Asylum

22 June 2019 | Straits Quay Marina, Penang, Malaysia

17 July 2016 | Penang, Malaysia

20 February 2016 | Penang, Malaysia

02 October 2015 | Thailand

11 April 2015 | Krabi Boat Lagoon Marina, Thailand

25 December 2014 | Langkawi, Malaysia

04 June 2014 | Philippines

07 January 2014 | Brookeville, MD

04 July 2013 | Subic Bay Yacht Club, Philippines

31 October 2012 | Palau

02 December 2011 | Hermit Islands, Papua New Guinea

08 November 2011 | Maryland, USA

15 May 2011 | Kavieng, New Ireland, PNG

26 April 2011 | Kavieng, New Ireland

26 March 2011 | Kokopo, New Britain, Papua New Guinea

16 March 2011 | Kokopo, New Britain, Papua New Guinea

12 February 2011 | From Peava again

05 February 2011 | Solomon Islands

01 December 2010 | From Lola Island, VonaVona Lagoon, Solomon Islands

30 November 2010 | Peava, Nggatoke, Solomon Islands

Inmate Update #12: Cartagena to San Blas Islands

08 July 2003 | San Blas Islands, Panama

Forgive me, readers, for I have lagged. It's been 9 months since the last Update! We are in the idyllic San Blas Islands of Panama where we usually don't know what time it is, rarely know what day it is, and the weeks slip by unnoticed. After the teeth-rattling, bone-bouncing bash from Haiti in June last year and our run-in with thug-cum-pirates in late September in Colombia, we were looking forward to some seriously dull, uneventful times ahead. And, while these past months have been neither dull nor uneventful, they've been muy tranquillo in comparison.

We left Cartagena in mid-January after 3 ½ glorious months there. On the one hand we hated to leave its comforts and charms, but on the other, we were ready to be out of a marina swinging on the hook in the fabled blue-water, palm-infested, white-sand islands of the San Blas. In Cartagena one of our slip-mates was Ithaka, with Bernadette and Douglas aboard, she the former editor of Cruising World magazine. They were headed back to the San Blas at the same time so we ended up traveling with them for about 2 months--an immeasurable cruising treat for us.

For most people, Panama is known for two things: the Canal and our famous spat with its notorious thug, Noriega, back in the late 80s. The San Blas should be added to the list! This jewel chain of 400 islands--many small enough to leap across--and coral reefs stretches about 130 miles along Panama's Caribbean coast. The vast majority of the islands are uninhabited, and on those that are (habited, that is) live the Kuna Indians, an indigenous tribe of about 70,000. They're a stout (second only to the pygmies in shortness of stature), tenaciously traditional bunch, always described in the guide books as "fiercely independent." In 1925 they staged a sly rebellion against the Panamanian government--which they celebrate and reenact every year with faithfully rendered street theater--and became the "autonomous region" of the San Blas (Kuna Yala in their language).

This is a place time just hasn't paid much attention to. The people still live in thatched huts, one for sleeping (in hammocks) and another for cooking (over wood fires kept alight with 4 large logs that lie on the hut floor and are pushed into the fire as it needs more juice). Some villages now have generators, but many of the small ones don't. When the sun goes down, the people may burn small lanterns, but mostly the village is just dark. There are no cars, only dugout canoes (ulus) which many islanders row long distances to collect water when their island has no supply of agua dulce. More often than not, this task falls to the women. The village "streets" are sand; most everybody is either barefoot or in busted up plastic sandals. Little kids run around blissfully butt-naked. There doesn't seem to be a traditional dress for the men (ratty shorts and T-shirts are the norm), but the women make up for it with theirs. Kuna Yala is home to the mola, a hand-stitched, reverse-appliqué creation with embroidery and intricate designs that the women make into their blouses--and also peddle with intrepid persistence to cruisers like us. In many places, the anchor hasn't even hit the bottom before ulus full of mola-selling Kunas are bumping the side of the boat, waving their molas to get you to look at their offerings first.

The reality is that molas are now the main source of revenue for the Kunas. Until only recently their economy was based on coconuts, which served as both currency and their chief source of income. Coconuts remain an important commodity, so much so that coconut care-taker families are assigned to many of the uninhabited islands to tend the coconut trees and protect their droppings. But the market for coconuts is down, and even though the Colombian traders still ply the San Blas for them, the Kuna women and their molas have replaced coconuts as the income generators. Beyond what they can earn from molas, the Kuna live as close to a subsistence life as any indigenous people anywhere, eating primarily fish, bananas and plantains, rice, and coconuts. Sometimes the men hunt in the mainland coastal jungle and if they can bag a wild pig or a deer they may feast on meat for a few days.

The San Blas islands all have Kuna names representing animals or plants. Our San Blas landfall was at Isla Pino--Tubpak in Kuna because the island's big lopsided hill looks like a whale on its side--well down the chain. We made the overnight passage from the Rosario Islands near Cartagena with Ithaka and had picked a perfect weather window to do it: for a change we managed a lovely, uneventful 24-hour passage. After motoring the first few hours in no wind, the breeze picked up and we were rewarded with a brisk but comfortable sail the rest of the way. We celebrated crossing into single-digit latitudes. The only breath-catching moment came when Ithaka collided with an enormous log. At night this kind of floating debris is hopelessly invisible and a random menace we all fear. Except for scaring the hell out of them and jarring their depth-sounder from its socket in the hull, there was no damage, and we pressed on, hoping the villain was a lone operator and not a member of a pack.

Isla Pino was a perfect introduction to the San Blas: a small, traditional village where the women weren't allowed to row out to the boats to sell molas. (Apparently not all of them knew about that rule, however, as one hopeful early visitor did row out to see us.) Once in the village we were befriended by a worldly young Kuna named David (he'd been to Panama City), who thought he spoke English, and his little 10 year old "assistant," Wilson. Wilson was adorable, David kind of an entrepreneurial weasel. He escorted us to see the sailah (chief), who was swinging lazily in his hammock while his wife tended a pot over the fire. The sailah extracted a $2/head visitor tax from us and then David led us around the small, tidy village (total population about 300) where we got our first glimpse of Kuna life: the pervasive smoky smell from the cookfire logs; the women all in traditional dress, many sitting outside their huts working on molas; little kids running around, shy but curious, sticking their heads out from behind doors or their mothers calling "Merki, Merki!" (American!). Many Kuna are wary of cameras, especially the women, so we asked permission to take pictures and snapped judiciously in this National Geographic-like setting, careful not to aim directly at people. One family, however, eagerly asked that we take a picture of their baby, whom they spiffed up and nestled in a plastic tub for the shot. When we returned with a printed picture they were thrilled and gave us three coconuts as a gift. Delivering this one and a couple of others opened a flood gate of requests. We became the official island photographers for several days, taxing our small color printer cartridge and our supply of photo paper. But it was a great opportunity to get people pictures we otherwise never would have been able to pull off--from little kids to two of the sailahs, one of whom put on a white shirt, a funny old wide tie not much longer than a bib, and an old "pork-pie" hat that made him look like a Chicago gangster. He stared stone-faced into the camera for this portrait, but a few minutes later when we took another of him with his two little granddaughters in frilly pink dresses (who turned out to be Wilson's sisters) his stern stare melted into a gentle, warm smile that we've come to see on most of the Kuna men we've met.

We managed to lose David and find Horacio, a charming Kuna gentleman we'd been advised by other cruisers to look up. Horacio was about 60, a slight man with a shy crooked smile that we saw more of as the week went by. His wife was a plump, jovial woman with a ready smile, eager to sell molas that, unfortunately, she just wasn't very good at making. They had an ancient Mercedes treadle sewing machine that hadn't worked in months--maybe years--that Horacio asked Jim if he could fix. Jim agreed to take a look and they carried it from the dark hut out into the sun, sticking a board under one foot to level it in the sand. The problem was clear (we thought): instead of a belt on the wheel there was a ratty piece of twine. We were sure that was it, so, lacking a belt, we fashioned one from a spare piece of shock cord: Jim cut and burned the ends, I sewed them together. But that was only problem #1. Among other things, the tension fittings were a garbled mess. We took them all apart, realigned the pieces in the right order (at least in the order they go on our machine), re-shaped the tangled little piece of wire the thread loops through, and reassembled the whole thing. I couldn't make the treadle peddles work together to give it a test run, so called in Mrs. Martines to try it out. She sat down on the little tree-trunk stool, positioned her bare feet on the peddles, and pumped. It purred. She beamed.

Selling molas was a community event at Isla Pino. Horacio had advised us not to buy them at individual homes as it created too much "envy," he said. (Never mind that later in the week Mrs. Martines waved us into their hut to sell us a mola.) Instead, word went out through the village for all the women to bring their molas to the Congresso (meeting house) where they spread them in the sand in the communal area outside the big Congresso hut. The whole village turned out; there were molas everywhere. Dozens of them laid on the ground, all on display for the four of us. The pressure and competition were fierce. The women watched our every move, every pause to inspect someone's mola. While on the one hand they were eager to sell and the prices were somewhat negotiable, on the other, we sensed a subtle form of price fixing as nobody wanted to come down too far in front of her neighbors. In the end, the island was richer for our visit.

From Isla Pino we headed SE to another Kuna village on Isla Caledonia (Kanirdup in Kuna). Somewhat larger (population about 1000), this was also a very traditional village where we saw our first albino Kunas. (There is considerable intermarriage among these tightly tribal people, the result being the world's highest incidence of albinism. The Kuna revere their albino offspring and call them "moon children.") In this village there was no taboo against selling molas at the boats and we were regularly visited by women or whole families who rowed out to see us in their tippy, leaky ulus. We were amazed to see little kids, as young as 5 or 6 years old, often rowing around in an ulu, one or two skillfully maneuvering the traditional wood paddles used as both oars and rudder, another with the endless task of bailing. Usually the bailer is a coconut shell or a calabash, tho sometimes a plastic bottle. In one village where Peace Corps distributed hard hats for a construction project the villagers suddenly had a supply of high-volume bailers. Things like life jackets and protective head gear just aren't part of the Kuna world.

At Caledonia we weren't far from the Colombian border and had our first experience with the Colombian traders that port-hop through the San Blas selling a few vegetables and basic dry goods and filling their holds with coconuts for processing in Colombia. Bernadette and I had been on a mola mission in the village and saw the trading boat come in. The pier was abuzz with villagers, as these boats are the source of just about everything that comes to the island, including and especially plantains. The ship's hold was deep with them and an enormous pile already had been moved to the dock where the women were picking through them. As soon as all the plantains were gone, they'd be replaced by coconuts for the trip back. We were after fresh vegetables and were welcomed aboard to pick through the tomatoes, carrots, green peppers, onions, cucumbers--enough stuff to keep us going till the next boat came in. We quickly learned that if you see it, buy it; the next boat may not have it; this was the only source of fresh stuff for quite a while.

All the villages have tiendas (stores), but most are little more than small dark rooms with a few diminutive items on a couple of bare wood shelves. They look like the "dry goods stores" in old westerns, where there's a counter along the length of the store and all the items for sale are behind it. The stock is pretty minimal: a few cans of sardines and tuna, tiny jars of Miracle Whip (?!), cans of Campbell's Pork & Beans, maybe a tiny can or two of fruit cocktail and tomato paste, sometimes a few bags of dried beans and lentils, and always rice. There are usually a few "personal items," some laundry soap, and almost always very small bottles of Clorox. Initially impressed that they were so concerned with getting their whites white, we were dismayed to learn that Clorox was more likely used in fishing than laundering. Some of the bigger villages have more extensive tiendas, but Super Safeway they aren't. Rarely is there any fresh produce, except maybe some onions and garlic, so we learned to keep careful watch for the Colombian traders, calling "Hay verduras?" (do you have vegetables?) as we approached them in the dinghy.

Already as far down in the San Blas as you can go at Isla Caledonia, we turned around and headed back north and west from there, moving when the weather allowed the necessary eyeball navigation through the reefs and picking our stops based on how far we felt like going on any one day. In Mamitupu, another traditional Kuna village, we were warmly welcomed by Pablo, a truly worldly Kuna who spoke perfect English. He had mastered our tongue living 7 years in England where he and his fair-haired English bride had fled after he was banished from the village for marrying outside the tribe. From Pablo we learned not only his interesting story--he eventually returned to Mamitupu and took a Kuna bride--but also much about other Kuna traditions:

- When Kuna girls reach puberty there is an elaborate "chicha" ceremony, at which the girl's hair is cut by a special woman and she's given her name by a medicine man. Up until then, she's known simply by a nickname. Chicha is a powerful brew made of fermented corn, sugar cane, and cocoa, a great deal of which is consumed during the 4-day puberty ceremony.

- Kuna marriages are arranged, and until recently, they could only marry someone in their own village (hence the high rate of albinism). After the marriage, the couple goes to live with the bride's mother's family. (Pablo said he didn't think he'd be banished if he were to marry an outsider now, but village life is still fairly strictly regulated.)

- Many of the best mola makers are gay men. Some say that if the family has no girls to learn the craft they teach one of the boys. Whatever the reason, there are many gay/transvestite Kunas who make exceptional molas.

- Each village has elected sailahs (chiefs) who wield considerable power over village life. Kunas can't travel between islands without permission and they can be fined if they don't attend the regular village-wide "congresso" meetings. One evening Pablo told us he was going hunting in the mainland jungle for wild boar. We asked him about the congresso meeting that night, but he had permission from the sailah not to attend.

Mamitupu has an abundant supply of fresh water so this was the place to do laundry. We'd been pretty lucky up till now, always finding laundromats or laundry-doers, but in the San Blas we were on our own. Doing king-size sheets and bath towels in a bucket is one of cruising's less appealing features, but out here there's little choice. So the four of us piled our laundry into the dinghies and took it to Pablo's shower hut where there was water and half an old ulu (a Kuna washing machine) mounted on sticks at about hip level to save your back while kneading your dirty duds. We sorted and scrubbed and rinsed and wrung, drawing a crowd of curious children who watched and giggled as the crazy gringos --and gringo MEN at that!--did their wash. My kingdom for a Maytag!

We continued to poke our way up the island chain, stopping next at Isla Playon Chico in late February where we fortuitously landed at the start of the week-long celebration and reenactment of the 1925 Kuna revolution against the Panamanian government. This was the definition of community theater: the streets were the stage and anybody who wanted a part had one. There was ceremony, music, dancing, singing, shooting, yelling, whooping, weeping, conniving, creeping, crawling, prowling, parading, marching, hanging, burning, disemboweling, and tossing bodies into the sea. Large bands of red-clad, black-face, barefoot, stick-toting 6 year olds diligently policed the streets for days patrolling for bad guys. On our first day there we were all ceremoniously "arrested" for wearing shorts and hauled off to the police hut where they told us the story of the revolution, its events and significance, and fined us an amount of our choosing (to help support the festivities). One of the ladies made us a Kuna Yala flag which, unfortunately, looks a lot like a swastika, but the Kunas selected this symbol before Hitler got his hands on it and gave it such a bad name.

The celebration over and the weather good, we headed NW once again, stopping at a couple more villages along the way and ending up finally in the area of the San Blas where most cruisers hang out. One of the favorite anchorages is known as "the swimming pool," an aptly named spot with crystal clear, shallow aqua water where you can watch stuff swimming around the boat under you. We've seen rays, barracuda, schools of jacks, and lately some friends reported nosy nurse sharks messing around with their fishing lines. Our favorite spot in the San Blas has turned out to be the Lemon Cays, a cluster of about 8 little islands covered with palm trees and ringed with white sand and fabulous reefs for snorkeling. There are no villages on these islands, only caretaker families whom we've gotten to know in our many stops here. Their lives are profoundly simple: they have no electricity, no plumbing. The women make molas, cook, row where they have to to get water, and tend the children. The men fish and tend the coconuts. We are visited almost daily by ulus with fishermen returning from the reef. They'll have lobster or crab (the biggest we've ever seen), an assortment of large and small fish, maybe some octopus. If we haven't caught any of our own (so far it's Fish 10, Jim 0 on the spearfishing), we'll buy or trade for something. Yesterday we traded a spear tip for a big lobster; another time we traded a gallon of outboard gas for a big crab (when I say "big" I mean a crab that will feed the two of us!). The grocery store meat we had stuffed in our small freezer remains largely untouched.

Living out here in this blissful isolation forced us to provision well and store carefully. While some fresh produce can be had, you never know where or when. If we see it, we buy it, and then find a way to store it in our small cramped refrigerator, in a hammock in the cockpit, or in the guest room (which out here is also the pantry). We've become quite expert at eking out a long life from a head of lettuce or bag of carrots. Everything gets washed in a dilute bleach solution and dried in the sun. When we left Cartagena in January we did a huge shop at the local produce market where we tried to stock up for several months. The stuff was so cheap that if you lost some it was no big deal. But we had batches of tomatoes and oranges and peppers and cucumbers and eggplants bobbing in bleach for hours. I learned to wrap the green tomatoes and all the citrus in foil to preserve them without refrigeration. I even coded the tomatoes 1, 2, or 3 based on how close they were to being ripe and which to use first. Sometimes I mis-guessed... We don't refrigerate eggs and they keep just fine for a long time as long as we turn them every couple of days. With the supply so limited, we are parsimonious and careful in the use of precious fresh stuff: I've cut little brown bits off lettuce I long since would have pitched in the past. And when the lettuce runs out, there's always cabbage. It lasts forever.

After 2 ½ months out here it was time to hit a grocery store and we still hadn't checked into Panama, so we set off for Colon. This city, with a well-deserved reputation as a dive (and so dangerous that even the locals are always telling us to be careful), is the Caribbean gateway to the Panama Canal. We scurried around accomplishing official paperwork, doing the laundry in real Maytags, refilling the wine cellar, prowling the aisles of the well-stocked grocery stores, fixing boat stuff, being tourists at the Gatun Locks of the Canal, making a run to the big city (Panama), and generally preparing to get back out to the San Blas as soon as we could. On the day we were casting the lines to leave, we heard on the morning radio net that another boat had just come from the Rio Chagres, that famous jungle river that was dammed and diverted in the building of the Panama Canal. We had intended to spend some time in this favorite cruiser spot, but when the war started the Canal Authority threw all the cruisers out for "security reasons." Apparently they thought the dam was vulnerable to terrorists. But this report on the cruiser net caught our attention, so as we exited the breakwater at Colon we turned left for the 7 mile trip to the Rio rather than right to return to the San Blas. We were traveling with our friends on The W.C. Fields and we must have been the only two boats who heard that the river was "open" again, because we were the only ones up there. It's a five-mile windy stretch of river in the middle of the jungle. We saw tropical birds, monkeys leaping and yelling in the trees, a sloth hanging upside down munching on a tree, a huge crocodile ghosting along the bank, lizards, and crabs, and all kinds of other critters. This area was formerly used by the military for jungle survival training and there are trails all through the hills; one we walked was left from the days of the French attempt at burrowing a canal through the isthmus.

After our 10-day diversion to the Rio, it been a month since we'd left the San Blas and we were ready to return. When we did, around the first of May, the rainy season arrived with us, right on time. For the first 2 weeks we were back we never saw the sun and wondered what we'd gotten ourselves into. An old Kuna assured us it would get better, and indeed it did, but now we only see the sun about half-time as compared to the full-time duty it did earlier in the year. The San Blas rainy season is also notorious for its thunder storms. This, too, is a well-deserved reputation: we've never seen anything like the lightning out here. Maybe it's just that it has no competition in the sky, but it looks and feels much more intense than any we've ever experienced. Like the Scarecrow who declares the only thing he fears is fire, we feel the same about lightning. There is nothing quite as vulnerable and helpless as a sailboat in a wide open anchorage in a violent thunderstorm. We've done just about everything we can to protect the boat: Jim installed a little fuzzy gizmo on the mast that's supposed to dissipate static charges so they don't build up; we hang a zinc over the side into the water, clamped to a high shroud to ground the boat and provide an electrical path other than us; and when we hear the rumbling begin, we put a hand-held radio and GPS into the oven so that if we take a hit and all the other electronics are fried, at least we can call someone and get somewhere. Then we just sit and watch and wait. One night the show was so intense, the lightning continuous and the rumble of the thunder so basso-profundo that we just laid in bed holding hands, feeling the hull shudder with each crash. We probably should have been singing "These are a few of my favorite things..." A couple of our friends have been hit, or taken near hits. So far we've been lucky and will just continue to cringe away and hide stuff in the oven as they roll through every couple of days.

The intense rain inspired us finally to hook up the water catchment system we've had since Trinidad. When we had our awning built there they put fittings thru the fabric that we can attach hoses for catching water and sending it to the tanks. Even though we have a watermaker, out here it's dumb to run it. The rain is so heavy sometimes that we can fill a 100 gallon tank in barely an hour. The buckets are all strategically placed as well, and when they're full, like they are now, I have no excuse not to do laundry (fortunately we don't generate much). In between these drenching torrents we are treated to days of sun where we dry things out, scurry back to the reefs to snorkel, move from one island to an another, burn our trash on a deserted beach, polish the stainless, varnish, visit our Kuna friends, or just hang out and refresh our tans. Needless to say, we love it here. It's hard to do justice with these inadequate words to describe the pristine beauty of these islands, the tranquility, the isolation, the warm and interesting Kuna culture...

We came to this enchanted isolation after an equally enchanting 3 ½ months in highly civilized Cartagena, a city that has its own well-deserved reputation as the jewel of the Spanish Main. Whatever the problems in the rest of Colombia, Cartagena is also an isolated gem. Not once did we feel in danger there. The people are warm and bend-over-backwards friendly. The restaurants are abundant, good, and cheap. The old city oozes historical charm. Old Spanish fortresses are a dominating presence. Shops abound with ethnic treasures...and emeralds. With a grocery store around the corner we didn't have to cut brown bits off the lettuce; the butcher a block in the other direction had fillet at $2.50 a pound (but it hardly mattered as we ate out so much ... you couldn't afford not to!). A 5-star hotel in the old city, a former convent, welcomed cruisers to their roof pool with a drop dead view of Cartagena Bay and the rooftops of the city. At Christmas the town transformed into a holiday fairy land: the entire wall around the old city, every one of its little watch towers, was carefully outlined with tiny white lights. Suspended across every street were rows and rows of lighted lanterns, stars, snowflakes, bells. Big butterflies, yellow in daylight and alight at night, hung from the old majestic trees in the old city's plazas. What's not to like? We hated to leave, but then you already know what we had ahead of us...

Now we're feeling the same way about the San Blas: our time here is running out and we hate to leave. We tell ourselves that there are more wonderful places ahead, but this one's going to be hard to beat. We'll be back in the States in September for a few weeks, so if anyone wants to hear more about these special places (or our run-in with the pirates last year) or see our thousand-or-so pictures (!), let us know. I've only scratched the surface in these few short pages. But short it must remain because this is our first time sending something this long over winlink and I don't want to blow out the radio.

Right now we're off to watch bread bake in the maiden lighting of a new wood-fired brick oven a cruiser built for one of the Kuna families. And people wonder what we do all day...?

Everyone enjoy what's left of your summer. For all of you in the D.C. area, I hope the rain stops! Hasta luego.

The Inmates

We left Cartagena in mid-January after 3 ½ glorious months there. On the one hand we hated to leave its comforts and charms, but on the other, we were ready to be out of a marina swinging on the hook in the fabled blue-water, palm-infested, white-sand islands of the San Blas. In Cartagena one of our slip-mates was Ithaka, with Bernadette and Douglas aboard, she the former editor of Cruising World magazine. They were headed back to the San Blas at the same time so we ended up traveling with them for about 2 months--an immeasurable cruising treat for us.

For most people, Panama is known for two things: the Canal and our famous spat with its notorious thug, Noriega, back in the late 80s. The San Blas should be added to the list! This jewel chain of 400 islands--many small enough to leap across--and coral reefs stretches about 130 miles along Panama's Caribbean coast. The vast majority of the islands are uninhabited, and on those that are (habited, that is) live the Kuna Indians, an indigenous tribe of about 70,000. They're a stout (second only to the pygmies in shortness of stature), tenaciously traditional bunch, always described in the guide books as "fiercely independent." In 1925 they staged a sly rebellion against the Panamanian government--which they celebrate and reenact every year with faithfully rendered street theater--and became the "autonomous region" of the San Blas (Kuna Yala in their language).

This is a place time just hasn't paid much attention to. The people still live in thatched huts, one for sleeping (in hammocks) and another for cooking (over wood fires kept alight with 4 large logs that lie on the hut floor and are pushed into the fire as it needs more juice). Some villages now have generators, but many of the small ones don't. When the sun goes down, the people may burn small lanterns, but mostly the village is just dark. There are no cars, only dugout canoes (ulus) which many islanders row long distances to collect water when their island has no supply of agua dulce. More often than not, this task falls to the women. The village "streets" are sand; most everybody is either barefoot or in busted up plastic sandals. Little kids run around blissfully butt-naked. There doesn't seem to be a traditional dress for the men (ratty shorts and T-shirts are the norm), but the women make up for it with theirs. Kuna Yala is home to the mola, a hand-stitched, reverse-appliqué creation with embroidery and intricate designs that the women make into their blouses--and also peddle with intrepid persistence to cruisers like us. In many places, the anchor hasn't even hit the bottom before ulus full of mola-selling Kunas are bumping the side of the boat, waving their molas to get you to look at their offerings first.

The reality is that molas are now the main source of revenue for the Kunas. Until only recently their economy was based on coconuts, which served as both currency and their chief source of income. Coconuts remain an important commodity, so much so that coconut care-taker families are assigned to many of the uninhabited islands to tend the coconut trees and protect their droppings. But the market for coconuts is down, and even though the Colombian traders still ply the San Blas for them, the Kuna women and their molas have replaced coconuts as the income generators. Beyond what they can earn from molas, the Kuna live as close to a subsistence life as any indigenous people anywhere, eating primarily fish, bananas and plantains, rice, and coconuts. Sometimes the men hunt in the mainland coastal jungle and if they can bag a wild pig or a deer they may feast on meat for a few days.

The San Blas islands all have Kuna names representing animals or plants. Our San Blas landfall was at Isla Pino--Tubpak in Kuna because the island's big lopsided hill looks like a whale on its side--well down the chain. We made the overnight passage from the Rosario Islands near Cartagena with Ithaka and had picked a perfect weather window to do it: for a change we managed a lovely, uneventful 24-hour passage. After motoring the first few hours in no wind, the breeze picked up and we were rewarded with a brisk but comfortable sail the rest of the way. We celebrated crossing into single-digit latitudes. The only breath-catching moment came when Ithaka collided with an enormous log. At night this kind of floating debris is hopelessly invisible and a random menace we all fear. Except for scaring the hell out of them and jarring their depth-sounder from its socket in the hull, there was no damage, and we pressed on, hoping the villain was a lone operator and not a member of a pack.

Isla Pino was a perfect introduction to the San Blas: a small, traditional village where the women weren't allowed to row out to the boats to sell molas. (Apparently not all of them knew about that rule, however, as one hopeful early visitor did row out to see us.) Once in the village we were befriended by a worldly young Kuna named David (he'd been to Panama City), who thought he spoke English, and his little 10 year old "assistant," Wilson. Wilson was adorable, David kind of an entrepreneurial weasel. He escorted us to see the sailah (chief), who was swinging lazily in his hammock while his wife tended a pot over the fire. The sailah extracted a $2/head visitor tax from us and then David led us around the small, tidy village (total population about 300) where we got our first glimpse of Kuna life: the pervasive smoky smell from the cookfire logs; the women all in traditional dress, many sitting outside their huts working on molas; little kids running around, shy but curious, sticking their heads out from behind doors or their mothers calling "Merki, Merki!" (American!). Many Kuna are wary of cameras, especially the women, so we asked permission to take pictures and snapped judiciously in this National Geographic-like setting, careful not to aim directly at people. One family, however, eagerly asked that we take a picture of their baby, whom they spiffed up and nestled in a plastic tub for the shot. When we returned with a printed picture they were thrilled and gave us three coconuts as a gift. Delivering this one and a couple of others opened a flood gate of requests. We became the official island photographers for several days, taxing our small color printer cartridge and our supply of photo paper. But it was a great opportunity to get people pictures we otherwise never would have been able to pull off--from little kids to two of the sailahs, one of whom put on a white shirt, a funny old wide tie not much longer than a bib, and an old "pork-pie" hat that made him look like a Chicago gangster. He stared stone-faced into the camera for this portrait, but a few minutes later when we took another of him with his two little granddaughters in frilly pink dresses (who turned out to be Wilson's sisters) his stern stare melted into a gentle, warm smile that we've come to see on most of the Kuna men we've met.

We managed to lose David and find Horacio, a charming Kuna gentleman we'd been advised by other cruisers to look up. Horacio was about 60, a slight man with a shy crooked smile that we saw more of as the week went by. His wife was a plump, jovial woman with a ready smile, eager to sell molas that, unfortunately, she just wasn't very good at making. They had an ancient Mercedes treadle sewing machine that hadn't worked in months--maybe years--that Horacio asked Jim if he could fix. Jim agreed to take a look and they carried it from the dark hut out into the sun, sticking a board under one foot to level it in the sand. The problem was clear (we thought): instead of a belt on the wheel there was a ratty piece of twine. We were sure that was it, so, lacking a belt, we fashioned one from a spare piece of shock cord: Jim cut and burned the ends, I sewed them together. But that was only problem #1. Among other things, the tension fittings were a garbled mess. We took them all apart, realigned the pieces in the right order (at least in the order they go on our machine), re-shaped the tangled little piece of wire the thread loops through, and reassembled the whole thing. I couldn't make the treadle peddles work together to give it a test run, so called in Mrs. Martines to try it out. She sat down on the little tree-trunk stool, positioned her bare feet on the peddles, and pumped. It purred. She beamed.

Selling molas was a community event at Isla Pino. Horacio had advised us not to buy them at individual homes as it created too much "envy," he said. (Never mind that later in the week Mrs. Martines waved us into their hut to sell us a mola.) Instead, word went out through the village for all the women to bring their molas to the Congresso (meeting house) where they spread them in the sand in the communal area outside the big Congresso hut. The whole village turned out; there were molas everywhere. Dozens of them laid on the ground, all on display for the four of us. The pressure and competition were fierce. The women watched our every move, every pause to inspect someone's mola. While on the one hand they were eager to sell and the prices were somewhat negotiable, on the other, we sensed a subtle form of price fixing as nobody wanted to come down too far in front of her neighbors. In the end, the island was richer for our visit.

From Isla Pino we headed SE to another Kuna village on Isla Caledonia (Kanirdup in Kuna). Somewhat larger (population about 1000), this was also a very traditional village where we saw our first albino Kunas. (There is considerable intermarriage among these tightly tribal people, the result being the world's highest incidence of albinism. The Kuna revere their albino offspring and call them "moon children.") In this village there was no taboo against selling molas at the boats and we were regularly visited by women or whole families who rowed out to see us in their tippy, leaky ulus. We were amazed to see little kids, as young as 5 or 6 years old, often rowing around in an ulu, one or two skillfully maneuvering the traditional wood paddles used as both oars and rudder, another with the endless task of bailing. Usually the bailer is a coconut shell or a calabash, tho sometimes a plastic bottle. In one village where Peace Corps distributed hard hats for a construction project the villagers suddenly had a supply of high-volume bailers. Things like life jackets and protective head gear just aren't part of the Kuna world.

At Caledonia we weren't far from the Colombian border and had our first experience with the Colombian traders that port-hop through the San Blas selling a few vegetables and basic dry goods and filling their holds with coconuts for processing in Colombia. Bernadette and I had been on a mola mission in the village and saw the trading boat come in. The pier was abuzz with villagers, as these boats are the source of just about everything that comes to the island, including and especially plantains. The ship's hold was deep with them and an enormous pile already had been moved to the dock where the women were picking through them. As soon as all the plantains were gone, they'd be replaced by coconuts for the trip back. We were after fresh vegetables and were welcomed aboard to pick through the tomatoes, carrots, green peppers, onions, cucumbers--enough stuff to keep us going till the next boat came in. We quickly learned that if you see it, buy it; the next boat may not have it; this was the only source of fresh stuff for quite a while.

All the villages have tiendas (stores), but most are little more than small dark rooms with a few diminutive items on a couple of bare wood shelves. They look like the "dry goods stores" in old westerns, where there's a counter along the length of the store and all the items for sale are behind it. The stock is pretty minimal: a few cans of sardines and tuna, tiny jars of Miracle Whip (?!), cans of Campbell's Pork & Beans, maybe a tiny can or two of fruit cocktail and tomato paste, sometimes a few bags of dried beans and lentils, and always rice. There are usually a few "personal items," some laundry soap, and almost always very small bottles of Clorox. Initially impressed that they were so concerned with getting their whites white, we were dismayed to learn that Clorox was more likely used in fishing than laundering. Some of the bigger villages have more extensive tiendas, but Super Safeway they aren't. Rarely is there any fresh produce, except maybe some onions and garlic, so we learned to keep careful watch for the Colombian traders, calling "Hay verduras?" (do you have vegetables?) as we approached them in the dinghy.

Already as far down in the San Blas as you can go at Isla Caledonia, we turned around and headed back north and west from there, moving when the weather allowed the necessary eyeball navigation through the reefs and picking our stops based on how far we felt like going on any one day. In Mamitupu, another traditional Kuna village, we were warmly welcomed by Pablo, a truly worldly Kuna who spoke perfect English. He had mastered our tongue living 7 years in England where he and his fair-haired English bride had fled after he was banished from the village for marrying outside the tribe. From Pablo we learned not only his interesting story--he eventually returned to Mamitupu and took a Kuna bride--but also much about other Kuna traditions:

- When Kuna girls reach puberty there is an elaborate "chicha" ceremony, at which the girl's hair is cut by a special woman and she's given her name by a medicine man. Up until then, she's known simply by a nickname. Chicha is a powerful brew made of fermented corn, sugar cane, and cocoa, a great deal of which is consumed during the 4-day puberty ceremony.

- Kuna marriages are arranged, and until recently, they could only marry someone in their own village (hence the high rate of albinism). After the marriage, the couple goes to live with the bride's mother's family. (Pablo said he didn't think he'd be banished if he were to marry an outsider now, but village life is still fairly strictly regulated.)

- Many of the best mola makers are gay men. Some say that if the family has no girls to learn the craft they teach one of the boys. Whatever the reason, there are many gay/transvestite Kunas who make exceptional molas.

- Each village has elected sailahs (chiefs) who wield considerable power over village life. Kunas can't travel between islands without permission and they can be fined if they don't attend the regular village-wide "congresso" meetings. One evening Pablo told us he was going hunting in the mainland jungle for wild boar. We asked him about the congresso meeting that night, but he had permission from the sailah not to attend.

Mamitupu has an abundant supply of fresh water so this was the place to do laundry. We'd been pretty lucky up till now, always finding laundromats or laundry-doers, but in the San Blas we were on our own. Doing king-size sheets and bath towels in a bucket is one of cruising's less appealing features, but out here there's little choice. So the four of us piled our laundry into the dinghies and took it to Pablo's shower hut where there was water and half an old ulu (a Kuna washing machine) mounted on sticks at about hip level to save your back while kneading your dirty duds. We sorted and scrubbed and rinsed and wrung, drawing a crowd of curious children who watched and giggled as the crazy gringos --and gringo MEN at that!--did their wash. My kingdom for a Maytag!

We continued to poke our way up the island chain, stopping next at Isla Playon Chico in late February where we fortuitously landed at the start of the week-long celebration and reenactment of the 1925 Kuna revolution against the Panamanian government. This was the definition of community theater: the streets were the stage and anybody who wanted a part had one. There was ceremony, music, dancing, singing, shooting, yelling, whooping, weeping, conniving, creeping, crawling, prowling, parading, marching, hanging, burning, disemboweling, and tossing bodies into the sea. Large bands of red-clad, black-face, barefoot, stick-toting 6 year olds diligently policed the streets for days patrolling for bad guys. On our first day there we were all ceremoniously "arrested" for wearing shorts and hauled off to the police hut where they told us the story of the revolution, its events and significance, and fined us an amount of our choosing (to help support the festivities). One of the ladies made us a Kuna Yala flag which, unfortunately, looks a lot like a swastika, but the Kunas selected this symbol before Hitler got his hands on it and gave it such a bad name.

The celebration over and the weather good, we headed NW once again, stopping at a couple more villages along the way and ending up finally in the area of the San Blas where most cruisers hang out. One of the favorite anchorages is known as "the swimming pool," an aptly named spot with crystal clear, shallow aqua water where you can watch stuff swimming around the boat under you. We've seen rays, barracuda, schools of jacks, and lately some friends reported nosy nurse sharks messing around with their fishing lines. Our favorite spot in the San Blas has turned out to be the Lemon Cays, a cluster of about 8 little islands covered with palm trees and ringed with white sand and fabulous reefs for snorkeling. There are no villages on these islands, only caretaker families whom we've gotten to know in our many stops here. Their lives are profoundly simple: they have no electricity, no plumbing. The women make molas, cook, row where they have to to get water, and tend the children. The men fish and tend the coconuts. We are visited almost daily by ulus with fishermen returning from the reef. They'll have lobster or crab (the biggest we've ever seen), an assortment of large and small fish, maybe some octopus. If we haven't caught any of our own (so far it's Fish 10, Jim 0 on the spearfishing), we'll buy or trade for something. Yesterday we traded a spear tip for a big lobster; another time we traded a gallon of outboard gas for a big crab (when I say "big" I mean a crab that will feed the two of us!). The grocery store meat we had stuffed in our small freezer remains largely untouched.

Living out here in this blissful isolation forced us to provision well and store carefully. While some fresh produce can be had, you never know where or when. If we see it, we buy it, and then find a way to store it in our small cramped refrigerator, in a hammock in the cockpit, or in the guest room (which out here is also the pantry). We've become quite expert at eking out a long life from a head of lettuce or bag of carrots. Everything gets washed in a dilute bleach solution and dried in the sun. When we left Cartagena in January we did a huge shop at the local produce market where we tried to stock up for several months. The stuff was so cheap that if you lost some it was no big deal. But we had batches of tomatoes and oranges and peppers and cucumbers and eggplants bobbing in bleach for hours. I learned to wrap the green tomatoes and all the citrus in foil to preserve them without refrigeration. I even coded the tomatoes 1, 2, or 3 based on how close they were to being ripe and which to use first. Sometimes I mis-guessed... We don't refrigerate eggs and they keep just fine for a long time as long as we turn them every couple of days. With the supply so limited, we are parsimonious and careful in the use of precious fresh stuff: I've cut little brown bits off lettuce I long since would have pitched in the past. And when the lettuce runs out, there's always cabbage. It lasts forever.

After 2 ½ months out here it was time to hit a grocery store and we still hadn't checked into Panama, so we set off for Colon. This city, with a well-deserved reputation as a dive (and so dangerous that even the locals are always telling us to be careful), is the Caribbean gateway to the Panama Canal. We scurried around accomplishing official paperwork, doing the laundry in real Maytags, refilling the wine cellar, prowling the aisles of the well-stocked grocery stores, fixing boat stuff, being tourists at the Gatun Locks of the Canal, making a run to the big city (Panama), and generally preparing to get back out to the San Blas as soon as we could. On the day we were casting the lines to leave, we heard on the morning radio net that another boat had just come from the Rio Chagres, that famous jungle river that was dammed and diverted in the building of the Panama Canal. We had intended to spend some time in this favorite cruiser spot, but when the war started the Canal Authority threw all the cruisers out for "security reasons." Apparently they thought the dam was vulnerable to terrorists. But this report on the cruiser net caught our attention, so as we exited the breakwater at Colon we turned left for the 7 mile trip to the Rio rather than right to return to the San Blas. We were traveling with our friends on The W.C. Fields and we must have been the only two boats who heard that the river was "open" again, because we were the only ones up there. It's a five-mile windy stretch of river in the middle of the jungle. We saw tropical birds, monkeys leaping and yelling in the trees, a sloth hanging upside down munching on a tree, a huge crocodile ghosting along the bank, lizards, and crabs, and all kinds of other critters. This area was formerly used by the military for jungle survival training and there are trails all through the hills; one we walked was left from the days of the French attempt at burrowing a canal through the isthmus.

After our 10-day diversion to the Rio, it been a month since we'd left the San Blas and we were ready to return. When we did, around the first of May, the rainy season arrived with us, right on time. For the first 2 weeks we were back we never saw the sun and wondered what we'd gotten ourselves into. An old Kuna assured us it would get better, and indeed it did, but now we only see the sun about half-time as compared to the full-time duty it did earlier in the year. The San Blas rainy season is also notorious for its thunder storms. This, too, is a well-deserved reputation: we've never seen anything like the lightning out here. Maybe it's just that it has no competition in the sky, but it looks and feels much more intense than any we've ever experienced. Like the Scarecrow who declares the only thing he fears is fire, we feel the same about lightning. There is nothing quite as vulnerable and helpless as a sailboat in a wide open anchorage in a violent thunderstorm. We've done just about everything we can to protect the boat: Jim installed a little fuzzy gizmo on the mast that's supposed to dissipate static charges so they don't build up; we hang a zinc over the side into the water, clamped to a high shroud to ground the boat and provide an electrical path other than us; and when we hear the rumbling begin, we put a hand-held radio and GPS into the oven so that if we take a hit and all the other electronics are fried, at least we can call someone and get somewhere. Then we just sit and watch and wait. One night the show was so intense, the lightning continuous and the rumble of the thunder so basso-profundo that we just laid in bed holding hands, feeling the hull shudder with each crash. We probably should have been singing "These are a few of my favorite things..." A couple of our friends have been hit, or taken near hits. So far we've been lucky and will just continue to cringe away and hide stuff in the oven as they roll through every couple of days.

The intense rain inspired us finally to hook up the water catchment system we've had since Trinidad. When we had our awning built there they put fittings thru the fabric that we can attach hoses for catching water and sending it to the tanks. Even though we have a watermaker, out here it's dumb to run it. The rain is so heavy sometimes that we can fill a 100 gallon tank in barely an hour. The buckets are all strategically placed as well, and when they're full, like they are now, I have no excuse not to do laundry (fortunately we don't generate much). In between these drenching torrents we are treated to days of sun where we dry things out, scurry back to the reefs to snorkel, move from one island to an another, burn our trash on a deserted beach, polish the stainless, varnish, visit our Kuna friends, or just hang out and refresh our tans. Needless to say, we love it here. It's hard to do justice with these inadequate words to describe the pristine beauty of these islands, the tranquility, the isolation, the warm and interesting Kuna culture...

We came to this enchanted isolation after an equally enchanting 3 ½ months in highly civilized Cartagena, a city that has its own well-deserved reputation as the jewel of the Spanish Main. Whatever the problems in the rest of Colombia, Cartagena is also an isolated gem. Not once did we feel in danger there. The people are warm and bend-over-backwards friendly. The restaurants are abundant, good, and cheap. The old city oozes historical charm. Old Spanish fortresses are a dominating presence. Shops abound with ethnic treasures...and emeralds. With a grocery store around the corner we didn't have to cut brown bits off the lettuce; the butcher a block in the other direction had fillet at $2.50 a pound (but it hardly mattered as we ate out so much ... you couldn't afford not to!). A 5-star hotel in the old city, a former convent, welcomed cruisers to their roof pool with a drop dead view of Cartagena Bay and the rooftops of the city. At Christmas the town transformed into a holiday fairy land: the entire wall around the old city, every one of its little watch towers, was carefully outlined with tiny white lights. Suspended across every street were rows and rows of lighted lanterns, stars, snowflakes, bells. Big butterflies, yellow in daylight and alight at night, hung from the old majestic trees in the old city's plazas. What's not to like? We hated to leave, but then you already know what we had ahead of us...

Now we're feeling the same way about the San Blas: our time here is running out and we hate to leave. We tell ourselves that there are more wonderful places ahead, but this one's going to be hard to beat. We'll be back in the States in September for a few weeks, so if anyone wants to hear more about these special places (or our run-in with the pirates last year) or see our thousand-or-so pictures (!), let us know. I've only scratched the surface in these few short pages. But short it must remain because this is our first time sending something this long over winlink and I don't want to blow out the radio.

Right now we're off to watch bread bake in the maiden lighting of a new wood-fired brick oven a cruiser built for one of the Kuna families. And people wonder what we do all day...?

Everyone enjoy what's left of your summer. For all of you in the D.C. area, I hope the rain stops! Hasta luego.

The Inmates

Comments

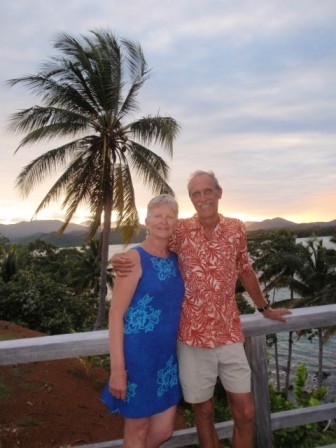

| Vessel Name: | Asylum |

| Vessel Make/Model: | Tayana V-42 Cutter |

| Hailing Port: | Bethesda, MD USA |

| Crew: | Jim & Katie Coolbaugh |

| About: | |

| Extra: | Within Malaysia: 0174209362 (Maxis) WhatsApp +60174209362 |

The Meanderings of Asylum and the Inmates

Who: Jim & Katie Coolbaugh

Port: Bethesda, MD USA

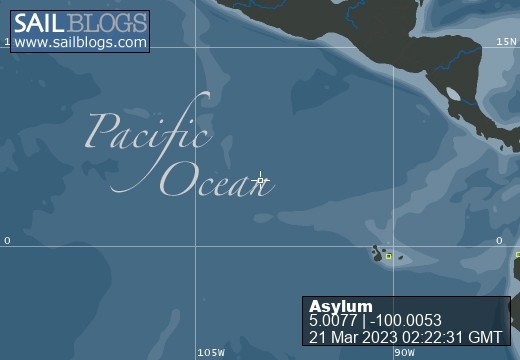

Where in the world is Asylum?

Good links

- Vesper Marine Watchmate AIS

- WinchRite Cordless Winch Handle

- Diving at Tubbataha Reef

- Royal Belau Yacht Club, Palau

- ShipTrack: Our route so far

- Passage Weather

- Interview With a Cruiser Project

- Great diving in the Solomons

- Seven Seas Cruising Association

- Divers Alert Network

- Spectra Watermakers

- Rocna Anchors

.jpeg)