Asylum

22 June 2019 | Straits Quay Marina, Penang, Malaysia

17 July 2016 | Penang, Malaysia

20 February 2016 | Penang, Malaysia

02 October 2015 | Thailand

11 April 2015 | Krabi Boat Lagoon Marina, Thailand

25 December 2014 | Langkawi, Malaysia

04 June 2014 | Philippines

07 January 2014 | Brookeville, MD

04 July 2013 | Subic Bay Yacht Club, Philippines

31 October 2012 | Palau

02 December 2011 | Hermit Islands, Papua New Guinea

08 November 2011 | Maryland, USA

15 May 2011 | Kavieng, New Ireland, PNG

26 April 2011 | Kavieng, New Ireland

26 March 2011 | Kokopo, New Britain, Papua New Guinea

16 March 2011 | Kokopo, New Britain, Papua New Guinea

12 February 2011 | From Peava again

05 February 2011 | Solomon Islands

01 December 2010 | From Lola Island, VonaVona Lagoon, Solomon Islands

30 November 2010 | Peava, Nggatoke, Solomon Islands

Inmate Update #10 part 1: Bonaire to Aruba, via Haiti and other parts north

15 July 2002 | Aruba, Netherlands Antilles

Once again I begin this by saying I can't believe how long it's been since the last one--more than 6 months this time. And except for the last couple, it's been a pretty tame 6 months. But these last 2½ have been real doozies! Read on.

When last we left you in late November, we'd just arrived in Bonaire, the "B" and eastern-most of the ABC islands (Aruba, Bonaire, and Curacao), known as the Netherlands Antilles. After a couple of weeks there--long enough to get our advanced dive certification and log a bunch more dives--we headed west to Curacao, where Asylum was hauled from the water on a marine railway and we were hauled from the islands on a 737. Fast-forwarding through the next few weeks, we returned to the boat, with its shiny new bottom and fresh red stripes, in late January, waited for a good day to slog back east to Bonaire, and got back there in early February. Curacao is ok, but not a good place for cruiser/divers to hang out for any long period of time. It's very built up, has its own version of a beltway, terrible traffic, and a smoke-belching oil refinery. Bonaire, on the other hand, has not a single traffic light on the island, you can walk everywhere you need to go, and can dive off the side of your boat! There was no question that this was where we were going to hang out for a while and figure out our plan for the rest of the year. (OK, so the diesel was 1/3 the cost in Curacao, but we're a sailboat, right?)

When we decided late last year not to go thru the Panama Canal early this year, it meant we had to come up with something to do with ourselves till the next transit window--or until we changed our minds again. (Cruisers are nothing if not flexible. Most of us use jello as the metaphor for the consistency of our "plans," as in: "still liquid" or "firming up" or "not set yet," or "melted.") As I think I've mentioned before, while it may seem that cruisers are free to come and go whenever and to wherever they please, this is only what the magazines tell you. In fact, it's not at all true. We are slaves to and victims of annual weather patterns and opportunistic "weather windows." Some of these windows only open once a year, so if you dawdle, hesitate, or otherwise manage to miss them, you wait a year. That's where we were in early Feb upon returning to Bonaire: diving a lot, and deciding what to do until we decided what to do.

A seed planted upon our arrival in Bonaire in November already was starting to germinate. We had met a couple on a boat called Runaway when we got there. They had recently completed a 7-year circumnavigation, he at the age of 72 and she 70! They were quite remarkable, and Asylum and Runaway clicked immediately. They were also avid divers, putting us to shame (or at least me) the way they could haul themselves up into their dinghy after a dive. They had mentioned their desire/plan to go to Cuba in April. Why don't we come with them? The fact is, we'd wanted to go to Cuba. Supposedly fabulous cruising, especially along the south coast, wonderful people, and still for all kinds of reasons, a "unique" place to visit in the Caribbean. Seed planted.

We mulled. Looked at charts. Talked it over with ourselves and with them. The trip made sense for Runaway: they were planning to head for the Bahamas. But we were still "planning" to head south (eventually), and Cuba was north. A long way north as far as a sailboat is concerned. And not only was Cuba north, it was northwest, which was good for getting up there but not good for getting back. So we continued to ponder, study the charts, the pilot charts, the cruising guides, and others' notes and experiences. It seemed to be do-able, and, well, what else did we have to do? And so, with part gulp and part what-the-hell, we decided to go to Cuba with Runaway in April.

When they were in the States in March, they gathered cruising guides and charts for both of us, but most importantly, obtained a license from a Jewish humanitarian organization in Boston with a "mission" in Havana, that made our visit sponsored and "legal." (There's a lot of confusion about if/how Americans can go to Cuba. The bottom line is that Americans can go to Cuba, but if you're not sponsored or there with the permission of the US gov't, you can't spend any money. Among American cruisers, the rule of thumb is "find a Canadian and go with them.") They also brought back with them a large supply of OTC medicines, toothpaste and toothbrushes, vitamins, etc., for us to deliver to the mission. To all of that we added soaps and school supplies--all reportedly much-needed items for the average Cuban. Not only that, but a local priest they met in Boston also gathered a huge box of children's clothes for us to take to Ile a Vache, Haiti, one of the planned stops on the way to Cuba. We were ready to go.

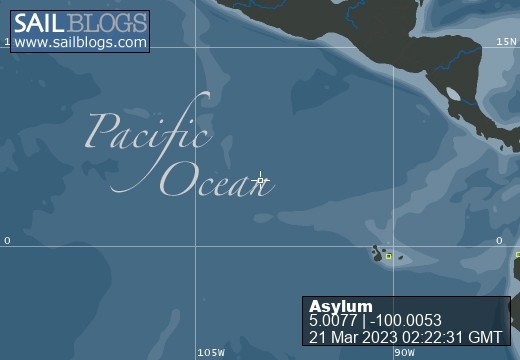

Our planned route (get out your maps!): Bonaire to Curacao (a short day sail). Curacao to Ile a Vache, a small island off the SW coast of Haiti's main island (3 days). Ile a Vache to Jamaica (about 2 days). Jamaica to one of the Cayman Islands (24 hours). Caymans to Cayo Largo, an island on the south Coast of Cuba (24 hours), where we would clear in. We were pleased to be traveling with Runaway, seriously experienced cruisers who said they simply "didn't do" bad passages and just waited for weather, as long as it took to get favorable conditions. So on April 7 we left Bonaire for Curacao, where we planned to stop only a day or two, long enough to do some add'l provisioning and buy the extra soap and school supplies. But what we thought was going to be a good window wasn't. The weather piped up north of us, right where we were headed, and we had to wait a week for the seas to come back down.

They did, and on April 13 we were ready to go. Pulled up the anchor and were on our way out of the anchorage behind Runaway when they turned around and headed back in. The wind-speed indicator on the top of their mast was stuck and wasn't doing any indicating so they matter-of-factly re-anchored and sent 73-yr old Dick smartly up the mast to unstick it. We circled slowly for about 45 minutes while they did their thing and then off we went on our 3-day trip, pretty much straight north, to Ile a Vache.

Conditions were great, the sailing was good, and we were off to a promising start. We had decided to try the quarter berth as our passage berth this time rather than sleeping in the main salon as we had on past passages. We normally sleep in the V-berth (at the bow of the boat), but underway there's simply too much motion up there so we move to the center, or this time, farther aft, where the boat's motion is less. We were on a 3-day starboard tack (sails on the port side), so as the boat heeled, we rolled into the port bulkhead and wedged ourselves in with a pillow. It was a comfortable little nest for the 3-4 hours of sleep we traded off getting. We also seemed to find our stride on a watch schedule this time. Before, we'd been kind of loose about who slept when, but all the books say to find one that works for you and stick to it. We arranged things by our natural rhythms--me the night owl, Jim the morning person--and managed to get about 3 hours of sleep on each of 2 night watches, with cat-naps during the day. It worked pretty well, tho the books also say that passages of 1-3 days are the hardest because it takes a good 3 days to really get into the watch rhythm.

This was a great 3-day passage. Caught a tuna. Visited by a pod of high-spirited and high jumping dolphins. Intensely thick stars (tho no moon). Wind picked up the 3rd night, it got kinda lumpy, and we had to mess with sails a few times, but it wasn't too bad. And then on the morning of the 16th we could see the island of Hispaniola (Haiti on the left, the Dominican Republic on the right) on the horizon, with our destination, the little island of Ile a Vache (Island of the Cow) just ahead. Everywhere around the coast were fishermen, some in leaky little dugout canoes that we wouldn't take out on a flat lake on a calm day. Others were in amazing, hand-built wooden sail boats, with what looked like bedsheets for sails. And everywhere, reminiscent of the crab and lobster pots in the Chesapeake and Maine, were fish traps! Unlike the bright colored floats in the north, these were often clear plastic coke bottles that you couldn't see until you were on top of them, about to wrap your prop with their lines. But for the sun and one of us on the bow yelling to throw the engine into neutral any number of times, Jim (!!) would have been diving on the prop...

Overall our passage lumps were pretty minor: the staysail halyard was almost chafed thru (an easy cut and fix); the stern running light flickered on and off a few times (Jim checks wiring); a hank broke on the staysail (put a new one on); the mast rivets for the port-side lazy jacks broke--lazy jacks are a string and pulley system that contains the mainsail when it's reefed and lowered--(Jim goes up the mast and replaces the rivets). But we had a few days to work on these.

Ile a Vache was a study in contrasts. On the one hand there was a lovely resort hotel. A French couple, Didier and Francoise, had spent the past 5 years building this hotel/resort with a small marina operation that had only recently opened and was in its fledgling stage of operation. The setting was idyllic: the hotel perched on a hill overlooking palm trees, bougainvillea, beaches, and off in the distance, beautiful Hispaniola. But the rest of the island of Ile a Vache is National Geographic territory: no roads, no running water, no electricity; women carrying enormous bundles (often in huge aluminum tubs) on their heads; thatch roof huts; little naked kids running around, playing with sticks or stuff they find on the beach. From the moment of our arrival we had people coming to our boat in ratty, leaky little dugout canoes (literally dug out), usually paddling with a piece of wood--rarely a real paddle, and bailing constantly--to ask for work, to sell or trade something, or just to ask for something. Our visitors were almost always young men and little boys, only once were there 2 young girls in the canoe. They spoke Creole mostly, some French, and a few knew a few words of English (especially, "What is your name?" and "Give me something!"). Sometimes there were 3 or 4 of these little boats full of kids hanging off the side of Asylum, banging into each other and to us. Some came trying to sell little limes ("citrons," about the diameter of a quarter); others may have a tomato or an egg or a scrawny little fish, or a shell they proffered. Interestingly, lots of them asked for "un stylo" (a pen) in trade. We had our stash of school supplies, including pens and pencils, for Cuba so broke into that as we accumulated more limes than we could use in a year. Some asked for "a bon bon" (a piece of candy), a few wanted dictionaries or books. One little boy wanted a red T-shirt. We didn't have any red ones, but pulled out a pile we were willing let go and let him pick the next best thing to red. After a while, these relentless visits wear you down, and we would spend more and more time below, out of sight, to avoid having to deal with them. "Urchins at 2 o'clock!" one of us would alert the other when we saw a paddler approach. Sometimes they'd give up and go away if you didn't respond to their calls of "Hello. Hello. Hello." But some could out-wait you, just hanging off the side, knowing you were in there and eventually would have to come up. For these we mastered in French, "We're very busy now," "Nothing today, thank you," "Good-bye" or, eventually, a firm but polite version of "Get lost!"

We did hire a couple of the young men to do some boat work for us. One of the things we were going to do in Bonaire, but successfully put off doing, was polish all the stainless on the boat--a necessary but tedious task. We had learned that the going wages were $3 - 5 a day, so this seemed like a win-win situation to us: these guys got the work they needed and we didn't have to polish the stainless! The two we hired worked very diligently and did a great job. They also washed and waxed the hull--another job we'd put off doing in Bonaire. Sometimes procrastination pays!

Thursday was market day in the island's main "city" of Madame Bernard. The only way to get there from where we were was by dinghy, by foot, or on horseback. The walk, we were told, was a good 2 hours over muddy trails, and we didn't have a horse... So with a young man from the village, Wagner, as our local guide, we set out in the dinghy for the 20 minute ride along the impressive north coast of Ile a Vache. Many vendors come from the main island, off to our left, in small, locally-built sail boats. The passage between the 2 islands was full of them that morning, and many of these boats were full to the gunwales with people. I use the term "city" because they do, but that's a stretch. This is one rough place. No streets, no sidewalks, no power. It had rained torrentially the last couple of days (the source of all fresh water on the island) and the market area was a flooded mud swamp. Horses were tethered everywhere. Most of the people were barefoot. We visited an orphanage, run by a French Canadian nun, where we delivered the bags of clothes that Runaway had brought from Boston. Most of the kids there were not merely orphans, but also had medical problems (we saw several with CP). We also visited an elementary school, where all the kids were in brown bottom (short or skirts) and bright yellow shirts. ALL of the girls also were festooned with bright yellow ribbons in their hair. About half were barefoot. It costs a family anywhere from $20 to $40 a year to send 1 child to elementary school. Many families with multiple children (and they all seem to have a LOT!) can only send 1 kid for 1 year, then maybe another kid for the next year, or maybe not anybody. Most of the people we talked to in the village near where we were anchored had only been to school fleetingly, and in fact money to go to school was one of the things they often asked for.

Despite the steady stream of "visitors" to the boat, all of them peering in with great curiosity, we were told that security was no problem. "No need to lock the dinghy at night," said fellow cruisers who'd been there a while. So imagine our surprise when Jim pokes his head out to survey the scene early on our 4th morning there and sees the painter to Runaway's dinghy hanging limp and dinghy-less at the side of their boat. Continuing to survey the scene he sees their dink on the beach nearby, sans engine and gas tank (and, we learned later, a tool box they kept in there). Ohmygoodness did this generate a buzz and flurry of activity! The police from the main island were brought in. The village chief got involved. The villagers were angry, not only because it ruined their good name but more importantly, we were told, that having the police snooping around interfered with their rather active drug activities. The hotel owners (who provide virtually all of the employment to the village) basically said to the locals, "Until the engine is found and returned, don't even think about bothering these boats." We were amazed at how quiet things suddenly got in the anchorage. No visitors. No little voices calling "Hello. Hello. Hello. Give me something." But everybody in the village was pretty sure they knew who did it and everybody was looking for the guy. Cautiously optimistic that they might get the engine back (when this happened a few years ago, the engine was recovered), Runaway nonetheless started calling Jamaica and Grand Cayman to see if/where they could get a new engine. In the meantime, they rowed or we ferried them.

Meanwhile, while all this is going on, Runaway gets a call that Dick's mother has had a series of small strokes and isn't expected to live more than a few days. This development isn't altogether unexpected (she was, after all, 96 and in a nursing home), but they felt they had to go back when the old lady died. So we started to make plans to leave, to get to a place where they could leave the boat safely and fly out of easily--which was not Port au Prince, Haiti! (Just getting to that airport could be an ordeal, we were told, and not a safe trip for white people traveling alone. A Swedish cruiser returning to Sweden hired one of the local villagers to accompany her from Ile a Vache to the airport in Port au Prince.) On Monday, as we were about to go in and settle our bill with the hotel/marina and leave within the hour, we got word from one of the locals that the engine had been found--and was in jail with the thief in Madame Bernard. The marina already had sent their Boston Whaler over to pick it up. So we waited with great anticipation to see whether they got everything back (engine, tank, tool box), just part of it, and whether it still would run. Amazingly, everything was recovered and the engine ran. Runaway hoisted it aboard, locked it down, we dropped our moorings and took off for the Caymans at noon.

The 3-day trip was largely uneventful. We didn't have a lot of wind, so ended up motoring quite a bit of the way. Every once in a while we were teased with wind and managed a brief sail, but then it would die, the sails would flap and flog and generally annoy us, we'd haul 'em in and turn on the iron jenny. About the only good thing you can say for motoring in flat calm is that it's easy to sleep on watches. We arrived in Grand Cayman on Thursday afternoon, cleared in, went to dinner, and went to bed. The next morning Runaway got the call that Dick's mother had died in the night, and they headed for Boston that afternoon. We stayed behind as official boat watchers and new-place-scoper-outers. The Caymans, like Bonaire, boast great diving, so in addition to investigating the usual things like grocery stores and laundry opportunities, we checked out the diving.

We ended up staying in Grand Cayman 11 days, diving, dealing with various things that needed repairing that we didn't know needed repairing (turns out Runaway's dinghy engine wasn't in quite as good shape as they thought), having parts shipped in, etc. The typical boat thing. Grand Cayman was ok, if a little pricey and a little touristy. It's quite a sight when there are 5 of those monster cruise-ships all anchored in a line in the harbor off our stern, all disgorging dopey-looking passengers to shop and wander the town with what always looked to us like bewildered, "why-are-we-here?" looks on their faces. I guess people like it, tho. There sure are a lot of them!

On Tuesday morning, 5/7, we dropped our moorings and headed out for our 24-hour run north to Cayo Largo, Cuba. Nice day, good conditions, good wind. This time we sailed the whole way! During the evening, just as we were having dinner in the cockpit, a cute little bird fluttered around us for a while and finally landed on the boat. (We always wonder, where do they come from way out here?? We were about 75 miles from Cuba at the time, which is long way for such a little bird!) He eventually settled on a line wrapped around the steering wheel, which looked to be kind of a precarious perch because the wheel kept moving. I guess he liked the grip. Jim offered him some bread, which he pecked at from Jim's hand but wasn't all that interested. He then just settled in, tucked his head under, and slept there all night. I checked him a couple of times, and even tho the steering wheel was moving around with the autopilot driving, he seemed perfectly content. We concluded this must be a first: someone hopping a boat going to Cuba! By first light, he had retreated to the cockpit floor, and shortly thereafter took off.

It was very windy the next morning as we approached Cayo Largo, and of course the area wasn't marked exactly the way the charts said it was. But Runaway was in the lead so we had the benefit of a scout alerting us by radio of what to expect, including some heart-stopingly shallow water in the entrance channel, as we poked our way in to the marina. And so began our Cuba adventure.

While Cuba is very welcoming to cruisers, it's also very strict about where you can enter and clear in. Cayo Largo was one of those places. We were met on the dock by a flock of officialdom: the marina dock master, the harbor master, customs, immigration, a doctor, and agriculture (some in pairs). They were all extremely polite and pleasant, and all had various amounts of paperwork to complete. The doctor just wanted to know if either of us had been sick lately. Customs had the usual questions about guns and took a cursory look around the boat. The poor guy picked 3 cabinets to open and when he did, everything fell out of them, the contents having, uh, shifted in flight. The guy from immigration, I noticed, was making notes in an appointment/daily diary kind of book. When I looked more closely I could see the page he was writing on was from December 2000. Maybe he was trying to get his diary caught up?

The 2 men from agriculture wanted to know about the food we had on board: chicken? No. Fruit? Yes. Where from? Caymans. They wanted to see it. Poked the apples to see if they were firm. Did we have eggs? Yes. Did we have cheese? Yes. Where from? Curacao. I pulled out and showed him an unopened block of Dutch gouda. They spent a fair amount of time examining this block of cheese, including discussing its price and asking us what currency the price was in (Netherlands Antilles guilders). Eventually they said they had to seal the eggs and the block of cheese. We could open them after we left, but not before. OK, no problem. (I just showed him that particular block of cheese as an example. There was lots more in the refrigerator! Never mind. He got to seal up something.) We had to give him a plastic bag to seal the stuff up in and then he charged us $5 for the little piece of wire he put around the bag. We had an official document about this sealed stuff that we would have to produce, along with the still-sealed stuff itself, when we cleared out of Cuba. But the whole process was painless and the people were very nice. They were very appreciative of and patient with our fractured Spanish; a few of them spoke a little English.

When we later compared check-in notes with a couple of other boats there (one Italian, one American), we discovered we'd gotten off pretty easy. The American boat said the officials took up all their floor boards and went thru every cabinet, and then brought a very sandy and not-too-bright drug dog aboard. The Italian guy said they made him erase all the waypoints in his GPS and then sealed it up. I guess they didn't want him wandering around taking potential invasion waypoints. Ours was mounted in the cockpit and nobody said boo about it... A few days later when another American boat arrived with a couple of people aboard who didn't know hippie was no longer "in," Jim made the untimely transfer of a baggie of boric acid powder to the dock master whose highly infected toe we'd been helping to treat. The boric acid was for soaking the toe. But the customs guy saw the bag, thought it had come from the hippie boat, and took the suspicious white powder away to be tested. Pire, the dockmaster, thought this was a real hoot and teased the customs officer about it as we teased him about his cocaine toe.

Our first order of business was to make arrangements to fly to Havana, which we did on Friday afternoon. Like they say, "if you have time to spare, go by air," and this was no exception. We left the boats at 5 pm, got to our hotel at 9:30 pm, and it was only a 35 minute flight. The airplane was an Anatoly, former Soviet troop carrier, with barely better seats than the soldiers must have had and only 2 fogged-over windows. We boarded via a drop-down ramp in the back (Jim said he felt like yelling "Geronimo" as we left), and in the front was a big bubble that protruded from the port side with a guy sitting there, we guess for visual navigation...?

Our hotel, Las Frailas, was in Old Havana. An old mansion converted to a hotel with a monastery theme, it was a bit pricey but very nice. And once again, the people were wonderful. We had heard that Carter was going to Cuba in May but didn't know till we arrived in Havana that he was due on Sunday. Already there was quite a buzz about his arrival. As it turned out, our hotel was just a couple minutes walk from his, and after watching the arrival ceremony on CNN in our room, we walked the 2 blocks to his hotel and saw them arrive, with "The Bearded One." I don't know how much play Carter's visit got in the States, but it definitely dominated the news in Havana. We were foiled, however, at hearing--or I should say understanding--his speech because he delivered it in Spanish and they didn't provide and English translation down there! What was especially frustrating was not being able to understand the questions from the audience, some of which were more like speeches. We could sorta figure out what the questions were by the way Carter answered them (but it seemed a couple of times even he had trouble figuring out what he was being asked). Although the speech was broadcast there, we learned later that very few people outside of Havana would hear it, and that only selected pieces of it were reported in the scrawny little government paper. (Before we left Cayo Largo I offered Pire the Sunday NY Times we'd gotten in Grand Cayman. When I gave it to him he asked in amazement, "This is all one paper??") I don't know what will come of Carter's visit, but it was certainly an interesting time to have been in Havana.

Havana is a marvelous, if crumbling city. All the books are right about what it must have been like in its "heyday." Some of the old buildings are spectacular. But now it's like an old athlete beyond his prime and gone to seed. You can still see some of the remaining grace and the contours of the physique, but it's drooping and dropping and chipping away from a prolonged lack of maintenance and attention. According to the Lonely Planet guide to Cuba, "each year about 300 buildings [in Havana] collapse." I can believe it. The old city, La Habana Vieja, was declared a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1982 and has undergone a fair amount of restoration since then--fortunately--so you can really get a taste of what was and could be in that area of the city. But the rest is pretty grim and unless something changes there soon, there isn't going to be a lot of hope for it. It will literally be beyond repair. Lonely Planet, in fact, goes on to say, "it's estimated that 88,000 Havana dwellings will have to be demolished" because they're not safe. Housing in Havana is all government controlled and full; you can't move there without a permit, and if you're already there, it's virtually impossible to move to another place within the city, even tho people make quiet, private deals to swap apartments or "buy" something.

The average Joe Cuban makes $10 -12 per month at his government job. And all jobs are government jobs. We met a physician when we delivered the medicines and school supplies to the Jewish Community Center who makes $28 a month and augments her salary by serving as a tour guide (tho not officially, of course). They also get some kind of monthly rice allotment, tho I'm not sure how much. If they have US dollars they can shop in the "dollar stores," but even those can be pretty lean. They struck us as what the stores must have been like in the depression: limited supplies of odd stuff, lots of empty shelf space. There are imported items, all from Europe or South America. You can even get Coca Cola there, made in Mexico. If you don't have dollars, you shop in the peso stores or markets. We never saw a peso grocery store, but did go to a couple of fresh produce markets where the stuff was amazingly cheap. We converted $10 to pesos; I bought $5 worth of flowers and a huge bag full of fresh fruit and vegetables and we still had pesos left over.

We did visit a peso "department store" in the city of Cienfuegos. It was a dingy, single-story area smaller than most Sears tool departments. In it was everything from a live fish aquarium to plumbing parts, to jewelry (with the fish), to shoes, fabric (I only counted 4 bolts), clothes, laundry detergent (in the same case with men's shirts). And the ugliest furniture you've ever seen, including a wooden bed frame with a broken leg. Like the fabric, there were only a few of any one item--not the bazillions we're used to in our stores. There were just a couple pairs of ugly shoes, a couple of out-of-style shirts, a few bars of soap, one or two bottles of hand lotion. Many of the countertops actually had broken glass--not just cracks, but jagged edges exposed. Clothing stores we saw most dealt in "recycled" items.

In Havana, at least where we were and what we saw, everything was priced in US dollars, the currency everyone used, regardless of your port of origin. And everyone wanted a buck. Although the begging wasn't too bad, we had a lot of requests for a dollar. The conversations usually started with, "Hello. Where are you from?" We learned to steel ourselves the minute we heard those 4 signal words. Sometimes it started with a guessing game: "Hello. Are you from Canada? No. Germany? No. Australia. No." Despite the number of Americans there, people are still genuinely surprised when you tell them you're from the United States. And genuinely warm. We never had anyone lurch back in dismay or spit on our shoes when we told them where we were from. Most people went to great lengths to tell us how much they liked Americans (tho not George Bush) and really wished the 2 governments could sort out their differences. And before you leap to conclude that they like Americans because they all want to go to Miami, that's not true. We met a lot of Cubans who are perfectly happy in Cuba and don't want to leave. They're fiercely patriotic, and based on the small, non-scientific poll we took, many are quite loyal to Fidel (as they call him; that, or "the Bearded One," or they make a quick gesture with their hand to indicate a beard when referring to him) or at least that's what they say.

I could go on for pages about Havana and that experience alone, but this is already going to be a record-setter for number of pages so I won't unless you ask for more. We did all the right touristy things there: visited Hemingway's room and various hangouts, including his favorite bar; visited a small, dirt-poor tobacco farm and a small cigar factory where they really do hand roll the cigars, just like it says (Dick and Jim decided this was an opportunity they couldn't pass up so treated themselves to a fresh Cuban cigar). We went to the Museum of the Revolution, which traces with great pride and great anti-CIA vitriol Castro's 1959 take-over, with the aid of his friend and super-mega-hero Che Guevara. As visits to these types of places usually do, this museum exposed once again my woeful ignorance of the history of this era and area. It was particularly interesting to see the story presented from the other side. We were struck everywhere we went in Cuba with the abundance of stuff with "Che's" face on it: entire racks of Che postcards, posters, bad oil paintings, flags, pins, banners, billboards, blown up photographs in offices, books, you name it. Everywhere that distinctive face with the black beret. The other thing you can't help noticing in Havana is the number of early 1950s-vintage American cars on the streets. It was like being on an old movie set, except these cars were in regular, day-to-day use.

Our plan had been to take a bus or train or car to a couple of "must see" cities in the central part of the island, but after a few days in Havana Runaway concluded that it was simply too expensive. Lacking access to ATMs, you have to live with what you have--some places will take European credit cards, but not American--so there's no way to get more or to use plastic. You have to be careful. An early return to the boat wouldn't really cause us to give up anything because we would be sailing in that direction anyway and would stop in that area. So we hit the local market for fresh stuff, washed it in the hotel tub, and left at 5:30 the next morning to return to the boats in Cayo Largo and start getting ready for the next phase of our respective adventures. Runaway was heading west along the south of Cuba and then north to return to Florida; we were heading east and then back south. We both planned to be on our way in a day or so.

Silly us. The weather faxes told of a front on its way and the marina staff kept telling us it was going to rain. Between the wind and the cloudy overcast we couldn't go anywhere. If there's one thing you need when negotiating reef waters, especially those around Cuba, it's sunlight to read the water color. The night after we first arrived in Cayo Largo, a French couple on a brand new American catamaran put the boat onto a reef and totaled it. Nobody could believe they'd been out there in the reefs at night because that's what inevitably happens. And since a cloudy day is as good as night when it comes to reading the water, we weren't moving. We waited 5 days, with little to do. Cayo Largo is a resort island with nothing more than a couple of big resort hotels and gorgeous beaches--the most beautiful, soft white sand expanses we've seen anywhere down here. But the only people who can resort there are non-Cubans, i.e., tourists with American dollars. Cubans work on the island and in the resort hotels, but they can't live or vacation there. We met one American at one of the resort hotels when we went to scope it out, but virtually everyone there was European or Canadian.

While we were waiting and preparing to leave, we decided we didn't want to lug around those now old, sealed-up eggs for the next couple of weeks, so we asked that the agriculture guy come back and take them away. We'd give up those jailhouse eggs and get fresh ones. This was no problem, but remember there was also a block of cheese sealed with the eggs that we wanted to keep if possible. Could he re-seal the cheese? No problem. He sealed it back up and charged us another 5 bucks to do it. The next day he came back and said that we should open the cheese and eat it all before we got to Cienfuegos! For reasons that weren't altogether clear, he didn't want us to keep it. So we lopped off big wedges and gave them to our slip neighbors and started eating gouda cheese on everything. The next day he came back again and asked if the cheese was all gone! We told him we were working on it... Fortunately the cheese police didn't come back, as we still had a lump of the stuff with us when we left for Cienfuegos!

After 5 days the pesky and persistent front looked like it was ready to pass, so we made ready to leave. Runaway did just that: took a window and ran west. We ended up waiting yet another day because the conditions still looked pretty rough for going east--once again Asylum was going to go weather--and we wanted to minimize the pounding we'd take. Because of the slipping days, we reluctantly decided to forgo our planned stops at 2 cays on the way to the city of Cienfuegos and go directly there in an overnighter. It was a little windier than we had hoped (marinas tend to be put in protected areas so it's often hard to tell what's really going on "outside" when you're sitting at the dock) and it was a lousy trip. In addition to pounding into the seas, we had an adverse current that slowed us down. Then there was the "exclusion zone" we had to go around--an area along the south coast that includes the infamous Bay of Pigs--and a shallow bank to avoid. I experienced a new personal first on this trip: giving back my dinner. Didn't feel seasick at all, but suddenly, well, you get the idea. Yuck. And then in the morning, as we approached Cienfuegos, the autopilot started to act squirrelly and wouldn't hold a course. Fortunately we were close enough that hand-steering for the last couple of hours wasn't a problem, but given the distances that we still had ahead of us, not having a functioning auto-pilot was gonna be a BIG problem.

We pulled into the small, somewhat dilapidated marina in Cienfuegos and once again were met by officialdom waiting for us on the dock. You have to clear in and out of every port, even domestically (Cuba's not alone in this; we had to do the same in Venezuela, where they charged fees in each place). Once again, everyone was very nice, very welcoming, and very helpful. The customs guy took a cursory look below, and stuff fell out of the cabinets onto him, too. We washed the layer of salt off the boat just in time for the skies to open up and finish the rinse while we took a much needed nap. The busted auto-pilot would wait for tomorrow.

Cienfuegos is a good-sized city, with interesting old architecture and once-beautiful buildings, but also going to seed. When the Soviet Union collapsed and turned back into Russia, with its own boatload of economic problems, they dropped their economic support of Cuba like a hunk of dead lead. Cuba went into an economic tailspin during the early 1990s, which I, for one, certainly didn't pay much attention to at the time, but the results were clearly evident there. With no money for any kind of maintenance, things just decay. While the Cubans we talked to thought the school and medical systems were good as far as the people were concerned (i.e., the teachers and doctors), the facilities were crumbling. What has always been touted as a good medical system by the Cubans, many are now afraid to use. In one family we met the aunt had just returned from Miami where she went to have surgery because she was so fearful of the conditions in the local hospital. Parents we talked to at the Jewish Community Center in Havana where we delivered the medicines and school supplies said the teachers were good, but the school buildings were not, and tho supposedly education was free in Cuba, they had to pay for everything. Only the teachers were "free."

The economic strain continues, which is why tourism is being reluctantly encouraged: it brings in American dollars (if not actual Americans with dollars). One of the effects however, is to create a significant have/have not society, which is the antithesis of what the Bearded One says he wants. There's an active underground economy for locals to make dollars, which they desperately need to augment their meager government wage. We met a delightful young couple, and then the rest of the family, in Cienfuegos. He makes $10 a month as an auto mechanic, she $6 as a shop attendant. He moonlights as a tour guide, tho if you hire him, or any of these "tour guides" for that matter, you quickly learn that if you're stopped by the police you say that these are your "friends." You're only supposed to use taxis, tour guides, restaurants, etc. with licenses to accept dollars because then the gov't can get the dollars from its licensees. In Cienfuegos the common mode of public transportation for locals is by horse-drawn cart, for a peso (about 4 cents). But not for tourists. Tourists are supposed to use taxis that charge dollars. All the tourists use the horse-drawn carts anyway, including us, paying a little more than the locals. But the whole time we were in one, the driver, who was charming and spoke in slow, carefully articulated Spanish so we could understand him, took back streets as far as possible and watched anxiously over his shoulder for the police when we were on the main road. We weren't the ones that were going to be in trouble he explained to us; he was, but it was still worth it to them to be able to make a few dollars here and there. We also learned from our "friends" that Cubans are not allowed to eat lobster, shrimp, or "beefsteak"--these are only for tourists--and if they get caught with them, could lose their housing and end up in jail. Nor could Cubans come onto the docks at the marina. We met a young waiter who asked if he could bring his wife and come see the boat. We said sure, but when they showed up the next day at the appointed hour, the harbormaster emphatically said "No!" to taking them to the boat. All in all, it was a nice place to visit, but I wouldn't want to live there.

In addition to doing the tourist thing, we were doing cruiser things: fixing boat stuff, meeting other cruisers, and planning for the next part of the trip, keeping a keen eye on the weather. Before we could go anywhere, tho, Jim had to tackle the autopilot problem. He feared that something in the drive unit had failed, but when he took the unit apart it appeared that the magnetic clutch was loose and a simple tightening of the screw that had fallen out seemed to do the trick. "Dodged a bullet there!" says we, and thanked our lucky stars it was nothing that required parts to be shipped in! Back in business...we thought.

The only other cruisers in the marina at the time were a young Danish couple on their way to Florida. They'd come across the Atlantic in their sturdy little 31 ft boat, Pikero, and were on their way around the west end of Cuba and then north to cruise the eastern United States. Like us, they were waiting for weather to leave Cienfuegos, and we spent a delightful couple of days getting to know them, trading waypoints, and telling them about the glories of the Chesapeake Bay. Just like US cruisers have their radio weather nets and weather gurus, the Danes have theirs, only in Danish. Their guru was in Panama, giving them nightly advice about when to head west, so they were sharing with us what he was saying about the area, which was pretty much what our faxes were telling us: not good. Big, stationary low pressure system sitting off south central Cuba, right where we were and wanted to go. Very unusual, says everybody. But nonetheless nasty, kicking up the seas and generating squalls. But then the faxes started to suggest the low was moving and that conditions were going to improve. Pikero waited one more day, grabbed what looked like a good window and headed west. We hooked them up by radio with Runaway, a week or so ahead of them on the same route. The 3 of us arranged to check in by radio every morning and evening.

By now we were getting a little antsy to leave because we still had a lot ground to cover and June 1, the official start of the hurricane season, was only a couple days away. June is a low probability month for hurricanes; even our insurance didn't require us to be below the specified latitude until July 1, but the fact is, it was still gonna be hurricane season soon and we didn't want to stay there any longer than necessary. In addition, we were running out of visa time (30 days), insurance rider time (30 days), and lack-of-ATM time. We also wanted to spend some time in the supposedly beautiful, fish and lobster-abundant, superb cruising ground cays known as Los Jardines de la Reina, Gardens of the Queen. So when it looked like we, too, had a break in the weather, we took it. Got the officials back on the boat, checked out of Cienfuegos, and set out on the morning of May 29 for an overnighter to our first stop in the cays.

It was a nice day. There were big swells at the entrance to the harbor, but they were the big rolly kind (not choppy and breaking) and didn't seem too bad. Conditions got a little sloppier as the day went on, but by about 5:30 it was flat calm, we were motoring along nicely, and started to look forward to an easy motor-sail night. Silly us. Around 7:30 the autopilot started to act up again and quit working all together. So much for Jim's fix. We had to unload all the stuff in one locker to get at the deep storage area under it where the old, now-backup autopilot was stored. The contents of the locker were piled on the counter top while Jim was installing the backup and I was on the radio with Pikero at 8 getting the Danish guru's weather forecast. All of a sudden, everything went flying across the galley, making one helluva mess and racket. Seems the back-up auto-pilot wasn't cooperating and decided to make a hard left. Jim wasn't able to get it working, so we prepared ourselves for a night of hand steering, again thinking at this point it wasn't going to be too bad. I put the galley stuff away and then took the helm while Jim checked on our position and course.

It was about then that things started to deteriorate fast. The wind picked up and there were squall lines on the radar. Pretty soon there was lightning everywhere, the wind continued to increase, and it was raining hard. And of course it was very dark. So began our night from hell. I was on the helm, Jim watching the electronic charts and the radar to see if we could dodge the squalls, but they were huge. Covered almost the whole radar screen. Nowhere to run, especially if we had the remotest hope of getting to where we were going in daylight the next day because we were making so little headway by now with the mounting seas and adverse current. The boat was actually handling quite well and I wasn't working too hard to steer, but in the dark and pouring rain I was getting to the point where I was shivering. And the constant lightning was very unnerving. With every flash I winced and made sure my hands were touching only the wood part of the wheel. As the night wore on, tho, after hours of lightning, I found myself wincing less and less and sat there at the helm wondering if that's what it's like in battle, with bullets whizzing all around you: eventually you just don't think about it and do what you have to do. For all you combat veterans, I'm not saying that our situation was like being shot at, but it was pretty rotten out there, and there wasn't a damn thing we could do about it but to do what you gotta do to keep the boat and crew safe. I just kept telling myself that the lightning we were experiencing wasn't the "striking" kind anyway. It was causing the sky to light up, but we weren't seeing the sharp, zig-zag-like streaks that take aim for something (like a mast).

We pretty much did this for about 8 hours. Just when one squall passed and the radar looked clear, we'd see the tell-tale black blob appear on the edge of the screen and grow into another monster. Most of the night the winds were in the high 30-knot range. I saw as high as 41 on one of my stints at the helm; Jim saw 45. It was too dark to really see how high the seas were, which was probably a good thing. There was no dodging the squalls, which sometimes you can do by changing course a little if they're not too big, but these were enormous and we didn't have much room to negotiate. On top of everything else, we were approaching a shallow bank that was plenty deep to sail across but in shallow areas that are near deeper water the waves tend to pile up and get higher because there's no place for the water to go. So we didn't want to make things worse by putting ourselves on a course to go over the bank. But that's exactly where we were being pushed. I suggested that we go down its west side and then back east around the bottom, even tho that was "out of our way," but Jim wanted to try to stay east of it (remember that our goal is east). That didn't work, and in the end, what we did looked something like this:

Sorry... the drawing wouldn't import into the blog. But It was messy...

At some point during the night when I was below and Jim was on the helm, I heard a radio broadcast on channel 16 but realized too late that it was an American voice in English. We always have the radio on when we're underway, but rarely heard anything in those parts and if we did, it was usually in Spanish. So when this one came over, it took me a minute to realize I was hearing English and that what I had just heard was the end of lat/long coordinates. Then the voice said, "All vessels should check their emergency equipment and keep a sharp lookout. US Coast Guard out." Lookout for what?? Clearly it was the Coast Guard from Guantanamo Bay since it came over VHF 16. I tried to call them to find out what they'd said, but got no answer. We were just too far away. My first thought was that they were advising all vessels in the area of deteriorating weather conditions (hence "check your emergency equipment") but as we talked about it later we concluded that they must have received some kind of emergency signal and were telling boats to check to see if their emergency signal equipment had gone off. Meanwhile, still thinking it must have something to do with the weather, we decided to use the SSB emergency frequencies to try to contact the Coast Guard to see what it was. Jim called a couple of times and finally got an answer from the Coast Guard in Kodiak, Alaska! We told them where we were, what the conditions were and that we'd heard this broadcast on 16 but didn't know what it was. Could they find out if some kind of warning was being issued and if so, for what? We waited what seemed an eternity, and next thing, Jim's talking to the Coast Guard in the Chesapeake Bay! In the end, all they did was read to him the weather forecast we already had. A lotta good that did us. We never did find out what that broadcast was about.

Continued in Inmate Update 10, Part 2

When last we left you in late November, we'd just arrived in Bonaire, the "B" and eastern-most of the ABC islands (Aruba, Bonaire, and Curacao), known as the Netherlands Antilles. After a couple of weeks there--long enough to get our advanced dive certification and log a bunch more dives--we headed west to Curacao, where Asylum was hauled from the water on a marine railway and we were hauled from the islands on a 737. Fast-forwarding through the next few weeks, we returned to the boat, with its shiny new bottom and fresh red stripes, in late January, waited for a good day to slog back east to Bonaire, and got back there in early February. Curacao is ok, but not a good place for cruiser/divers to hang out for any long period of time. It's very built up, has its own version of a beltway, terrible traffic, and a smoke-belching oil refinery. Bonaire, on the other hand, has not a single traffic light on the island, you can walk everywhere you need to go, and can dive off the side of your boat! There was no question that this was where we were going to hang out for a while and figure out our plan for the rest of the year. (OK, so the diesel was 1/3 the cost in Curacao, but we're a sailboat, right?)

When we decided late last year not to go thru the Panama Canal early this year, it meant we had to come up with something to do with ourselves till the next transit window--or until we changed our minds again. (Cruisers are nothing if not flexible. Most of us use jello as the metaphor for the consistency of our "plans," as in: "still liquid" or "firming up" or "not set yet," or "melted.") As I think I've mentioned before, while it may seem that cruisers are free to come and go whenever and to wherever they please, this is only what the magazines tell you. In fact, it's not at all true. We are slaves to and victims of annual weather patterns and opportunistic "weather windows." Some of these windows only open once a year, so if you dawdle, hesitate, or otherwise manage to miss them, you wait a year. That's where we were in early Feb upon returning to Bonaire: diving a lot, and deciding what to do until we decided what to do.

A seed planted upon our arrival in Bonaire in November already was starting to germinate. We had met a couple on a boat called Runaway when we got there. They had recently completed a 7-year circumnavigation, he at the age of 72 and she 70! They were quite remarkable, and Asylum and Runaway clicked immediately. They were also avid divers, putting us to shame (or at least me) the way they could haul themselves up into their dinghy after a dive. They had mentioned their desire/plan to go to Cuba in April. Why don't we come with them? The fact is, we'd wanted to go to Cuba. Supposedly fabulous cruising, especially along the south coast, wonderful people, and still for all kinds of reasons, a "unique" place to visit in the Caribbean. Seed planted.

We mulled. Looked at charts. Talked it over with ourselves and with them. The trip made sense for Runaway: they were planning to head for the Bahamas. But we were still "planning" to head south (eventually), and Cuba was north. A long way north as far as a sailboat is concerned. And not only was Cuba north, it was northwest, which was good for getting up there but not good for getting back. So we continued to ponder, study the charts, the pilot charts, the cruising guides, and others' notes and experiences. It seemed to be do-able, and, well, what else did we have to do? And so, with part gulp and part what-the-hell, we decided to go to Cuba with Runaway in April.

When they were in the States in March, they gathered cruising guides and charts for both of us, but most importantly, obtained a license from a Jewish humanitarian organization in Boston with a "mission" in Havana, that made our visit sponsored and "legal." (There's a lot of confusion about if/how Americans can go to Cuba. The bottom line is that Americans can go to Cuba, but if you're not sponsored or there with the permission of the US gov't, you can't spend any money. Among American cruisers, the rule of thumb is "find a Canadian and go with them.") They also brought back with them a large supply of OTC medicines, toothpaste and toothbrushes, vitamins, etc., for us to deliver to the mission. To all of that we added soaps and school supplies--all reportedly much-needed items for the average Cuban. Not only that, but a local priest they met in Boston also gathered a huge box of children's clothes for us to take to Ile a Vache, Haiti, one of the planned stops on the way to Cuba. We were ready to go.

Our planned route (get out your maps!): Bonaire to Curacao (a short day sail). Curacao to Ile a Vache, a small island off the SW coast of Haiti's main island (3 days). Ile a Vache to Jamaica (about 2 days). Jamaica to one of the Cayman Islands (24 hours). Caymans to Cayo Largo, an island on the south Coast of Cuba (24 hours), where we would clear in. We were pleased to be traveling with Runaway, seriously experienced cruisers who said they simply "didn't do" bad passages and just waited for weather, as long as it took to get favorable conditions. So on April 7 we left Bonaire for Curacao, where we planned to stop only a day or two, long enough to do some add'l provisioning and buy the extra soap and school supplies. But what we thought was going to be a good window wasn't. The weather piped up north of us, right where we were headed, and we had to wait a week for the seas to come back down.

They did, and on April 13 we were ready to go. Pulled up the anchor and were on our way out of the anchorage behind Runaway when they turned around and headed back in. The wind-speed indicator on the top of their mast was stuck and wasn't doing any indicating so they matter-of-factly re-anchored and sent 73-yr old Dick smartly up the mast to unstick it. We circled slowly for about 45 minutes while they did their thing and then off we went on our 3-day trip, pretty much straight north, to Ile a Vache.

Conditions were great, the sailing was good, and we were off to a promising start. We had decided to try the quarter berth as our passage berth this time rather than sleeping in the main salon as we had on past passages. We normally sleep in the V-berth (at the bow of the boat), but underway there's simply too much motion up there so we move to the center, or this time, farther aft, where the boat's motion is less. We were on a 3-day starboard tack (sails on the port side), so as the boat heeled, we rolled into the port bulkhead and wedged ourselves in with a pillow. It was a comfortable little nest for the 3-4 hours of sleep we traded off getting. We also seemed to find our stride on a watch schedule this time. Before, we'd been kind of loose about who slept when, but all the books say to find one that works for you and stick to it. We arranged things by our natural rhythms--me the night owl, Jim the morning person--and managed to get about 3 hours of sleep on each of 2 night watches, with cat-naps during the day. It worked pretty well, tho the books also say that passages of 1-3 days are the hardest because it takes a good 3 days to really get into the watch rhythm.

This was a great 3-day passage. Caught a tuna. Visited by a pod of high-spirited and high jumping dolphins. Intensely thick stars (tho no moon). Wind picked up the 3rd night, it got kinda lumpy, and we had to mess with sails a few times, but it wasn't too bad. And then on the morning of the 16th we could see the island of Hispaniola (Haiti on the left, the Dominican Republic on the right) on the horizon, with our destination, the little island of Ile a Vache (Island of the Cow) just ahead. Everywhere around the coast were fishermen, some in leaky little dugout canoes that we wouldn't take out on a flat lake on a calm day. Others were in amazing, hand-built wooden sail boats, with what looked like bedsheets for sails. And everywhere, reminiscent of the crab and lobster pots in the Chesapeake and Maine, were fish traps! Unlike the bright colored floats in the north, these were often clear plastic coke bottles that you couldn't see until you were on top of them, about to wrap your prop with their lines. But for the sun and one of us on the bow yelling to throw the engine into neutral any number of times, Jim (!!) would have been diving on the prop...

Overall our passage lumps were pretty minor: the staysail halyard was almost chafed thru (an easy cut and fix); the stern running light flickered on and off a few times (Jim checks wiring); a hank broke on the staysail (put a new one on); the mast rivets for the port-side lazy jacks broke--lazy jacks are a string and pulley system that contains the mainsail when it's reefed and lowered--(Jim goes up the mast and replaces the rivets). But we had a few days to work on these.

Ile a Vache was a study in contrasts. On the one hand there was a lovely resort hotel. A French couple, Didier and Francoise, had spent the past 5 years building this hotel/resort with a small marina operation that had only recently opened and was in its fledgling stage of operation. The setting was idyllic: the hotel perched on a hill overlooking palm trees, bougainvillea, beaches, and off in the distance, beautiful Hispaniola. But the rest of the island of Ile a Vache is National Geographic territory: no roads, no running water, no electricity; women carrying enormous bundles (often in huge aluminum tubs) on their heads; thatch roof huts; little naked kids running around, playing with sticks or stuff they find on the beach. From the moment of our arrival we had people coming to our boat in ratty, leaky little dugout canoes (literally dug out), usually paddling with a piece of wood--rarely a real paddle, and bailing constantly--to ask for work, to sell or trade something, or just to ask for something. Our visitors were almost always young men and little boys, only once were there 2 young girls in the canoe. They spoke Creole mostly, some French, and a few knew a few words of English (especially, "What is your name?" and "Give me something!"). Sometimes there were 3 or 4 of these little boats full of kids hanging off the side of Asylum, banging into each other and to us. Some came trying to sell little limes ("citrons," about the diameter of a quarter); others may have a tomato or an egg or a scrawny little fish, or a shell they proffered. Interestingly, lots of them asked for "un stylo" (a pen) in trade. We had our stash of school supplies, including pens and pencils, for Cuba so broke into that as we accumulated more limes than we could use in a year. Some asked for "a bon bon" (a piece of candy), a few wanted dictionaries or books. One little boy wanted a red T-shirt. We didn't have any red ones, but pulled out a pile we were willing let go and let him pick the next best thing to red. After a while, these relentless visits wear you down, and we would spend more and more time below, out of sight, to avoid having to deal with them. "Urchins at 2 o'clock!" one of us would alert the other when we saw a paddler approach. Sometimes they'd give up and go away if you didn't respond to their calls of "Hello. Hello. Hello." But some could out-wait you, just hanging off the side, knowing you were in there and eventually would have to come up. For these we mastered in French, "We're very busy now," "Nothing today, thank you," "Good-bye" or, eventually, a firm but polite version of "Get lost!"

We did hire a couple of the young men to do some boat work for us. One of the things we were going to do in Bonaire, but successfully put off doing, was polish all the stainless on the boat--a necessary but tedious task. We had learned that the going wages were $3 - 5 a day, so this seemed like a win-win situation to us: these guys got the work they needed and we didn't have to polish the stainless! The two we hired worked very diligently and did a great job. They also washed and waxed the hull--another job we'd put off doing in Bonaire. Sometimes procrastination pays!

Thursday was market day in the island's main "city" of Madame Bernard. The only way to get there from where we were was by dinghy, by foot, or on horseback. The walk, we were told, was a good 2 hours over muddy trails, and we didn't have a horse... So with a young man from the village, Wagner, as our local guide, we set out in the dinghy for the 20 minute ride along the impressive north coast of Ile a Vache. Many vendors come from the main island, off to our left, in small, locally-built sail boats. The passage between the 2 islands was full of them that morning, and many of these boats were full to the gunwales with people. I use the term "city" because they do, but that's a stretch. This is one rough place. No streets, no sidewalks, no power. It had rained torrentially the last couple of days (the source of all fresh water on the island) and the market area was a flooded mud swamp. Horses were tethered everywhere. Most of the people were barefoot. We visited an orphanage, run by a French Canadian nun, where we delivered the bags of clothes that Runaway had brought from Boston. Most of the kids there were not merely orphans, but also had medical problems (we saw several with CP). We also visited an elementary school, where all the kids were in brown bottom (short or skirts) and bright yellow shirts. ALL of the girls also were festooned with bright yellow ribbons in their hair. About half were barefoot. It costs a family anywhere from $20 to $40 a year to send 1 child to elementary school. Many families with multiple children (and they all seem to have a LOT!) can only send 1 kid for 1 year, then maybe another kid for the next year, or maybe not anybody. Most of the people we talked to in the village near where we were anchored had only been to school fleetingly, and in fact money to go to school was one of the things they often asked for.

Despite the steady stream of "visitors" to the boat, all of them peering in with great curiosity, we were told that security was no problem. "No need to lock the dinghy at night," said fellow cruisers who'd been there a while. So imagine our surprise when Jim pokes his head out to survey the scene early on our 4th morning there and sees the painter to Runaway's dinghy hanging limp and dinghy-less at the side of their boat. Continuing to survey the scene he sees their dink on the beach nearby, sans engine and gas tank (and, we learned later, a tool box they kept in there). Ohmygoodness did this generate a buzz and flurry of activity! The police from the main island were brought in. The village chief got involved. The villagers were angry, not only because it ruined their good name but more importantly, we were told, that having the police snooping around interfered with their rather active drug activities. The hotel owners (who provide virtually all of the employment to the village) basically said to the locals, "Until the engine is found and returned, don't even think about bothering these boats." We were amazed at how quiet things suddenly got in the anchorage. No visitors. No little voices calling "Hello. Hello. Hello. Give me something." But everybody in the village was pretty sure they knew who did it and everybody was looking for the guy. Cautiously optimistic that they might get the engine back (when this happened a few years ago, the engine was recovered), Runaway nonetheless started calling Jamaica and Grand Cayman to see if/where they could get a new engine. In the meantime, they rowed or we ferried them.

Meanwhile, while all this is going on, Runaway gets a call that Dick's mother has had a series of small strokes and isn't expected to live more than a few days. This development isn't altogether unexpected (she was, after all, 96 and in a nursing home), but they felt they had to go back when the old lady died. So we started to make plans to leave, to get to a place where they could leave the boat safely and fly out of easily--which was not Port au Prince, Haiti! (Just getting to that airport could be an ordeal, we were told, and not a safe trip for white people traveling alone. A Swedish cruiser returning to Sweden hired one of the local villagers to accompany her from Ile a Vache to the airport in Port au Prince.) On Monday, as we were about to go in and settle our bill with the hotel/marina and leave within the hour, we got word from one of the locals that the engine had been found--and was in jail with the thief in Madame Bernard. The marina already had sent their Boston Whaler over to pick it up. So we waited with great anticipation to see whether they got everything back (engine, tank, tool box), just part of it, and whether it still would run. Amazingly, everything was recovered and the engine ran. Runaway hoisted it aboard, locked it down, we dropped our moorings and took off for the Caymans at noon.

The 3-day trip was largely uneventful. We didn't have a lot of wind, so ended up motoring quite a bit of the way. Every once in a while we were teased with wind and managed a brief sail, but then it would die, the sails would flap and flog and generally annoy us, we'd haul 'em in and turn on the iron jenny. About the only good thing you can say for motoring in flat calm is that it's easy to sleep on watches. We arrived in Grand Cayman on Thursday afternoon, cleared in, went to dinner, and went to bed. The next morning Runaway got the call that Dick's mother had died in the night, and they headed for Boston that afternoon. We stayed behind as official boat watchers and new-place-scoper-outers. The Caymans, like Bonaire, boast great diving, so in addition to investigating the usual things like grocery stores and laundry opportunities, we checked out the diving.

We ended up staying in Grand Cayman 11 days, diving, dealing with various things that needed repairing that we didn't know needed repairing (turns out Runaway's dinghy engine wasn't in quite as good shape as they thought), having parts shipped in, etc. The typical boat thing. Grand Cayman was ok, if a little pricey and a little touristy. It's quite a sight when there are 5 of those monster cruise-ships all anchored in a line in the harbor off our stern, all disgorging dopey-looking passengers to shop and wander the town with what always looked to us like bewildered, "why-are-we-here?" looks on their faces. I guess people like it, tho. There sure are a lot of them!

On Tuesday morning, 5/7, we dropped our moorings and headed out for our 24-hour run north to Cayo Largo, Cuba. Nice day, good conditions, good wind. This time we sailed the whole way! During the evening, just as we were having dinner in the cockpit, a cute little bird fluttered around us for a while and finally landed on the boat. (We always wonder, where do they come from way out here?? We were about 75 miles from Cuba at the time, which is long way for such a little bird!) He eventually settled on a line wrapped around the steering wheel, which looked to be kind of a precarious perch because the wheel kept moving. I guess he liked the grip. Jim offered him some bread, which he pecked at from Jim's hand but wasn't all that interested. He then just settled in, tucked his head under, and slept there all night. I checked him a couple of times, and even tho the steering wheel was moving around with the autopilot driving, he seemed perfectly content. We concluded this must be a first: someone hopping a boat going to Cuba! By first light, he had retreated to the cockpit floor, and shortly thereafter took off.

It was very windy the next morning as we approached Cayo Largo, and of course the area wasn't marked exactly the way the charts said it was. But Runaway was in the lead so we had the benefit of a scout alerting us by radio of what to expect, including some heart-stopingly shallow water in the entrance channel, as we poked our way in to the marina. And so began our Cuba adventure.

While Cuba is very welcoming to cruisers, it's also very strict about where you can enter and clear in. Cayo Largo was one of those places. We were met on the dock by a flock of officialdom: the marina dock master, the harbor master, customs, immigration, a doctor, and agriculture (some in pairs). They were all extremely polite and pleasant, and all had various amounts of paperwork to complete. The doctor just wanted to know if either of us had been sick lately. Customs had the usual questions about guns and took a cursory look around the boat. The poor guy picked 3 cabinets to open and when he did, everything fell out of them, the contents having, uh, shifted in flight. The guy from immigration, I noticed, was making notes in an appointment/daily diary kind of book. When I looked more closely I could see the page he was writing on was from December 2000. Maybe he was trying to get his diary caught up?

The 2 men from agriculture wanted to know about the food we had on board: chicken? No. Fruit? Yes. Where from? Caymans. They wanted to see it. Poked the apples to see if they were firm. Did we have eggs? Yes. Did we have cheese? Yes. Where from? Curacao. I pulled out and showed him an unopened block of Dutch gouda. They spent a fair amount of time examining this block of cheese, including discussing its price and asking us what currency the price was in (Netherlands Antilles guilders). Eventually they said they had to seal the eggs and the block of cheese. We could open them after we left, but not before. OK, no problem. (I just showed him that particular block of cheese as an example. There was lots more in the refrigerator! Never mind. He got to seal up something.) We had to give him a plastic bag to seal the stuff up in and then he charged us $5 for the little piece of wire he put around the bag. We had an official document about this sealed stuff that we would have to produce, along with the still-sealed stuff itself, when we cleared out of Cuba. But the whole process was painless and the people were very nice. They were very appreciative of and patient with our fractured Spanish; a few of them spoke a little English.

When we later compared check-in notes with a couple of other boats there (one Italian, one American), we discovered we'd gotten off pretty easy. The American boat said the officials took up all their floor boards and went thru every cabinet, and then brought a very sandy and not-too-bright drug dog aboard. The Italian guy said they made him erase all the waypoints in his GPS and then sealed it up. I guess they didn't want him wandering around taking potential invasion waypoints. Ours was mounted in the cockpit and nobody said boo about it... A few days later when another American boat arrived with a couple of people aboard who didn't know hippie was no longer "in," Jim made the untimely transfer of a baggie of boric acid powder to the dock master whose highly infected toe we'd been helping to treat. The boric acid was for soaking the toe. But the customs guy saw the bag, thought it had come from the hippie boat, and took the suspicious white powder away to be tested. Pire, the dockmaster, thought this was a real hoot and teased the customs officer about it as we teased him about his cocaine toe.

Our first order of business was to make arrangements to fly to Havana, which we did on Friday afternoon. Like they say, "if you have time to spare, go by air," and this was no exception. We left the boats at 5 pm, got to our hotel at 9:30 pm, and it was only a 35 minute flight. The airplane was an Anatoly, former Soviet troop carrier, with barely better seats than the soldiers must have had and only 2 fogged-over windows. We boarded via a drop-down ramp in the back (Jim said he felt like yelling "Geronimo" as we left), and in the front was a big bubble that protruded from the port side with a guy sitting there, we guess for visual navigation...?

Our hotel, Las Frailas, was in Old Havana. An old mansion converted to a hotel with a monastery theme, it was a bit pricey but very nice. And once again, the people were wonderful. We had heard that Carter was going to Cuba in May but didn't know till we arrived in Havana that he was due on Sunday. Already there was quite a buzz about his arrival. As it turned out, our hotel was just a couple minutes walk from his, and after watching the arrival ceremony on CNN in our room, we walked the 2 blocks to his hotel and saw them arrive, with "The Bearded One." I don't know how much play Carter's visit got in the States, but it definitely dominated the news in Havana. We were foiled, however, at hearing--or I should say understanding--his speech because he delivered it in Spanish and they didn't provide and English translation down there! What was especially frustrating was not being able to understand the questions from the audience, some of which were more like speeches. We could sorta figure out what the questions were by the way Carter answered them (but it seemed a couple of times even he had trouble figuring out what he was being asked). Although the speech was broadcast there, we learned later that very few people outside of Havana would hear it, and that only selected pieces of it were reported in the scrawny little government paper. (Before we left Cayo Largo I offered Pire the Sunday NY Times we'd gotten in Grand Cayman. When I gave it to him he asked in amazement, "This is all one paper??") I don't know what will come of Carter's visit, but it was certainly an interesting time to have been in Havana.

Havana is a marvelous, if crumbling city. All the books are right about what it must have been like in its "heyday." Some of the old buildings are spectacular. But now it's like an old athlete beyond his prime and gone to seed. You can still see some of the remaining grace and the contours of the physique, but it's drooping and dropping and chipping away from a prolonged lack of maintenance and attention. According to the Lonely Planet guide to Cuba, "each year about 300 buildings [in Havana] collapse." I can believe it. The old city, La Habana Vieja, was declared a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1982 and has undergone a fair amount of restoration since then--fortunately--so you can really get a taste of what was and could be in that area of the city. But the rest is pretty grim and unless something changes there soon, there isn't going to be a lot of hope for it. It will literally be beyond repair. Lonely Planet, in fact, goes on to say, "it's estimated that 88,000 Havana dwellings will have to be demolished" because they're not safe. Housing in Havana is all government controlled and full; you can't move there without a permit, and if you're already there, it's virtually impossible to move to another place within the city, even tho people make quiet, private deals to swap apartments or "buy" something.

The average Joe Cuban makes $10 -12 per month at his government job. And all jobs are government jobs. We met a physician when we delivered the medicines and school supplies to the Jewish Community Center who makes $28 a month and augments her salary by serving as a tour guide (tho not officially, of course). They also get some kind of monthly rice allotment, tho I'm not sure how much. If they have US dollars they can shop in the "dollar stores," but even those can be pretty lean. They struck us as what the stores must have been like in the depression: limited supplies of odd stuff, lots of empty shelf space. There are imported items, all from Europe or South America. You can even get Coca Cola there, made in Mexico. If you don't have dollars, you shop in the peso stores or markets. We never saw a peso grocery store, but did go to a couple of fresh produce markets where the stuff was amazingly cheap. We converted $10 to pesos; I bought $5 worth of flowers and a huge bag full of fresh fruit and vegetables and we still had pesos left over.

We did visit a peso "department store" in the city of Cienfuegos. It was a dingy, single-story area smaller than most Sears tool departments. In it was everything from a live fish aquarium to plumbing parts, to jewelry (with the fish), to shoes, fabric (I only counted 4 bolts), clothes, laundry detergent (in the same case with men's shirts). And the ugliest furniture you've ever seen, including a wooden bed frame with a broken leg. Like the fabric, there were only a few of any one item--not the bazillions we're used to in our stores. There were just a couple pairs of ugly shoes, a couple of out-of-style shirts, a few bars of soap, one or two bottles of hand lotion. Many of the countertops actually had broken glass--not just cracks, but jagged edges exposed. Clothing stores we saw most dealt in "recycled" items.