Johnson. Which in turn means we wouldn't have had to suffer Boris.

(5) Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has played the long game very cleverly. The 2016 coup attempt failed.

On the surface, it should be. After all, with a population of around fifteen million, it accounts for nearly twenty percent of Turkey's seventy eight million population. Compare that with Greater London's 8 ½ million accounting for just 13% of the UK's population.

No Brit would seriously contend that London was a representative microcosm of the whole UK (1). Few capital cities are (2). Most people, in most countries accept that such cities are special cases and are qualitatively different from most of the rest of the country. In fact, a lot of people actively resent what they see as the disproportionate influence their capital city and its resident movers and shakers have their lives, on the body politic and on other institutions of the country as a whole.

There is a school of thought that Brexit referendum result and the election of Donald Trump are manifestations of a polarisation of Western societies and that the political and philosophical middle ground is being lost to two extreme, diametrically opposed and aggressively conflicting world views. Well, compared to Turkey, the British are an homogenous mass of cloned sheep all called Brian.

Turkey's divisions go back to the founding of the republic in 1923 when Mustafa Kemal Atatürk raised the modern Republic of Turkey from the smouldering remains of the Ottoman Empire.

His aim was to establish a modern, secular, westernised, educated, emancipated society in a country primarily composed of conservative, Islamic, eastward-looking, predominantly illiterate, patriarchal peasants.

Well good luck with that. He obviously liked a challenge (3).

And he didn't sit on his arse twiddling his thumbs. In a few years he had transformed Turkish society. His reforms included the emancipation of women, the abolition or control of all Islamic institutions and the introduction of western legal codes and the western calendar. He set up a committee of linguists, educators and writers and told them to come up with a new latinate alphabet to replace the Arabic script in use at the time, and not to hang about. They did it in a year and it was implemented in three months. This, combined with his 'Campaign against ignorance' rapidly raised the literacy rate from around 10% to over 90%.

He wasn't all sweetness and light, though. People who get a lot done rarely are. Ali Kemal, one of his more influential critics, was intercepted by an ally of Atatürk who armed and incited a mob to lynch Kemal, a job they did most thoroughly with cudgels, stones and knives before hanging him from a tree with a rude notice pinned to his chest with a hunting knife (4).

Demonstrations of intent such as this, coupled with the fact that Atatürk was in charge of the army and so had most of the guns, swords, artillery, bombs and aeroplanes tended to discourage overt resistance to his reforms, which went ahead apace.

It's one thing to discourage overt opposition, but changing hearts and minds is another matter. A large proportion of the Turks did sign up wholeheartedly to Atatürk's ideas, but an equally large number found them anathema. Some of this opposition was philosophically and ideologically driven, but I'm sure the Imams and Madrassas weren't exactly thrilled with their loss of power and influence once they were effectively taken under government control.

The dividing lines between the two camps were not drawn only on religious and political grounds, but also on material and geographical ones. The secularists tended to be more liberal, better educated, wealthier, more influential and to live in the big cities and the western and southwestern coasts. Those in the other camp tended to be conservative, pious, poorly educated, impoverished, disenfranchised and they lived predominantly in the central and eastern parts of the country. They are also, probably, marginally greater in number than the secularists.

The secularists, though, have got the army on their side. Historically, should any uppity Islamist politician get within sniffing distance of power and so pose a threat to Atatürk's legacy, the army steps in with a gentle little coup as a reminder of who's actually in charge.(5)

All this elicits cognitive dissonance in the minds of wishy-washy liberals such as me. On the one hand the democratic will of the majority, especially the disadvantaged, should prevail. On the other hand the measures they want to implement are so fundamentally wrong and repressive that they should be avoided at almost all costs.

All of which brings echoes of the English Civil War as described by Sellar and Yeatman in '1066 and All That', where the Cavaliers were 'Wrong But Wromantic' whereas the roundheads were 'Right But Repulsive'. Who do you side with when the good guys do bad things and the bad guys do good things?

Turkey also serves as a model for possible developments in other western democracies where polarization seems to be occurring.

Conventional wisdom has it that power in liberal democracies goes to whoever wins the battle for the middle ground. This model is based on the premise that the electorate's attitudes on any matter (e.g. left vs right) are distributed in a bell curve. Very few have extreme left wing views and very few are extreme right-wingers. Most voters' views are bunched around the middle. This leads to more or less consensus politics where the majority of people think that government policy, if not exactly in tune with their thinking, is at least not too far from it. This encourages participation, engagement and debate. OK - it's not perfect but it's about the best we'll get in terms of peaceful co-existence.

A highly polarised electorate paints a very different picture. The distribution graph is no longer a dromedary's hump, but now looks like a couple of mountains with a valley between them. There is very little overlap in the middle. As a result it is pointless for a politician to court the middle ground. In practical terms, there isn't any. Instead, power now goes to whoever successfully panders to whichever is the bigger of the two humps which lie at the two extremes. This goes by the rather clumsy title of a majoritarian disctatorship.

Government policies will now be sorely resented by the nearly 50% of the population in the losing hump who will now, with considerable justification, feel voiceless, disenfranchised and run roughshod over by a government that treats them and their views and feelings with dismissive contempt. The winning side, meanwhile, stands a good chance of further inflaming the situation with arrogant crowing, taunting and metaphorically rubbing the losers' noses in it. The old virtues of graciousness in defeat and magnanimity in victory fade and die. This holds true whichever side wins.

Such polarisation is not an automatic precursor to civil strife but I suspect it is an important and necessary prerequisite. Perhaps one of the most important tasks currently facing liberal democracies is to address this polarisation starting with trying to determine its causes.

I'll start the ball rolling. Why do so many feel angry, frustrated and impotent when they have to suffer the consequences of the self-serving shenanigans of the political, financial and business classes. And remember, to misquote H.L. Mencken:

"To every complex problem there is an answer that is easy, neat, simple, plausible and wrong."

(1) Well, no Brit in his or her right mind anyway. (Which is by no means all of them)

(2) I know, I know - Ankara is the capital of Turkey. Istanbul's still the biggest city though.

(3) He also liked a drink and was reputed to have drunk a litre of raki every day of his adult life. That's around 350 units a week - makes me feel quite restrained. Mind you, he did die at 57 from chronic liver disease.

(4) One can justifiably question his methods, but I would also question his timing. If the deed had to be done, it would have been better twelve years earlier, Then Kemal wouldn't have sired Osman Johnson who in turn would not have sired Stanley Johnson. Which in turn means we wouldn't have had to suffer Boris.

(5) Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has played the long game very cleverly. The 2016 coup attempt failed.

Comments

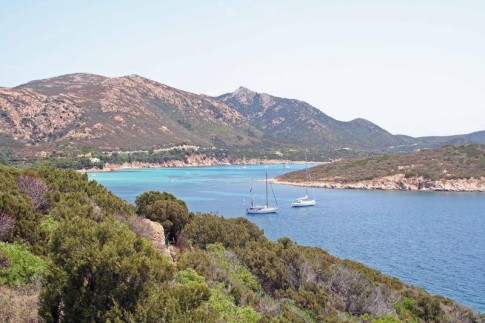

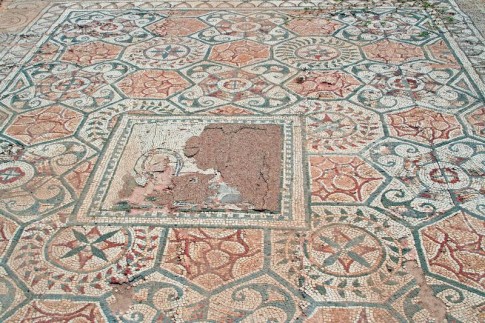

Birvidik's Photos - Birvidik (Main)

|

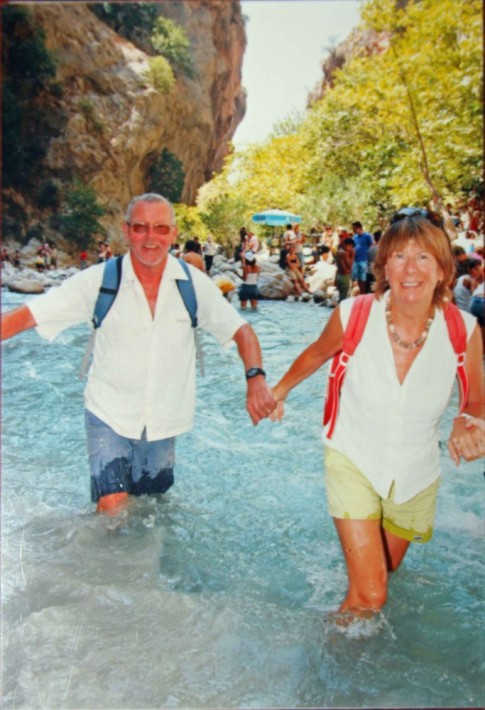

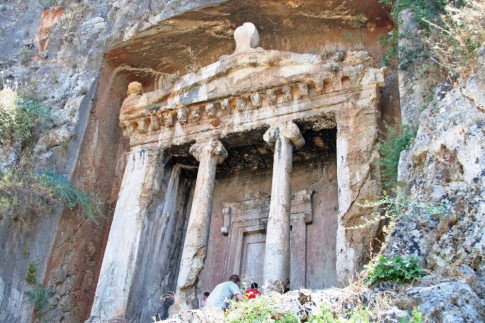

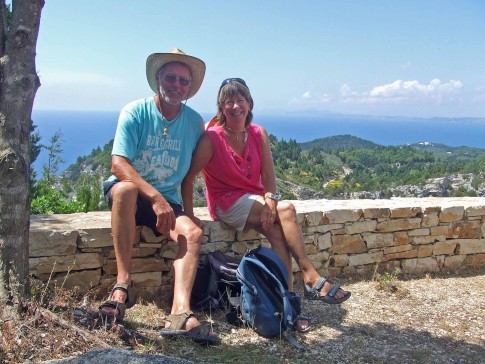

A selection of the myriad photographs taken over the 6 months in Lagos

37 Photos

Created 22 May 2007

|