Aloha

I�'ve been uncharacteristically quiet, I know. Until fairly recently, though, I haven�'t been quite sure this whole thing was going to work out, and I sure did not want to tell that story. Until fairly recently, I wasn�'t sure whether the voyaging dream was going to crash and burn, or my marriage was, or both. I�'ve been through the whole dissolution of marriage thing twice, and I was feeling some very unpleasant yet very familiar feelings of anxiety, self-blame, and failure. Any of you that know me will know that, starting right at the dock before I leave the harbor, I am always planning potential Plans B, C, D, etc.�-- sometimes going as high as F, depending on the number and probability of risks I�'m anticipating. So you may be surprised that, as far as the retirement Big Picture goes, I sailed from Hawai�'i without a Plan B. Once I got to the stage of �"ruh-roh, this may not be working�", I added �"shit, there is no Plan B�" to my picture of doom and gloom.

We left Ko Olina Marina on O�'ahu June 10, and arrived Taiohae, on the island of Nuku Hiva, in the Marquesas Islands on July 10. We had estimated a passage of 28- 30 days, so 30 days was pretty much on the money. Weather was favorable for the most part, winds were favorable for the most part. We would have made a faster passage if we hadn�'t had to shorten sail and come off the wind.

I say favorable for the most part. We got off to a flying start, making 8-9 knots the first several hours. We know better than to calculate an 1800-mile passage time based on a few hours sailing, but I�'ll admit to being tempted to believe it could be a 15-day passage instead of a 30-day passage. The lee of the Big Island reminded us that it could just as easily be a 40-day passage. We cheated our way through the light and variables, sixty miles offshore, using our trusty 55 horsepower Volvo Penta diesel engine to motor, before we came into the trades again, lofted sails, and resumed sailing.

I say �"trusty�" diesel, which it always has been. But it evinced a frustrating reluctance to start. Normally, you close the start battery breaker, push the �'on�' button, wait several seconds for a beep, push the �'start�' button, the engine immediately turns over and springs to life with a reassuring rumble. What it started doing instead, when you got to the �'start�' button step, was �... nothing. Well, there was a click. But no start. Or, no click, and no start. Most motors have a starting relay, which would produce such a click, but not the trusty Volvo Penta. Oh, no. The Volvo Penta sports a Mechanical Diesel Interface, which is, literally, a black box bolted to the side of the engine. Inside it is all sold state, so nothing to troubleshoot or fix. Luckily, though, there are wires and connectors on the black box, though nothing that was loose or corroded or otherwise something the handy boat owner could fix. However, as coincidence would have it, unbolting the MDI, and moving it around a little bit would somehow enable it to do more than just �'click�'. So, I did get the engine started, and we did motor our way through the lee of Hawai�'i, through the night, and through about 25% of my total fuel capacity.

So, problem solved, or at least we got it started that time. Later we will find out that this problem persists, with a couple of variations, and a new problem arises. But more about that when we get to Nuku Hiva�....

Once we cleared the Big Island, trades were 15-20 knots out of the north to northeast, and always enough north that we could stay to windward of the rhumb line to the Marquesas. We sailed close to the wind, but not pinched tight. Reasonably fast, reasonably comfortable. Days flowed smoothly into nights, the moon proceeded through it�'s phases, Mars rose in the east a little later each night, and the Southern Cross climbed higher and higher above the horizon.

We had a couple pretty lively runs, with the boat heeled over, and green water crashing over the bow, rolling aft over the deck, flooding the scuppers, and draining into the cockpit. One such wet patch resulted in water gushing over the deck, under the dodger, and into the companionway, cascading over the ladder and onto the deck grate in the cabin. This wet patch also occasioned a yell from Kirsten. This is the kind of yell that you would associate with an adrenaline rush, and which produces a sympathetic adrenaline rush. Stepping below to see what was going on, I saw water dripping from the seams in the overheads. Kirsten was a little wet and a little wide- eyed. She was standing in the cabin, next to the mast, arms extended overhead, hands on the ceiling panels. She sputtered something about water flooding from the overhead. I couldn�'t really quite believe this.

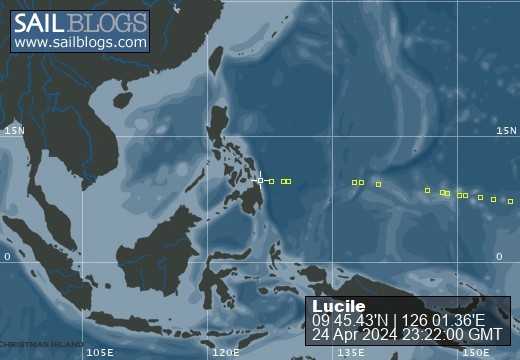

Lucile has always been a dry boat, very comfy as we travelled the Pacific Northwest, Hawai�'i to Alaska, Alaska to B.C. and Washington, back home to Maui. All kinds of weather, a lot of it wet, all kinds of seas, a lot of them as big as what we were seeing on this passage, and still pretty dry inside. Of course, a governing principle of boating is that you must keep the outside water outside. This interior waterfall could be quite significant.

Since I sometimes need the evidence of my own senses to believe something I can�'t or don�'t want to believe, the universe graced me with the following, which took place over about two seconds, maybe as long as three seconds, but which made a truly profound and lasting impression, notwithstanding it�'s relatively short presentation. First I heard what might sound like a load of plywood (4 x 8�', stacked waist high), dropped from a height about ten feet�--heard as if it were dropped on the floor which you were right under. That was the bow smacking into a wave, probably a pretty big wave, probably, based on what I�'d been seeing, about six to eight feet high. I�'d been hearing this noise, off and on, for a while (though from further aft, in the cockpit). Then I heard what sounded like someone in that malevolent crane had just dumped a backyard swimming pool�'s worth of water on the deck, water rushing fore to aft. Next I saw quite an interesting display of water fall. The ceiling panels are padded rectangles, primarily designed to hide the ugly part of the roof over your head; in Lucile�'s case, the underside of the fiberglass deck. The gaps in the panels are covered with wood trim. What I saw was a rectangular array of water falls, water cascading out from between the ceiling panels in the forward part of the main cabin, and the aft part of the vee-berth, or forward compartment. I saw Kirsten get drenched. I now believed.

I told Kirsten the waterfall, though uncomfortable, was not a cause for immediate concern, the ingress was well within the capacity of our bilge pump, and that I would take a look topside to see if I could figure out where it was ingressing.

Which I did. After inspecting the cabin, vee-berth, and forward head, I had a theory, which, going topside and taking a look at the location of the ventilator for the forward head, became convinced that was the culprit. I had two suspects in mind, the mast boot and the deck ventilator. When we re-rigged, I wedged the mast at the partners and installed a new mast boot, and I�'m always quick to suspect my own workmanship when problems surface, but the mast itself was dry where it extended through the partners and deck into the cabin. That pretty much left the ventilator. The ventilator is a hole deliberately cut into the deck, with a stainless steel cover on deck, and a little plate with a rubber gasket, which you can twist open or closed from inside the head. I double-checked that it was screwed tight, which meant only that I could not turn the knob in the overhead of the head any further in the �'close�' direction, but I remained convinced that was the source of our flooding. (This was later confirmed at Taiohae Bay, where I discovered the plate or disk with the gasket had broken loose from the threaded rod that the knob turned, and no amount of knob turning would seat the gasket and seal out the water. So I pop riveted the disk back in place, screwed it down tight, very tight, and put the cover back on. No leaks since. Or at least, not through the vent.)

So, problem solved, or at least significantly reduced. Later we will find out that there are many other leaks. But more about that when we get to Pago Pago.

Then we hit the doldrums. I�'ve read lots of stories, heard lots of stories, about the doldrums. But, really, our experience was neither as dramatic, or as boring, as I had anticipated. We had light winds sporadically, and no wind sporadically. We got to dousing our sails completely, and catching up on sleep when there was no wind. When the breezes freshened, up went the sails, and we ghosted along as best we could until they died again. It sounds easy and relaxing, and in a way it was. But it was also extremely frustrating, trying to get anything out of a puff of air, listening to the sails and rigging flog and flap with the roll of the boat, and finally giving up, in hopes of better sailing later. A good day�'s passage for us is 125+ miles, but we were happy to get 50 or 60 in the doldrums. There was one exciting part of the doldrums, and that would be the rain squalls. One evening in particular, I saw dark looming on the horizon, black against twilight. If I weren�'t in the middle of the ocean, I would swear we were approaching land. I turned on the radar to check. There was a radar return, all right, but it wasn�'t land. It was rain. We closed and snugged up hatches, and hunkered down, waiting to get wet.

Boy did we get wet. I�'ve been in some good downpours before, but nothing like this. I had to cover my nose and mouth with my hand in order to breathe. I had to shield my eyes to see. The rain turned the surface of the ocean silver white. Rain splashed up from the surface of the ocean, almost deck high. It rained so hard, water was gushing off the dodger, and spurting out the scuppers in the toe rail. It rained so hard, the only sound you could hear was the rain hitting the boat and the ocean. It was amazing. And then, within the hour, it was done.

Overall, I�'d say the doldrums were pretty easy. We lucked out in that they only extended from about 6 degrees north, to about 3 ½ degrees north, about 150 miles, and after four or five days of doldrums, we were back in the trades, the southern trades, and back to 100-125 miles per day, until one fresh breezy morning.

I came up on deck for my watch. My habit is to take a comfortable seat, and take a look around. I was sitting in the cockpit scanning my boat and my surroundings, letting my eyes stop and focus wherever they wanted to. I looked at the sea surface, it�'s color and shape, the number of swells, and at what stage of development, the shape and waves and their period, the degree of whitecapping. I looked at the sky, how much cloud cover, what kind of clouds, what direction the clouds are moving at different elevations, are they making rain, how dark are the dark patches, and how big are they. I look at the sail trim, the shape of the sails, are they balanced, are all lines running fair. I look at my standing rigging, how are leeward shrouds keeping tension as the boat heels. Looking up at the lower shrouds and spreaders, my eyes stopped. Something didn�'t look right. My gaze lingering at the tangs and toggles, my eyes decided that one of the tangs, where the port lower forward shroud attaches to the mast, was broken. That got my attention, and the rest of my brain engaged with my eyes and focused on that little problem.

I alerted Kirsten, and we got to work taking the load off the mast and rigging.

Lucile�'s mast is 65 feet long, and several hundred pounds, maybe about 600 pounds. Heavy enough that when we re-rigged this past summer, we used a crane to lift the mast off the boat. It is the mast�'s job to hold aloft the 408 square feet of main sail and the 499 square feet of head sail. The force of the wind on the sails is substantial, thousands and thousands of pounds. It is the rigging�'s job to hold the mast and sails up, preventing the mast from bending, buckling and otherwise breaking and crashing onto the deck, possibly injuring, or killing, crew or passengers; possibly damaging, or holing, the hull; possibly even sinking the boat. The stays and shrouds on the mast are like the guy wires on a telephone pole or radio antenna, holding them upright and preventing them from buckling. The four lower shrouds surround the lower part of the mast. They attach to chainplates at deck level, and attach to the mast just below the lower spreaders, about 20 feet up. If you were building a 10-person human pyramid, you�'d put your four big, beefy guys on the bottom row. The lower shrouds are the four big, beefy guys on the bottom row, and one of my big, beefy guys just broke his wrist. The trick is to get the cheerleaders down from the top of the pyramid safely, before the one guy gives out and the whole pyramid comes tumbling down.

Sailing, this meant reducing the square footage of sails up, so we reefed the main sail, and partially furled the genoa. Then we sweated and agonized. Knowing the wire rope shrouds were sized a bit beefier than the design specification, and knowing the design was fairly conservative to start with, I was reasonably confident that we would be able to keep the rig up. This was important for reaching our destination, hell, any destination, as there is not sufficient fuel on board to cover the remaining distance to our destination.

We spent most of our time with the wind coming over the right side of the boat, on a starboard tack, headed roughly south southeast, with the wind roughly east. We still needed a fair amount of easting to get to the Marquesas, but we couldn�'t sail as close to the wind reefed as we could with the full main. In other words, we were limited in how much east of south we could point. This raised the question of whether it made sense to come off the wind a bit, and sail almost due south to Tahiti. But Tahiti was several hundred miles further than the Marquesas Islands, so I decided to shorten the exposure to risk by taking the shorter route, even if it were only by a couple of days. In retrospect, it probably would have been faster to Tahiti, because I had to tack a couple of times to get to the Marquesas. When I tacked, I had to turn over 120 degrees, so I would end up heading south southwest, and losing easting in the process.

Fortunately, conditions were largely favorable for an extended tack, and, to make a long story short, we make landfall in Taiohae Bay, on the island of Nuku Hiva.

Landfall was not completely without incident, though, and this blog hasn�'t touched on the emotional toll exacted by this passage. So I guess I�'ll have to write more, later.

In the meantime, you will hopefully be as happy as I am to know that the watermaker works, and does not leak.

Haole Makahiki Hou!

We left Ko Olina Marina on O�'ahu June 10, and arrived Taiohae, on the island of Nuku Hiva, in the Marquesas Islands on July 10. We had estimated a passage of 28- 30 days, so 30 days was pretty much on the money. Weather was favorable for the most part, winds were favorable for the most part. We would have made a faster passage if we hadn�'t had to shorten sail and come off the wind.

I say favorable for the most part. We got off to a flying start, making 8-9 knots the first several hours. We know better than to calculate an 1800-mile passage time based on a few hours sailing, but I�'ll admit to being tempted to believe it could be a 15-day passage instead of a 30-day passage. The lee of the Big Island reminded us that it could just as easily be a 40-day passage. We cheated our way through the light and variables, sixty miles offshore, using our trusty 55 horsepower Volvo Penta diesel engine to motor, before we came into the trades again, lofted sails, and resumed sailing.

I say �"trusty�" diesel, which it always has been. But it evinced a frustrating reluctance to start. Normally, you close the start battery breaker, push the �'on�' button, wait several seconds for a beep, push the �'start�' button, the engine immediately turns over and springs to life with a reassuring rumble. What it started doing instead, when you got to the �'start�' button step, was �... nothing. Well, there was a click. But no start. Or, no click, and no start. Most motors have a starting relay, which would produce such a click, but not the trusty Volvo Penta. Oh, no. The Volvo Penta sports a Mechanical Diesel Interface, which is, literally, a black box bolted to the side of the engine. Inside it is all sold state, so nothing to troubleshoot or fix. Luckily, though, there are wires and connectors on the black box, though nothing that was loose or corroded or otherwise something the handy boat owner could fix. However, as coincidence would have it, unbolting the MDI, and moving it around a little bit would somehow enable it to do more than just �'click�'. So, I did get the engine started, and we did motor our way through the lee of Hawai�'i, through the night, and through about 25% of my total fuel capacity.

So, problem solved, or at least we got it started that time. Later we will find out that this problem persists, with a couple of variations, and a new problem arises. But more about that when we get to Nuku Hiva�....

Once we cleared the Big Island, trades were 15-20 knots out of the north to northeast, and always enough north that we could stay to windward of the rhumb line to the Marquesas. We sailed close to the wind, but not pinched tight. Reasonably fast, reasonably comfortable. Days flowed smoothly into nights, the moon proceeded through it�'s phases, Mars rose in the east a little later each night, and the Southern Cross climbed higher and higher above the horizon.

We had a couple pretty lively runs, with the boat heeled over, and green water crashing over the bow, rolling aft over the deck, flooding the scuppers, and draining into the cockpit. One such wet patch resulted in water gushing over the deck, under the dodger, and into the companionway, cascading over the ladder and onto the deck grate in the cabin. This wet patch also occasioned a yell from Kirsten. This is the kind of yell that you would associate with an adrenaline rush, and which produces a sympathetic adrenaline rush. Stepping below to see what was going on, I saw water dripping from the seams in the overheads. Kirsten was a little wet and a little wide- eyed. She was standing in the cabin, next to the mast, arms extended overhead, hands on the ceiling panels. She sputtered something about water flooding from the overhead. I couldn�'t really quite believe this.

Lucile has always been a dry boat, very comfy as we travelled the Pacific Northwest, Hawai�'i to Alaska, Alaska to B.C. and Washington, back home to Maui. All kinds of weather, a lot of it wet, all kinds of seas, a lot of them as big as what we were seeing on this passage, and still pretty dry inside. Of course, a governing principle of boating is that you must keep the outside water outside. This interior waterfall could be quite significant.

Since I sometimes need the evidence of my own senses to believe something I can�'t or don�'t want to believe, the universe graced me with the following, which took place over about two seconds, maybe as long as three seconds, but which made a truly profound and lasting impression, notwithstanding it�'s relatively short presentation. First I heard what might sound like a load of plywood (4 x 8�', stacked waist high), dropped from a height about ten feet�--heard as if it were dropped on the floor which you were right under. That was the bow smacking into a wave, probably a pretty big wave, probably, based on what I�'d been seeing, about six to eight feet high. I�'d been hearing this noise, off and on, for a while (though from further aft, in the cockpit). Then I heard what sounded like someone in that malevolent crane had just dumped a backyard swimming pool�'s worth of water on the deck, water rushing fore to aft. Next I saw quite an interesting display of water fall. The ceiling panels are padded rectangles, primarily designed to hide the ugly part of the roof over your head; in Lucile�'s case, the underside of the fiberglass deck. The gaps in the panels are covered with wood trim. What I saw was a rectangular array of water falls, water cascading out from between the ceiling panels in the forward part of the main cabin, and the aft part of the vee-berth, or forward compartment. I saw Kirsten get drenched. I now believed.

I told Kirsten the waterfall, though uncomfortable, was not a cause for immediate concern, the ingress was well within the capacity of our bilge pump, and that I would take a look topside to see if I could figure out where it was ingressing.

Which I did. After inspecting the cabin, vee-berth, and forward head, I had a theory, which, going topside and taking a look at the location of the ventilator for the forward head, became convinced that was the culprit. I had two suspects in mind, the mast boot and the deck ventilator. When we re-rigged, I wedged the mast at the partners and installed a new mast boot, and I�'m always quick to suspect my own workmanship when problems surface, but the mast itself was dry where it extended through the partners and deck into the cabin. That pretty much left the ventilator. The ventilator is a hole deliberately cut into the deck, with a stainless steel cover on deck, and a little plate with a rubber gasket, which you can twist open or closed from inside the head. I double-checked that it was screwed tight, which meant only that I could not turn the knob in the overhead of the head any further in the �'close�' direction, but I remained convinced that was the source of our flooding. (This was later confirmed at Taiohae Bay, where I discovered the plate or disk with the gasket had broken loose from the threaded rod that the knob turned, and no amount of knob turning would seat the gasket and seal out the water. So I pop riveted the disk back in place, screwed it down tight, very tight, and put the cover back on. No leaks since. Or at least, not through the vent.)

So, problem solved, or at least significantly reduced. Later we will find out that there are many other leaks. But more about that when we get to Pago Pago.

Then we hit the doldrums. I�'ve read lots of stories, heard lots of stories, about the doldrums. But, really, our experience was neither as dramatic, or as boring, as I had anticipated. We had light winds sporadically, and no wind sporadically. We got to dousing our sails completely, and catching up on sleep when there was no wind. When the breezes freshened, up went the sails, and we ghosted along as best we could until they died again. It sounds easy and relaxing, and in a way it was. But it was also extremely frustrating, trying to get anything out of a puff of air, listening to the sails and rigging flog and flap with the roll of the boat, and finally giving up, in hopes of better sailing later. A good day�'s passage for us is 125+ miles, but we were happy to get 50 or 60 in the doldrums. There was one exciting part of the doldrums, and that would be the rain squalls. One evening in particular, I saw dark looming on the horizon, black against twilight. If I weren�'t in the middle of the ocean, I would swear we were approaching land. I turned on the radar to check. There was a radar return, all right, but it wasn�'t land. It was rain. We closed and snugged up hatches, and hunkered down, waiting to get wet.

Boy did we get wet. I�'ve been in some good downpours before, but nothing like this. I had to cover my nose and mouth with my hand in order to breathe. I had to shield my eyes to see. The rain turned the surface of the ocean silver white. Rain splashed up from the surface of the ocean, almost deck high. It rained so hard, water was gushing off the dodger, and spurting out the scuppers in the toe rail. It rained so hard, the only sound you could hear was the rain hitting the boat and the ocean. It was amazing. And then, within the hour, it was done.

Overall, I�'d say the doldrums were pretty easy. We lucked out in that they only extended from about 6 degrees north, to about 3 ½ degrees north, about 150 miles, and after four or five days of doldrums, we were back in the trades, the southern trades, and back to 100-125 miles per day, until one fresh breezy morning.

I came up on deck for my watch. My habit is to take a comfortable seat, and take a look around. I was sitting in the cockpit scanning my boat and my surroundings, letting my eyes stop and focus wherever they wanted to. I looked at the sea surface, it�'s color and shape, the number of swells, and at what stage of development, the shape and waves and their period, the degree of whitecapping. I looked at the sky, how much cloud cover, what kind of clouds, what direction the clouds are moving at different elevations, are they making rain, how dark are the dark patches, and how big are they. I look at the sail trim, the shape of the sails, are they balanced, are all lines running fair. I look at my standing rigging, how are leeward shrouds keeping tension as the boat heels. Looking up at the lower shrouds and spreaders, my eyes stopped. Something didn�'t look right. My gaze lingering at the tangs and toggles, my eyes decided that one of the tangs, where the port lower forward shroud attaches to the mast, was broken. That got my attention, and the rest of my brain engaged with my eyes and focused on that little problem.

I alerted Kirsten, and we got to work taking the load off the mast and rigging.

Lucile�'s mast is 65 feet long, and several hundred pounds, maybe about 600 pounds. Heavy enough that when we re-rigged this past summer, we used a crane to lift the mast off the boat. It is the mast�'s job to hold aloft the 408 square feet of main sail and the 499 square feet of head sail. The force of the wind on the sails is substantial, thousands and thousands of pounds. It is the rigging�'s job to hold the mast and sails up, preventing the mast from bending, buckling and otherwise breaking and crashing onto the deck, possibly injuring, or killing, crew or passengers; possibly damaging, or holing, the hull; possibly even sinking the boat. The stays and shrouds on the mast are like the guy wires on a telephone pole or radio antenna, holding them upright and preventing them from buckling. The four lower shrouds surround the lower part of the mast. They attach to chainplates at deck level, and attach to the mast just below the lower spreaders, about 20 feet up. If you were building a 10-person human pyramid, you�'d put your four big, beefy guys on the bottom row. The lower shrouds are the four big, beefy guys on the bottom row, and one of my big, beefy guys just broke his wrist. The trick is to get the cheerleaders down from the top of the pyramid safely, before the one guy gives out and the whole pyramid comes tumbling down.

Sailing, this meant reducing the square footage of sails up, so we reefed the main sail, and partially furled the genoa. Then we sweated and agonized. Knowing the wire rope shrouds were sized a bit beefier than the design specification, and knowing the design was fairly conservative to start with, I was reasonably confident that we would be able to keep the rig up. This was important for reaching our destination, hell, any destination, as there is not sufficient fuel on board to cover the remaining distance to our destination.

We spent most of our time with the wind coming over the right side of the boat, on a starboard tack, headed roughly south southeast, with the wind roughly east. We still needed a fair amount of easting to get to the Marquesas, but we couldn�'t sail as close to the wind reefed as we could with the full main. In other words, we were limited in how much east of south we could point. This raised the question of whether it made sense to come off the wind a bit, and sail almost due south to Tahiti. But Tahiti was several hundred miles further than the Marquesas Islands, so I decided to shorten the exposure to risk by taking the shorter route, even if it were only by a couple of days. In retrospect, it probably would have been faster to Tahiti, because I had to tack a couple of times to get to the Marquesas. When I tacked, I had to turn over 120 degrees, so I would end up heading south southwest, and losing easting in the process.

Fortunately, conditions were largely favorable for an extended tack, and, to make a long story short, we make landfall in Taiohae Bay, on the island of Nuku Hiva.

Landfall was not completely without incident, though, and this blog hasn�'t touched on the emotional toll exacted by this passage. So I guess I�'ll have to write more, later.

In the meantime, you will hopefully be as happy as I am to know that the watermaker works, and does not leak.

Haole Makahiki Hou!

Comments